Tobacco growers deserve better

By George Gay

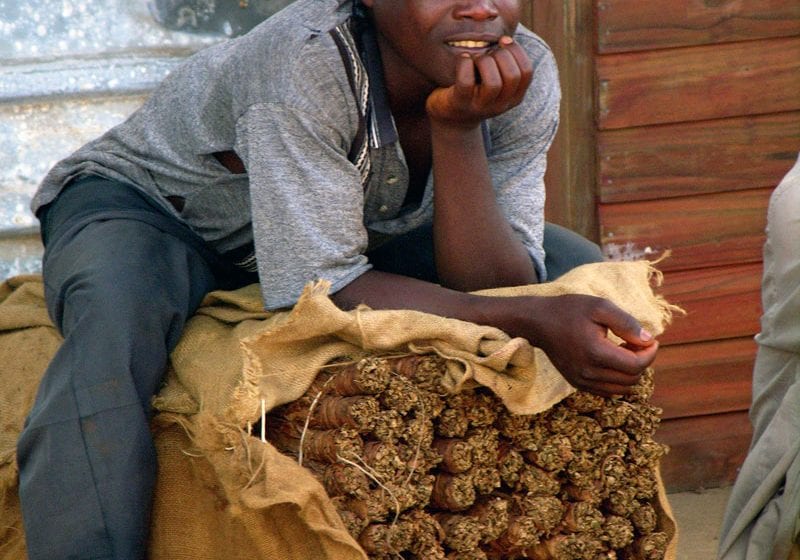

In the 20 years from 1996 to 2016, the average price paid to Zimbabwe growers for their flue-cured tobacco rose by 0.34 percent. That’s worth repeating: 0.34 percent over 20 years.

It rose from US$2.94 per kg to $2.95 per kg. To say this was parsimonious on the part of the buyers would be thoroughly mean to the word parsimonious.

I wonder in what universe such a price development would be seen to be fair—if, indeed, it can be referred to meaningfully as a development. In which corporate responsibility report does this shine out as a beacon for others to follow?

It surely cannot be seen to be fair in this universe where the major tobacco companies—which are the ultimate buyers of this tobacco—are imposing on their customers cigarette price increases of, what, 6–8 percent a year, excluding taxes?

Let it never be said again that Zimbabwean tobacco growers are tobacco industry stakeholders, unless the imagery is extended to have them trying to fend off the pointy end of a stake wielded by the manufacturers and those that buy leaf on their behalf.

If, according to my back-of-the-envelope figures, the amount paid to flue-cured tobacco growers in Zimbabwe had grown at the lower end of the manufacturers’ price rises (at 6 percent a year, from $2.94 per kg in 1996), by 2016 those growers would have been paid $9.42 per kg. Even if they had been paid a miserly 1 percent increase each year, by 2016 they would have been paid $3.54 per kg.

OK, to give a fuller picture, I should say that the average price during those 20 years did go up by 24.8 percent to $3.67 per kg in 2013, but then it had crashed by 45.2 percent to $1.61 per kg in 2005. In any case, if leaf prices had increased by 6 percent a year, they would have been at $7.92 per kg in 2013. Even if they had gone up by only 1 percent a year, they would have been at $3.45 per kg. Increasing by 1 percent or 6 percent, the average price would have been $3.21 per kg or $4.97 per kg, respectively, in 2005—that is two or three times the price paid.

The slippery concept of quality

What might the reasons for such pricing be? Well, one thing that is often said is that prices—in any industry—are set by markets that are governed by supply and demand. This implies that those markets are reasonably “free,” but in our neoliberal world they are clearly not. They are controlled by huge, powerful corporations, and as can be seen from the above prices, power concedes nothing to the powerless.

One reason that is given for low prices is that the quality of the tobacco is low. This is a difficult one to argue because quality is a slippery concept. I was reading recently a piece in which it was said that Robert Pirzig had started writing Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance because, as a new university lecturer, he noticed that he had an obligation to teach quality, but that nowhere was it defined what quality was. I’m not saying that quality is not defined when it comes to leaf tobacco; it’s just that it is a concept that is difficult to nail down, especially at the time farmers’ bales are bought. And under such circumstances it is open to manipulation. As playwright George Bernard Shaw once observed, every profession is a conspiracy against the laity.

And there is another reason why I tend to be suspicious of the quality argument. In the 20-year time frame of the grower-price stagnation described above, the volume of the cigarette brands on which the major manufacturers target their marketing efforts—each uses a different term to describe such brands—has been increasing, though very lately sometimes only in relation to overall volumes. Now these targeted brands I take it are premium-price or at least higher-price brands, and, again, presumably, they are made with better-quality leaf than are other brands. So the question arises as to where this increased volume of quality tobacco has been coming from. It is clearly not coming from Zimbabwe because, otherwise, prices would have been going up—or they would have been according to the “good quality equals higher prices” argument.

