Zimbabwe’s crop volume has recovered from land reform, but plenty of challenges remain.

By Taco Tuinstra

Plenty of ink has flowed describing the economic significance of tobacco. The direct and indirect employment created, the hard currency earned, the tax revenues generated—the figures never fail to astonish. Yet even the most impressive statistics and detailed spreadsheets don’t drive home the point in the way that a field trip does. If you want to see the multiplier effect in action, you should visit one of the tobacco sales floors in Harare, Zimbabwe.

During the selling season, the areas surrounding these facilities turn into makeshift villages, occupied by farm families, vendors and creditors hoping to cash in on the farmers’ earnings. From shacks made of scrap wood, carton and tarpaulin, traders peddle wheelbarrows, hessian sheets and fertilizer, among other farming necessities.

But the offerings aren’t limited to agricultural goods. Mannequins draped in various garments sit next to portable solar panels, which in turn are flanked by stereo systems. Farmers can buy computer memory cards, get their hair cut or charge their phones at a diesel generator. For the libidinous, there is female company available, according to a long-time Harare resident with no ties to the tobacco industry.

The hive of activity surrounding the tobacco floors hints at the central role that the crop continues to occupy in Zimbabwe. Roughly 100,000 farmers—most of them small-scale producers—grew 200 million kg of tobacco here this season. More than 90 percent of the crop is exported, earning the country much-needed foreign currency. In 2017, tobacco generated $600 million for Zimbabwe. Encouraged by near-perfect weather conditions this growing season, the trade hopes to top that figure in 2018.

But the bustle also reflects the massive change that has taken place in Zimbabwe’s tobacco industry. Until the late 1990s, the business was dominated by large-scale farming. During those times, a handful of farmers may have sat around in the auction cafeteria, discussing the latest rugby match while awaiting the sales of their leaf. Auctioneers would chant their songs and leaf buyers would shout their preferred prices, but compared with the spectacle surrounding the sales floors today, the auctions were a sea of tranquility. The same 200 million kg was produced by only a few thousand growers back then, creating an entirely different dynamic.

Land reform

Zimbabwe’s tobacco sector used to be the envy of the world, with state-of-the-art agricultural research, first-rate farming methods and a world-class marketing system, but it was controlled by a minority—white descendants of European colonialists. Up until the turn of the century, Zimbabwe’s prime farm lands remained in the hands of a group that accounted for a tiny share of the population.

At independence from Britain in 1980, plans were made for the transfer of lands from whites to blacks on a willing-seller-willing-buyer basis, but for various reasons, including lack of funds, progress was slow. In the late 1990s, President Robert Mugabe, alarmed by his declining popularity, lost patience and started evicting white farmers from their lands. He encouraged mobs to invade the farms and declared all land property of the state. But instead of benefiting the black landless masses, the best farms ended up in the hands of generals, politicians and police commissioners—people selected for their connections rather than their farming skills.

The result was as predictable as it was devastating. Many previously productive farms turned into grasslands, affecting not only tobacco but also food crops and livestock. Once a major exporter of food, Zimbabwe became reliant on imports to feed its population—but without generating the foreign currency required to pay for them. By 2008, Zimbabwe’s tobacco crop had plunged to 49 million kg, causing exporters to lament that the former tobacco powerhouse had become an “opportunity market.” At its peak, in 2000, Zimbabwe produced 237 million kg, making it one of the world’s largest tobacco exporters.

Unable to balance its budgets, the government started printing money, spawning the worst case of hyperinflation in modern history. At one point, it was cheaper for a farmer to let his tobacco rot in the barn than to sell it for rapidly depreciating Zimbabwean dollars. In 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its currency in favor of the U.S. dollar. The last batch of Zimbabwean dollars printed included a z$100 trillion bill—the equivalent of perhaps us$0.40, depending on the time of day.

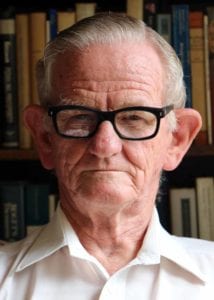

The introduction of “real” money brought back a degree of stability, but tobacco growers still struggled. The transition from large-scale to small-scale growing caused many agricultural support services to collapse because the volumes no longer added up. “Whereas a mechanic in town might be happy to service 10 tractors at a single, large farm, the calculation changed when he had to travel to 10 different destinations spread throughout the countryside,” says John Robertson, an economist in Harare. Fertilizer companies accustomed to selling by the truckload suddenly were dealing with customers buying one wheelbarrow load each.

The rise of contracting

Knowing they could be evicted at a moment’s notice, the old-style commercial farmers who remained on their lands were reluctant to invest. The new farmers who wanted to grow tobacco, meanwhile, were unable to obtain funds. They had been resettled without receiving land titles, which meant that they could not use their land as collateral to secure bank loans.

