Christian Hinz and Lisa Esser evaluate the impact of new plain packaging requirements for RYO paper packaging.

By Stefanie Rossel

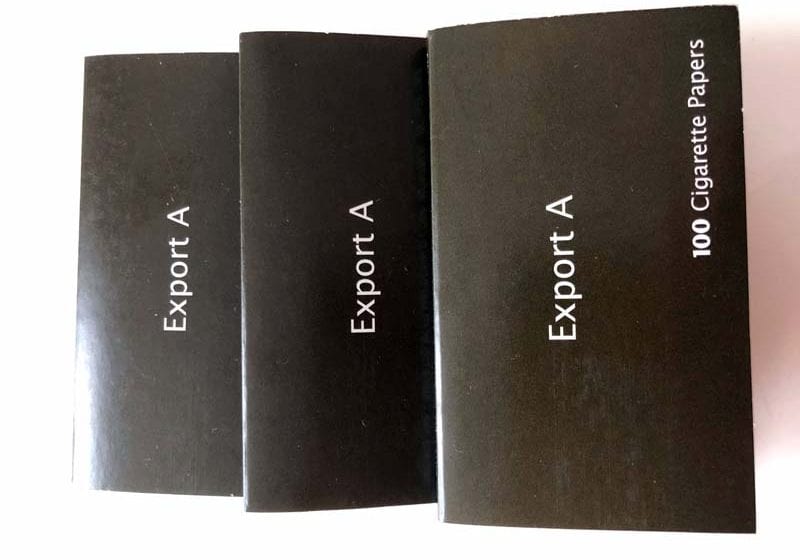

Plain cigarettes packaging has been around for almost eight years now. Recently, Canada and Israel took the concept to a new level, requiring, for the first time, that the packaging of roll-your-own (RYO) papers be marketed only in a standardized design. In both markets, legislators have chosen a drab brown-green color for all packaging and a predetermined typeface for the brand names. Designs or logos aren’t permitted anywhere on the package. Israel also requires a health warning in Hebrew on RYO paper booklets.

Tobacco Reporter spoke with Christian Hinz, managing director, and Lisa Esser, head of corporate affairs and business development, at Gizeh Raucherbedarf, a German manufacturer of RYO and make-your-own (MYO) papers, about the implications of the extended legislative requirements on their business.

Founded in 1920, the company has 600 employees and is best known for its brands Gizeh and Mascotte. Gizeh, which is present in more than 80 markets, is the only company in the RYO/MYO papers sector that has its own printing plant as the company puts a lot of emphasis on the sophisticated, appealing packaging of its products.

The state-of-the-art print shop at Gizeh’s headquarters in Gummersbach is equipped with three die cutters to produce the elaborate packaging designs of the company’s products, including the firm’s well-known magnetic lock booklet. Packaging development takes place either in-house or in collaboration with specialized agencies.

Tobacco Reporter: In which of the two countries is it easier for manufacturers to implement the new packaging requirements?

Christian Hinz: Definitely for Canada. Health Canada defined 24 months ago that rolling papers, although they don’t contain any tobacco, are tobacco products. Since Nov. 9, 2019, manufacturers and distributors have not been allowed to produce, sell and distribute noncompliant products and packaging. There is, however, a transitional period of two years. Besides, the new rules have been communicated clearly by the Canadian government.

Israel, by contrast, passed its plain packaging law in January 2019. To make their products compliant, manufacturers to date only have a nonauthorized English translation of the Hebrew legal text, which they received at a very late point. The new legislation will enter into force on Jan. 8, 2020. If any merchandise with noncompliant packaging is found at a shop after that date, both the retailer and the manufacturer will be fined up to €50,000 ($55,137). There is no grace period. We have stopped delivering noncompliant products to Israel as retailers cannot guarantee the complete sell-off by the due date.

What does it mean for your product portfolios in these markets?

Hinz: We are only present with one variant of our rolling papers in Canada, but in Israel, we have been selling three qualities of rolling papers in four versions until now. With standardized packaging, you cannot communicate the differences between the individual variants anymore. Therefore, we will have to reduce our offer in Israel to only one product from January since consumers won’t have a chance to differentiate. This is annoying.

Lisa Esser: We first had the idea to include some explanations inside the booklets, which would have reached consumers after they had bought the product, but even that is not permitted, which is incomprehensible to me.

Which implications do regulations like these have on the overall market?

Esser: It will lead to the multinationals taking over an ever-greater share of the market as already is the case in the foodstuff industry. As a result, the selection of different products will decrease. Transferred to tobacco products in, for example, Israel, it means that manufacturers who until now had, let’s say, 20 different products on the market will drastically reduce their portfolio because it’s not economically viable to offer so many variants.

Price will become the only determinant for retail sales figures. This might lead to the formation of an oligopoly that goes straight down the supply chain. Only those manufacturers that can sell their products at a low price and also have a functioning distribution system will be successful.

What about the consumer?

Hinz: The consumer won’t have much of a choice anymore. It is, in a way, an incapacitation of the consumer. We expect a slow process in which the consumer starts to downtrade, following the argument that if there is no difference between the products on offer anymore, they could also buy the cheapest one. The entire process will lead to a deterioration of product quality in the market—at the expense of the consumer.

What do these plain packaging laws mean for you as a manufacturer?

Esser: It’s basically an expropriation of the brand owner as it deprives manufacturers of their intellectual property rights. I still cannot comprehend how constitutional states can permit such regulation. There’s a whole range of implications: We cannot communicate innovations to consumers anymore. It also won’t be possible to launch a small volume of a new product that has proven successful in another country to test it in such a market.

We will probably have to restrict our geographical radius of market activities if there was a domino effect of plain packaging being extended to rolling papers in more markets. There would definitely be a limitation of our product portfolio in countries with plain packaging and/or warning requirements. In the worst case, we would have to launch a dedicated plain packaging variant for each country—just think of the individual health warnings required in the national languages. We expect each market to develop its own standards for such regulation. This would imply a strong individualization and customization of our products, restrict our portfolio, lead to smaller volumes and higher cost.

What effects do you expect the measures to have on counterfeiting?

Hinz: The black market for rolling papers is likely to thrive under such conditions, similar to what happened to the cigarette markets in countries that introduced standardized packaging. This is disadvantageous for all stakeholders in a market. Legislation doesn’t take issues like that into account at all. Forging of rolling papers already is a big problem, but currently the hurdles are high for counterfeiters—if you as a manufacturer continuously launch paper and packaging innovations, counterfeiters’ work gets more difficult. Lawmakers implementing plain packaging lower that hurdle considerably.

How large are the Canadian and the Israeli markets for rolling papers, and what developments do you anticipate for your business following the introduction of plain packaging for RYO paper products?

Esser: The legislative changes in both countries have quite an impact on our business. It’s still too early to say how the situation will develop, though. Assessing the true market size for rolling papers in Canada is very difficult because most of the tobacco cultivation for RYO and MYO takes place in the Native American reservations between Canada and the U.S., which are exempt from taxation. The latter is the basis for a determination of market sizes. In Israel, evaluation of the market is similarly difficult.

What’s your view of current regulation of tobacco products in general?

Hinz: Principally, we have to deal with a lot of poorly crafted regulation today. Take Belgium and France as an example where legislation demands that cigarette paper needs to be matte white. What did lawmakers want to say? Cigarette paper is not permitted to come in colors. If you look at unbleached paper, though, it is gray. Legislative statements like this create uncertainty instead of clarity.