Lonely Leader

- Markets Print Edition

- May 5, 2006

- 0

- 18 minutes read

In March of 2005, Tobacco Reporter’s editor, Taco Tuinstra, visited the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan. His editorial assignment was to prepare a firsthand report from the world’s only smoke-free nation. Taco’s personal goal was to prove wrong his publisher, Noel Morris, who had bet that he wouldn’t dare light a cigarette in the central square of Bhutan’s capital, Thimphu.

Bhutan was the world’s first country to ban tobacco. Will it remain the only one?

By Taco Tuinstra

As Druk Air flight KB127 starts its descent into Paro airport, a passenger in the back of the cabin screams in terror. The gray clouds have abruptly given way to towering mountains left and right—the foothills of the Himalayas—and the pilot must make a series of sharp turns to avoid collision.

I, too, am starting to lose my nerve, but not because of the stomach-turning approach. Druk Air recruits its pilots from the British and American air forces, and surely these flyers are accustomed to more hair-raising maneuvers than landing a civilian jet in a quiet mountain country.

Besides, after nine years at Tobacco Reporter, I take the risks of international air travel in stride. I have survived a Russian airliner carrying more passengers than seats; a lightning strike at 20,000 feet; and, en route to a tobacco auction in Malawi, a chicken (or something else with feathers) flew into the engine of “my” plane, just as the pilot revved up for take-off. Set against such horrors, what is a bit of turbulence?

Rather, the source of my anxiety resides in my carry-on bag—a pack of Krong Thip cigarettes purchased that morning prior to departure from Bangkok. In compliance with Thai law, the pack carries a disturbing picture of what my lungs might look like if I smoke too many of its contents, but that doesn’t worry me, either. I am well aware of the risks of smoking; and besides, to fulfill my personal mission, I have to smoke only one cigarette.

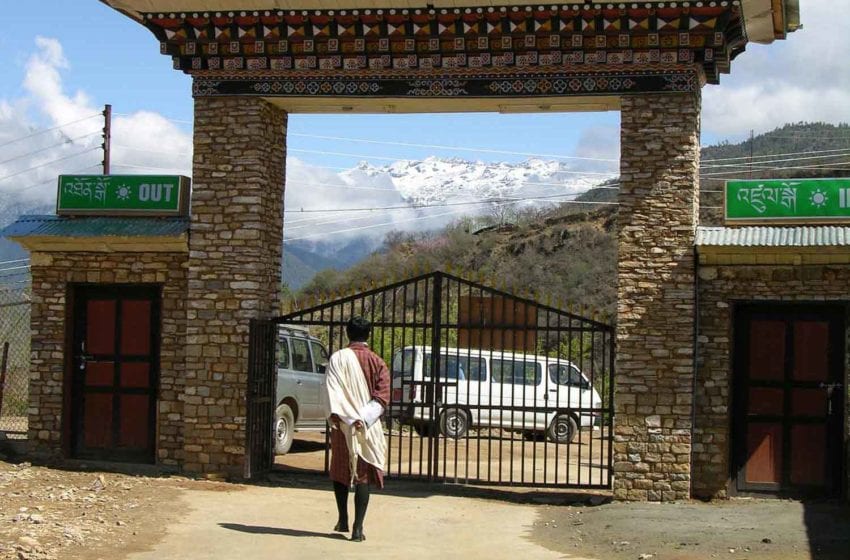

I am nervous because I am about to enter the Kingdom of Bhutan, the world’s only country with a nationwide ban on tobacco sales and public smoking. The customs declaration form still shows an allowance of 200 cigarettes per traveler, but that paragraph has been crossed out with ballpoint, suggestion that the information has recently become outdated. There is no mention of any new allowance or of what might happen to people caught violating the rules.

To ease my mind, I re-read an article in the in-flight magazine that describes Bhutan as a peaceful Buddhist country, with friendly people and a benevolent king. But my thoughts drift to the novel Lost Horizon, James Hilton’s classic about a group of air travelers who crash near Tibet and are taken to an idyllic, hidden mountain resort, Shangri-la—only to find that they may never leave. Travel experts have likened Bhutan to Shangri-la, and I am not certain whether to draw comfort from that comparison now.

As the plane touches down, a group of relieved passengers burst into applause. I, on the other hand, start to sweat. Noel might win this bet.

Smoke-free society

I have come to Bhutan to see what a smoke-free society looks like. Is it the utopia the public health movement makes it out to be, or is it a make-believe paradise with an Orwellian tinge, like Hilton’s Shangri-la?