Concerned about their supplies, leaf merchants started contracting directly with tobacco farmers in the same way they had been doing in Brazil, another market characterized by small farms and vast volumes. Under this system, the dealers provide growers with seeds, fertilizers and crop-protection agents, along with agronomic advice. The cost of the inputs is deducted from the sales price after the tobacco has been grown. Driven by continued uncertainty about land tenure and customers’ increasing insistence on traceability, contracting spread rapidly in Zimbabwe. Today, 83 percent of the country’s tobacco is grown under such arrangements.

The direct involvement of leaf merchants, together with the enthusiasm of many new farmers, helped volumes recover. In 2014, the crop surpassed 200 million kg for the first time in more than a decade. Quality is up, too, although today’s Zimbabwean tobacco is very different from that grown at the turn of the century—a development that reflects changes not only in the grower base but also in customer demand.

“Quality” refers to the styles of tobacco in demand as well as the smoking quality, explains David Taylor, regional leaf production director for Mashonaland Tobacco Company (MTC), a subsidiary of Alliance One International. In the 1990s, the local market was dominated by European customers; today, most Zimbabwean tobacco goes to Asia. With cigarette consumption rapidly declining in Western markets, China now accounts for half of Zimbabwe’s crop by volume and more than half by value, according to Taylor. Contrary to the European buyers, who tend to prefer a riper, thinner style, the Chinese prefer a cleaner, “bodied” style of leaf, he says.

“Quality” refers to the styles of tobacco in demand as well as the smoking quality, explains David Taylor, regional leaf production director for Mashonaland Tobacco Company (MTC), a subsidiary of Alliance One International. In the 1990s, the local market was dominated by European customers; today, most Zimbabwean tobacco goes to Asia. With cigarette consumption rapidly declining in Western markets, China now accounts for half of Zimbabwe’s crop by volume and more than half by value, according to Taylor. Contrary to the European buyers, who tend to prefer a riper, thinner style, the Chinese prefer a cleaner, “bodied” style of leaf, he says.

Farmer and buyer representatives agree that the new farmers have performed remarkably well, considering the challenges. The gap in quality between their leaf and that produced by commercial farmers is rapidly closing, according to industry experts. “From field-handling, reaping, curing, packaging—there has been a vast improvement over time,” says Rodney Ambrose, CEO of the Zimbabwe Tobacco Association (ZTA), a growers’ organization. According to Alexander Mackay, managing director of Premium Leaf Zimbabwe, some small-scale farmers are now producing better quality than even their larger counterparts. “It’s a feather in their cap,” he says.

Some believe there is room for improvement in grading, however, pointing out that individual farmer volumes are often too small to create consistent grades in a bale. Maintaining and improving standards will require continuous education, according to Taylor, because the grower base is constantly evolving. Attracted by the comparatively high prices for tobacco, new and inexperienced farmers enter the field every season.

Planting trees

In addition to good agronomical practices, merchants increasingly stress the importance of sustainable production in their training programs, particularly from an environmental perspective. Land reform has contributed to a rapid depreciation of woodland in Zimbabwe. Every year, the country loses 300,000 hectares of forest, according to the Forestry Commission of Zimbabwe. And even though only an estimated 15 percent of that figure is attributed to tobacco curing—cutting trees for cooking fuel and general land clearing are believed to be the biggest causes of deforestation in Zimbabwe—the industry is keen to reverse the trend. “If we continue at this rate, we will run out of curing wood within five years,” cautions Ambrose.

In addition to good agronomical practices, merchants increasingly stress the importance of sustainable production in their training programs, particularly from an environmental perspective. Land reform has contributed to a rapid depreciation of woodland in Zimbabwe. Every year, the country loses 300,000 hectares of forest, according to the Forestry Commission of Zimbabwe. And even though only an estimated 15 percent of that figure is attributed to tobacco curing—cutting trees for cooking fuel and general land clearing are believed to be the biggest causes of deforestation in Zimbabwe—the industry is keen to reverse the trend. “If we continue at this rate, we will run out of curing wood within five years,” cautions Ambrose.

Large-scale tobacco farmers use coal to cure their tobacco, but this fuel type is ill-suited for small operations due to price and practical considerations. The country’s primary coal mine, in Hwange, is hundreds of kilometers from its tobacco-growing region, adding to transportation cost. In addition, curing barns that run on coal require fans—and thus power—for proper operation. Electricity, however, is unreliable or unavailable in many rural areas. So, the industry is tackling the problem by increasing the supply of wood while reducing its consumption.