Low quality, it seems to me, is used, along with its partner, high quantity as a sort of Catch-22 whereby farmers are only rarely allowed to take home a few extra cents. If the weather is helpful, I guess the chances are that the quality will be at least reasonable and the quantity on the high side, so any chance that prices will be good because of the quality is cancelled out by the quantity’s being too high—by the entrance of “market forces.”

The average price paid in 2008, when Zimbabwe’s farmers produced a very small crop that was close to 49 million kg, was $3.21 per kg. We can assume, I think, that in 2008, with much of the crop being grown by inexperienced farmers, the leaf produced was not of the highest quality. But $3.21 per kg was more than was paid in the last years of commercial growing, or in 2016, by which time, presumably, the small-scale farmers were more used to growing tobacco and quality was improved.

I would speculate that a higher price was paid in 2008 because buyers wanted to encourage farmers to produce more, as they did the next year and, especially, in 2010. This seems to be an indication that prices are linked to quantity in certain circumstances. Prices go up if the quantity falls below a point at which manufacturers become concerned that, if there are another two or three years of low volumes, their manufacturing capability might be endangered.

Patronizing

Some people will argue that the above isn’t fair to tobacco companies because part of the reason why prices have stagnated during the period under review is that an increasing amount of contract farming has been brought in, and under that system certain inputs needed by growers have been provided—factors that should be considered in looking at grower prices. To those people I would say two things. The first is that I am willing to accept this, but only if published grower prices show, in a meaningful way, the value of whatever other benefits the growers are receiving. After all, sustainability demands transparency.

The other thing I would say is that if growers are being provided with inputs, such as fertilizer, and are told when to apply them, then it should be discussed whether those growers are actually employees of the buyers who are directing nearly their every move. This certainly seems to be the case in regard to farmers working according to integrated production systems. And if they are employees, then they should be provided with whatever benefits the country in which they operate decrees they should receive as employees: holiday pay and sick pay, for instance.

Some other people will say that tobacco companies provide benefits to the communities where tobacco is grown, but often, to people such as me, these benefits are patronizing bordering on colonialism. And, ironically, you will hear people try to counter the charge that they are being patronizing by saying that these benefits are provided because if growers are handed money they will spend it instantly, leaving no cushion for lean times. I rest my case.

We in the West are happy to lecture the people of Africa about good financial management, but we should reflect that it wasn’t the people of Zimbabwe, Malawi or Zambia who crashed the financial system in 2008. And it wasn’t tobacco farmers who predicted in 2007 that the world’s economy was in good shape; it was the International Monetary Fund. A little humility never goes amiss.

Most of the above comments have been about Zimbabwe, but they could just as well have been directed at many other tobacco growing countries. When I had nearly finished this piece, it came to my attention that a disagreement had blown up about the battle against the use of child labor in Malawi. I haven’t had time to examine this issue, but I think one thing bears repeating. One of the parties to the disagreement made the point that certain initiatives aimed at eliminating child labor in tobacco growing insufficiently addressed the root cause of this problem: the endemic poverty among tobacco farmers. And he said that that poverty was being exacerbated by contracting schemes developed by the very companies funding some of the initiatives.

Although I did not have time properly to look into this matter and so have no idea about the benefits or otherwise of the contracting schemes mentioned, I believe that it is not in doubt that poverty is endemic to Malawi, a country whose economy relies heavily on selling the most important raw material to a hugely profitable industry in which executives are each paid millions of dollars per year. Nor is it in doubt that that poverty can be laid, in no small part, at the feet of the tobacco industry. Another of the parties to the disagreement—on the other side of the disagreement—was kind enough to tell me:

“According to the FAO [the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations], more than 50 percent of Malawi’s population is still living in poverty. Agriculture is the backbone of the economy of Malawi, with 80 percent of Malawians depending on it for their livelihoods. Tobacco is the main crop, accounting for almost 50 percent of the country’s exports according to the World Bank. Agriculture in Malawi, in general and including in tobacco growing communities, tends to be subsistence in nature, which means that equipment, sustainable technologies and finance are often beyond [the] reach of small-scale farmers.”

In July, a generally upbeat piece in Tobacco Reporter started with this sentence: “Following several disappointing seasons, Malawi tobacco growers have reason to smile again.” “Disappointing” seems to be an understatement. I imagine that following these disappointing seasons, some of the tobacco growers, along with their families, would have gone hungry. That is devastating. We in the West like to lecture these people on how to do things, but I wonder how many of us could survive such devastating times—who wouldn’t go to pieces in such circumstances? How many of us could get by if our salaries were “disappointing” for several years and then less than disappointing for one year? A little humility and a little empathy never goes amiss.

It is long past the time when the tobacco industry should have started worrying less about how much sand is in with the leaf it buys and more about how much food is in the mouths of the people who grow that leaf and the families they support. Just because the industry can buy leaf on the cheap doesn’t mean that it should.