One thing is certain: Bhutan’s experiment is unprecedented in modern history. Even as governments around the world step up their anti-smoking rhetoric, none seems prepared to take the argument to its logical conclusion.

None except Bhutan. While ratifying the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in August 2004, the country’s national assembly announced that it would go beyond the treaty’s proposed tax hikes and advertising restrictions and declared tobacco illegal.

After a three-month transition period during which shopkeepers were allowed to exhaust their stocks, the ban became effective in December 2004, with authorities in Thimphu igniting bonfires of unsold cigarettes and stringing banners across the main thoroughfare exhorting people to kick the habit.

Cautioning people to take its decision seriously, the government announced hefty fines for violators. Shopkeepers caught selling cigarettes risk losing their business licenses and can be fined up to $220, a hefty sum in a country with a per-capita income of $660. Two months later, and perhaps a tad redundantly, given that cigarettes were no longer legally available, Bhutan banned smoking from all public places. The only place where smokers may still light up is at home.

Bhutan’s bold move is significant not only because it is unprecedented, but also because it renders obsolete one of the tobacco industry’s most effective defenses. For many years, cigarette companies have silenced their detractors by reminding them that tobacco is a legal product everywhere. If tobacco is truly the evil weed its critics purport, governments should ban it—which of course they never did, conscious of the impracticalities and loss of tax revenues associated with such a measure.

Until now.

A world apart

One of the reasons Bhutan managed to pull off what other countries can seemingly only pay lip service to might lie in its isolation, both geographically and culturally. Wedged in the Himalayas between China and India, Bhutan remains a closed society that regards outside influences, including smoking, with suspicion.

This becomes apparent the minute you start planning a visit—you can’t just buy a ticket and go. One would expect an impoverished yet stunningly beautiful country like Bhutan to welcome tourists with open arms—and count the dollars. Yet Bhutan didn’t even permit tourism until 1974, and the government continues to restrict its numbers (only 9,000 people visited in 2004), willfully forgoing significant amounts of revenue. Visitors are required to purchase tours with strictly supervised itineraries and pay all expenditures in advance.

The only way for me to experience the world’s first and only smoke-free society was to sign up for a guided tour of Dzongs and local festivals. Not that I minded, of course. Bhutanese culture is quite fascinating and its natural beauty unrivaled. But it also limited my freedom as a journalist. For example, when the agenda called for a tour of Thimphu’s textile museum or a visit to a shrine honoring Guru Rinpoche, the saint who brought Buddhism to Bhutan, I could hardly insist on visiting the health ministry instead. Blessed with a direct mandate from God, King Wangchuk would probably have felt little inclination to justify his policies to Taco Tuinstra from Tobacco Reporter, anyway.

Nonetheless, between temple visits and scenic drives, I managed to get a good feel for life in a smokeless society by speaking with several current and former smokers, a few shopkeepers and a police captain. I also talked at length with my guide, Gopal Wanghug, an ex-smoker who says the ban forced him to kick the habit because, even though cigarettes are still available on the black market, they have become quite expensive. Despite the discomfort associated with quitting smoking, Wanghug says he and many other Bhutanese smokers support the ban. I couldn’t determine whether, as a state employee, he felt he had to defend the official line, or whether his feelings were genuine.

Despite my waving of increasingly larger wads of cash, the shopkeepers I spoke to insisted they carried no undocumented inventory for smokers willing to pay the right price. Captain Dorji Tshering of the Thimphu police force said that, personally, he had not caught any vendors selling illegal cigarettes, but he knew of colleagues who had. A private security guard later boasted that “rules are meant to be broken,” but he didn’t light up in my presence, professing he had left his cigarettes at home.

Shangri-La

While each of my conversation partners had his own perspective, they all agreed that only in Bhutan could a government get away with a blanket tobacco ban. The country, they said, is different.