The Sustainable Afforestation Association (SAA) was created in 2013 by Zimbabwe’s tobacco merchants specifically for this purpose. Funded by a voluntary levy of 1.5 percent on leaf dealers’ purchases, the association aims to create sustainable wood sources, conserve indigenous forests and research alternative fuels. Because native trees, such as msasa, can take up to 100 years to mature, the SAA has been planting eucalyptus in Zimbabwe. Originally from Australia, this tree genus can be harvested after a mere seven years.

Rather than simply handing tree seeds to tobacco growers—which hasn’t worked well in the past—the SAA partners with farmers to set up commercial plantations. After each harvest, the association gets 80 percent of the trees, which it sells to tobacco growers, and the farmer gets 20 percent, which he can use as he likes. At the end of the contract, the farmer owns the plantation.

Andrew Mills, operations director of the SAA, estimates that to cure a tobacco crop of 200 million kg, the industry requires 12,000–13,000 hectares of trees. The SAA plants approximately 4,000 hectares per year—14,500 hectares to date—which means the program is part of the solution and other sources are needed. As additional support to SAA’s program, tobacco merchants operate their own tree-planting schemes. Also, in 2015, the government introduced a levy on growers’ sales to fund additional reforestation initiatives. It has collected $20 million to date, but due to dispute over who should manage the money—the Tobacco Marketing and Industry Board (TIMB) or the Forestry Commission—not a single tree has been planted from this fund yet.

On the demand side, stakeholders are trying to reduce consumption with more efficient furnaces and alternative fuels. The latter has proved challenging, according to Mills. “The SAA looked at biogas but couldn’t make it work,” he says. “Ethanol cures well but isn’t viable because the process uses too much of it.” Mills sees potential in briquettes made from forestry byproducts. “The forestry industry generates lots of waste that can be used for this purpose,” he says.

The industry’s concern about sustainability extends beyond environmental issues. Earlier this year, Human Rights Watch published a report detailing instances of child labor on Zimbabwean tobacco farms. But Isheunesu Moyo, public relations communications manager at the TIMB, says the report does not necessarily reflect reality. “They interviewed 125 out of 100,000 growers,” he says. “Of course, every instance of child labor is one too many. But how representative are the findings?”

The shift from large-scale to small-scale farming has dramatically changed the tobacco workforce. Whereas the old-style commercial farmers employed hundreds of workers, the resettled farmers often rely on family members to work the land.

The tobacco merchants insist they have zero tolerance for child labor. Their contracts include strict clauses against the practice. For example, MTC visits its growers every two weeks to train them on the best agronomy and labor practices (ALP). Any labor incidents are logged and immediately followed up upon by the company’s ALP team, which has been employed exclusively to train farmers on labor-related issues, according to Taylor. A farmer violating the specified agricultural labor practices risks losing his or her contract with MTC.

Of course, growers operating on their own, without contracts, face less scrutiny. “That’s where the system breaks down,” says Taylor. Such lack of traceability has prompted some players to abandon the auctions altogether Others, however, see the facilities as a useful benchmark for the contracts. Currently the average price on the first day of auction sales serves as the floor price for contracts.

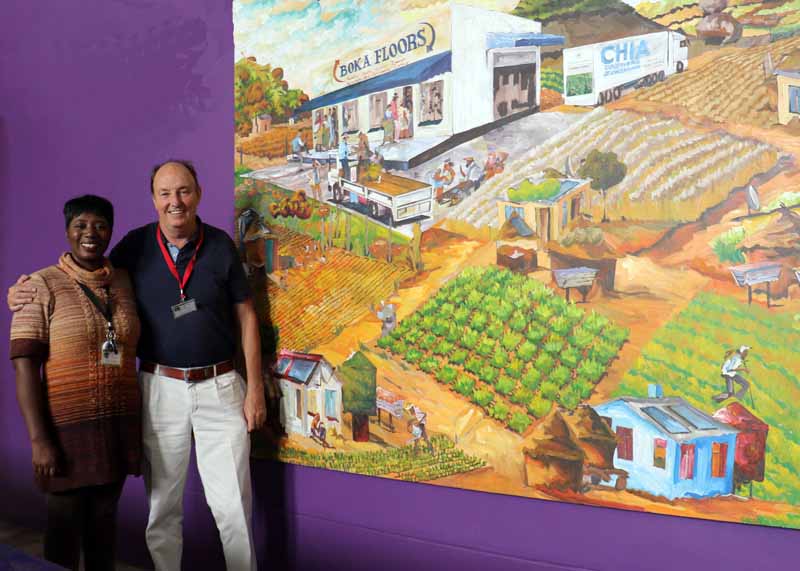

While contracting presents many benefits to farmers—a guaranteed market, agronomic support and access to inputs—there is also a downside, according to Ambrose. “Growers never know if they are getting the best deal,” he says. “We like buyers to actively compete for our tobacco.” The trend, however, is toward even more contracting, and the decline in tobacco business has already prompted the auction floors to look into supplemental activities to make up for lost revenues. Boka Tobacco Floors, for example, is experimenting with the production of chia, a flowering plant in the mint family.