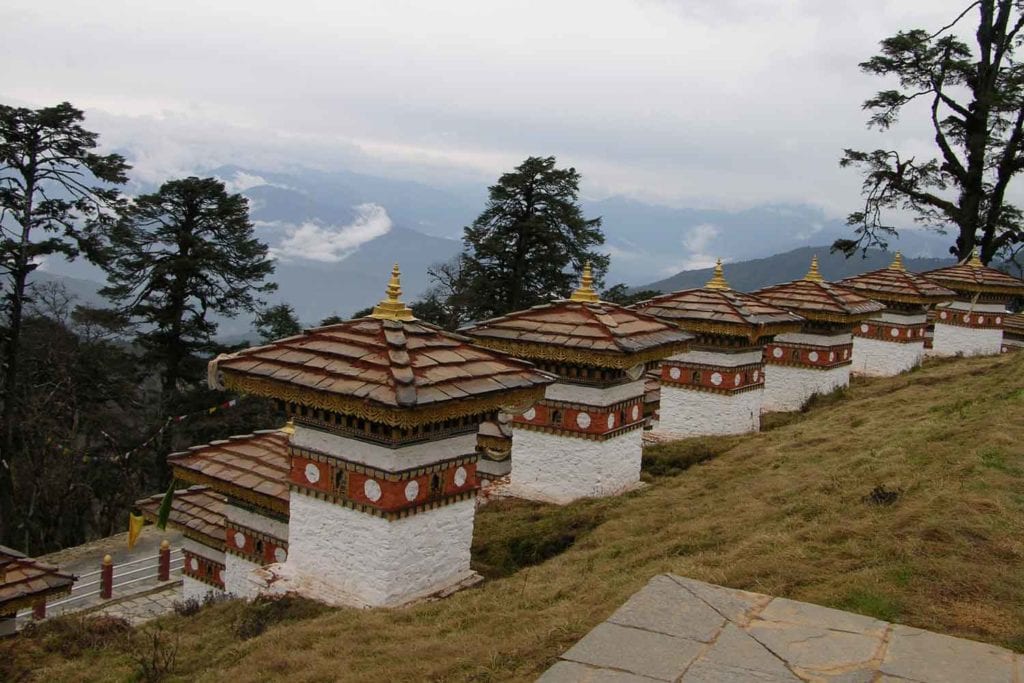

They might be on to something. Through most of its history, Bhutan has marched to its own peculiar drumbeat. The country’s first paved roads date from 1961. Before 1986 it had no banks. Until 1999, there was no television or access to the Internet. Mobile phones, too, are a recent phenomenon, although transmission towers continue to be greatly outnumbered by Buddhist prayer flags. Thimphu still advertises itself as the only national capital without a traffic light.

The government is governed by a king, who is regarded as an incarnation of God and as such is universally obeyed. While other nations fret about their gross domestic product, impoverished Bhutan emphasizes “gross national happiness.”

And it’s not just smoking that’s banned. To preserve its pristine environment, Bhutan prohibits the use of plastic bags and sales of secondhand cars, which emit more pollution than do new vehicles. Environmental protection ranks high among government priorities and may have played a role in the decision to ban smoking. It’s interesting to note that when Thimphu authorities torched unsold cigarettes in the days before the ban took effect, their superiors quickly put an end to the practice, complaining about air pollution.

Wanghug, my guide, also told me that, while anti-tobacco sentiments are a recent phenomenon in most Asian countries, they have deep roots in Bhutan. Last year’s widely published announcement was merely the culmination of an anti-smoking policy that had been growing progressively stricter for years. Prior to the nationwide ban, tobacco sales had already been banished in 18 of the country’s 20 dzongkags. The new rule only extended prohibition to the last holdouts—the capital district of Thimphu and the eastern district of Samdrup Jongkar. Sales of tobacco products in duty-free shops have been banned since January 2003.

In fact, Bhutan’s anti-tobacco tradition can be traced to the nation’s creation. The founder of modern Bhutan, the warrior monk Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, enacted the first ban on public smoking when he outlawed the use of tobacco in government buildings in 1629. Guru Rinpoche, Bhutan’s spiritual father, believed that the tobacco plant sprang from the menstrual blood of a female devil who wished for an intoxicant that would obstruct religious practice. Although Buddhist scholars suspect Rinpoche may have been referring to opium, the government clearly felt comfortable extending his concerns to tobacco.

Unlike governments in other countries, Bhutan didn’t have to worry about alienating voters or special interest groups. Bhutan neither grows tobacco nor manufactures cigarettes, which means there were no tobacco farmers or cigarette factory workers to placate. Tax revenues weren’t much of a concern, either. Smokers account for less than 5 percent of a population that is estimated at less than 2 million. The use of chewing tobaccos is reportedly more widespread, but there are no reliable statistics. Many Bhutanese prefer chewing betel nut, a stimulant that turns saliva red and that, like tobacco, has been linked to health problems. Needless to say, the sale and consumption of betel nut remains legal.