Politics

In the meantime, all eyes are on the country’s presidential elections, scheduled for this summer. The bloodless coup that ended Mugabe’s 38-year reign in November has raised expectations of an economic turnaround, which should also benefit the tobacco industry. While some remain skeptical, describing the situation as “same train, different driver,” many are hopeful that, once he has a proper mandate, President Emerson Mnangagwa will be able to change things for the better.

“The president is making all the right noises,” says Mackay. Among other things, Mnangagwa has declared Zimbabwe “open for business” and rolled back legislation requiring all firms to be majority black-owned. To international tobacco companies, his attitude marks a welcome change from that of the previous president, who, toward the end of his tenure, was outright hostile to foreign investors.

During Tobacco Reporter’s visit in April, Harare’s hotels were full of foreign businessmen testing the waters, including South African farmers, Australian miners and representatives of various agribusinesses. An employee at the famous Meikles hotel reported full occupancy for the first time in nearly a decade. Even some of the evicted white farmers have reportedly returned. In some cases, they are renting back their farms from the new owners who accumulated debt because they did not know how to farm.

Of course, Zimbabwe’s long-suffering economy will not be fixed by decree. To give farmers greater security of tenure, the government has proposed 99-year land leases, but the banks remain skeptical. “To serve as collateral, an asset must be easily transferable,” explains Robertson. The lease document under discussion, he says, includes 48 pages of conditions. “A similar contract in Europe takes up only a few sheets.”

A big challenge for the new president will be reforming the civil service, which remains staffed with people appointed by the old regime. But change is evident already. One of the biggest drivers behind last year’s revolution was people’s frustration with corruption. Eager to supplement their meager salaries, Zimbabwean traffic police would set up roadblocks and fine motorists for invented infractions. They would find problems with a vehicle’s headlights, fire extinguisher or spare tire. “It would cost you $10 to $20 in fines every time you traveled to town,” says Robertson. Mnangagwa ordered the police off the roads, and the interference stopped overnight. But the absence of law enforcement also has a flipside: The number of unroadworthy vehicles and unlicensed drivers on Zimbabwe’s streets is said to have increased considerably since November.

A big challenge for the new president will be reforming the civil service, which remains staffed with people appointed by the old regime. But change is evident already. One of the biggest drivers behind last year’s revolution was people’s frustration with corruption. Eager to supplement their meager salaries, Zimbabwean traffic police would set up roadblocks and fine motorists for invented infractions. They would find problems with a vehicle’s headlights, fire extinguisher or spare tire. “It would cost you $10 to $20 in fines every time you traveled to town,” says Robertson. Mnangagwa ordered the police off the roads, and the interference stopped overnight. But the absence of law enforcement also has a flipside: The number of unroadworthy vehicles and unlicensed drivers on Zimbabwe’s streets is said to have increased considerably since November.

As it awaits the changes, the Zimbabwean tobacco industry can take comfort from the fact that, even as global cigarette consumption declines, its leaf will likely remain in the demand. Only a handful of countries can produce the flavor style tobacco that Zimbabwe is famous for, and industry experts believe that cuts in production will take place first in origins with less popular styles. “There is little unsold stock left at the end of each season, which proves there’s a market for our leaf,” says Ambrose. The number of buyers competing in Zimbabwe, too, seems to bear out that view. The TIMB licensed 23 contractors and 29 buyers this season, including Premium Tobacco, the world’s largest privately held tobacco merchant, which entered the market in 2016 with the acquisition of Tribac. With new customers in northern Africa and the Middle East, Zimbabwean leaf is now exported to 47 countries—up from 30 in 2011, according to ZTA.

But even with still-healthy demand, the industry knows it will have to be on top of its game to succeed in a shrinking global cigarette market with increasingly demanding customers. Zimbabwe’s cost of production is high compared with that in other origins, but in a global market, the margin for price increases is limited. The use of the U.S. dollar means Zimbabwe cannot devalue its currency and make tobacco earnings go further domestically. In such an environment, the only way to improve farmer income is through higher yields and higher quality. Among other things, that requires the consistent application of good agronomic practices. Earlier this year, Zimbabwe struggled to contain an outbreak of potato virus Y. The key to the future, according to many stakeholders, will be property rights. Proper land tenure would allow farmers to fund their own operations and dealers to focus on their core business. “If that’s done correctly, we could have 250 million kg of tobacco and a huge maize crop,” says Mackay.