Bhutan’s remote location, combined with its small population, has made the country uninteresting to multinational cigarette makers pursuing economies of scale. As a result, the most popular cigarette brand in Bhutan was not Marlboro or Mild Seven but Wills, which is manufactured by ITC in neighboring India. Even so, the declared value of all tobacco imports from India was only 200,000 ngultrum—a mere $400—in 2003, according to Kuensel, Bhutan’s English-language newspaper. How much tobacco entered—and continues to enter—Bhutan unofficially remains anyone’s guess.

Setting a precedent

Is Bhutan as different as my sources suggest, or should the tobacco industry be concerned about other countries copying its policies? The Bhutanese government clearly wishes for the latter. During a meeting of health ministers at the WHO in Geneva, Bhutan’s secretary of health, Sangay Thinley, expressed hope that Bhutan’s example would prompt other countries to follow suit.

So far, that hasn’t happened. Even a WHO official, while praising Bhutan’s initiative, admitted that a blanket ban might prove impractical in other countries. Indeed, Bhutan’s northern neighbor, China, is home to one-third of the world’s smokers and its government is said to derive almost 10 percent of its revenues from taxes on tobacco products. Following its ratification of the FCTC, China will likely place more restrictions on its tobacco industry. Considering the tobacco industry’s enormous economic clout in that country, however, it is safe to assume that Beijing will not slaughter the goose that lays it golden eggs.

South of the border, the Indian government, too, has ratified the FCTC, restricted tobacco advertising and limited smoking in public places. A blanket sales ban appears unlikely, however, as bidi cigarettes continue to enjoy wide popularity among smokers and the bidi industry employs millions.

Farther from home, countries such as Ireland and Italy have passed far-reaching public smoking restrictions, but they are not outlawing tobacco sales as such.

Perhaps the country that is closest to following Bhutan’s example is South Korea, where a health-minded member of Parliament has been collecting signatures to prohibit domestic manufacturing of cigarettes within a decade.

Nevertheless, while Bhutan is an unusual place and its cigarette market tiny, the industry would be unwise to dismiss its radical experiment completely. For example, nine cancer centers in Asia recently signed an agreement to work with their respective governments to ban tobacco. The group is not comprised of eccentric mountain kingdoms like Bhutan, but of leading industrial nations, including Singapore, Japan and China.

Anticlimax

My editorial mission was a success: I experienced life in the world’s first smoke-free society and realized that it will probably remain the only one for the foreseeable future. But what about my personal assignment; was it successful also? Here’s what happened: When a customs officer told me to open my bag, I lit a cigarette, blew smoke into his face and lectured him on smokers’ rights and the importance of mutual tolerance. Persuaded by my compelling arguments, the official called the royal palace. King Wangchuk, embarrassed about his mistake, revoked the ban that very day.

Okay, I made that up. Instead, increasingly concerned about an involuntary extended stay in Shangri-la if someone were to search my bags, I silently conceded defeat before I even left the airplane. As the passengers shuffled toward the exit, I sneaked the cigarette pack into the seatback pocket of a first-class traveler—so authorities wouldn’t be able to trace me via my seat number if they found the pack. I met my guide and toured the country, which, as described in Druk Air magazine, was stunningly beautiful and full of friendly people.

Then, on the last day of my stay, as I was packing my suitcase, something fell out the pocket of a shirt I hadn’t worn during the trip. It was a cigarette! Or rather, it was a pen shaped like one; a promotional gimmick that Tobacco Reporter once gave away at trade exhibitions.

The “cigarette” looked remarkably realistic; it even had “ash,” which doubled as the pen’s cap. I told my guide I wanted to run a quick errand before driving to the airport, and rushed to Thimphu’s central square, which was only a block away from our hotel.

Standing on in the middle of the square, I hesitated again, having to remind myself that I wasn’t breaking any laws. I stuck the pen in my mouth, cupped my hands around the end as if I were lighting a real cigarette, and then pretended to smoke.

I looked around triumphantly, but nothing happened. The passersby just ignored me. Then, five young boys entered the square to play football. As they walked by, the tallest one whispered something to his friends and they giggled. But after the last boy had passed, he suddenly turned around and gave me the thumbs-up sign.

What a victory. I had defied the world’s strictest anti-smoking regime and the local population worshipped me as a hero defending their rights. Well, maybe not. Perhaps the thumbs-up sign means something else in Bhutan than it does in western Europe or America. I should probably count myself lucky if Noel allows a fake cigarette to win the bet.