Does it make sense to ban single-use cigarette filters as lawmakers in New York state have proposed?

By George Gay

Earlier this year, my wife and I took a short holiday in a small village in South Devon, U.K. We had a great time—thank you for asking—but there was one disturbing aspect to the break, so readers of a delicate disposition might want to skip the following sentence and move straight to the next paragraph. On arrival, we discovered that the operators of the village’s only pub, which is renowned for its cask ales and food, had to close it for a month, including during the week we were there!

Consequently, we spent more time than we otherwise might have done fossicking about on the beach, which is three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) from the village down a gently sloping valley. The beach was small—no more than 200 yards or meters at its widest point at high tide, but I couldn’t help noticing that in with the considerable amounts of seaweed strewn about there was a lot of foreign matter.

Now I have to be careful here. In saying foreign matter, I would not like to give the impression that I have signed up with the Brexit supporters who managed, despite being in a minority, to winkle the U.K. out of the EU, out of what must be one of the most progressive experiments ever undertaken in international cooperation. No, I remain an unrepentant “Remoaner”—or, in the view of some of our more rabid little-Englanders, an “enemy of the people.” When I say foreign matter, I mean matter that shouldn’t, in a well-ordered society, be found on a beach, whether it is local or from other sources.

I was interested in this foreign matter because I often read stories about how cigarette butts make up high proportions (measured in the number of pieces, I think, rather than in respect of volume, weight or mass) of the litter found on beaches and elsewhere, so I took a closer look. In fact, I didn’t see any cigarette butts, and the vast majority of the litter I did see, whether measured in pieces or volume, seemed to comprise flotsam and jetsam. I also looked in the large container at the back of the beach where community-minded villagers place such material and, again, almost all the debris seemed to comprise items thrown or lost overboard by those on commercial or pleasure ships and boats.

Banning single-use filters

Of course, mine wasn’t a scientific survey, and I have little doubt that if I visited the same beach in the summer when people were sitting on it, the result would be different. Indeed, I am keenly aware that carelessly discarded cigarette butts comprise a huge problem that is causing much damage to the environment, and, in this regard, I was interested in returning home to read a report from Jan. 17 in the Democrat and Chronicle about a proposed bill (Tobacco Product Waste Reduction Act) aimed at banning, from Jan. 1, 2022, the sale in New York state of single-use cigarette filters, whether fixed or attachable (and single-use e-cigarettes). According to the story, the central claims made by the bill’s sponsors were that “filters on cigarettes do not make them any safer and only do damage to the environment.” They were said to comprise a polluting form of litter.

Such comments, which have been made many times in the past, cannot be dismissed. In fact, the environmental objections to filters are undeniable, and I think it would be a brave person who is willing to say, categorically, that cigarette filters make smoking tobacco less risky than it would otherwise be. Additionally, it has been argued in the past that filters give smokers a false sense of at least partial protection and therefore undermine attempts at quitting.

In researching this piece, I perused a few scientific papers to which my attention was drawn, but I did not read anything that would lead me to conclude that there was no doubt that the addition of filters to cigarettes definitely improved health outcomes for smokers. I have to add a number of caveats here, however. I am not a scientist, and I did not read the papers from start to finish. In addition, the papers seemed to have been primarily concerned with comparing the toxins in the mainstream smoke of filtered regular and “low-tar” cigarettes. They did not specifically compare unfiltered cigarettes with filtered cigarettes.

Importantly, given the New York state proposal, the papers I read seemed to throw no light on whether the level of risk that an individual smoker faces is determined by the volume of tobacco smoke she inhales over a lifetime of smoking, no matter the tar or constituent level of the smoke she inhales, given the current range of such tar and constituent levels or whether it is determined by the tar or constituent level of the smoke she inhales each time she smokes. Or, put another way, I’m still no wiser as to whether a person who smokes 20 filtered cigarettes daily that each deliver 4 mg of tar faces the same smoking-related risk as another person who smokes five unfiltered cigarettes daily that each deliver 16 mg of tar.

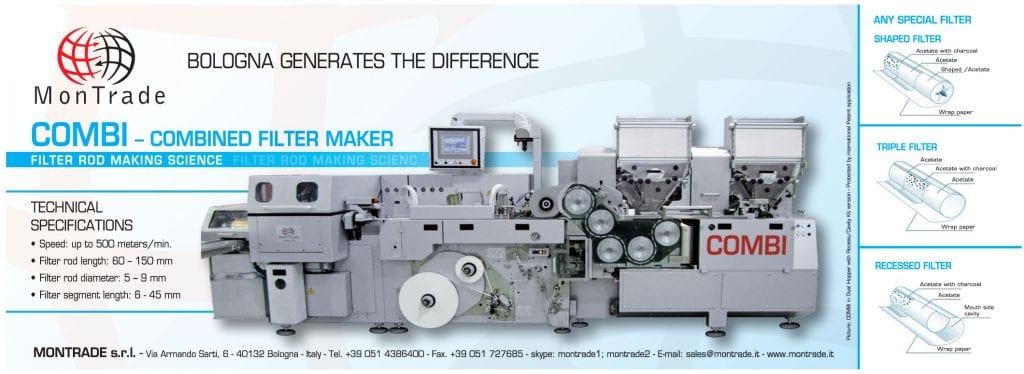

One other point is that I am reliably told that acetate filters are designed and constructed to retain, in respect of given products, specified amounts of the tar and nicotine that would otherwise be delivered as part of the mainstream smoke as measured by standard testing machines. And there can be no doubt that such filters do protect or partially protect smokers from some toxic chemicals. There are, however, at least two problems with this idea, as far as I can see. It seems that because of the complexity of the chemistry of burning tobacco, it is not possible to link lower toxicity with lower risk until, that is, you get down to no toxicity. And there seems to be a tacit admission of this in the multiplicity of filters available. If risk were known to be reduced significantly by using a particular filter that took out certain or certain levels of a known toxin or toxins, all manufacturers would surely use that filter—if not on moral grounds then because of the fear of being prosecuted, notwithstanding competitive pressures.

Counterintuitive

Nevertheless, there is a problem here for those supporting this bill. My overall reading would be that while the science doesn’t support unreservedly the health benefits of filters, it certainly doesn’t support the health benefits to smokers of removing them. Are the bill’s supporters so convinced of the lack of health benefits of filters that they would be willing to ban the sale of filtered cigarettes, something that has been suggested but not acted upon in the past? Without cast iron evidence, surely, as has been said many times before, discouraging the use of cigarette filters is just too counterintuitive; the status quo is just too comfortable. I mean, look at the goo that is present in a filter after a cigarette has been smoked. Surely it is better that the goo remains in the filter and does not pass into the lungs?

Well, I suppose that depends on how you look at things—from the point of view of the individual smoker or society at large. (Those of a delicate disposition might like to skip the next sentence too.) Looked at from the perspective of society in general and the environment in which it exists, it might be better that the goo is filtered only through a human body before being evacuated as part of the smoker’s waste products than held by an acetate filter from which it can presumably leach into the environment directly.

Of course, it is important not to get carried away with the idea that banning cigarette filters would help the environment. With an unfiltered cigarette, the tobacco rod acts as a filter of sorts, and when the end of such a cigarette is discarded, it will also contain leachable goo, though probably not as much as that in a bespoke filter. (There is a way to overcome most of this problem, but I doubt that many lawmakers would try to legislate that smokers should be made to smoke their cigarettes right to the bitter end, holding the last morsel with a clip as is superbly demonstrated by The Dude in The Big Lebowski.)

A more powerful argument against filters, in my opinion, is one that is made less often. Without any evidence, I would suggest that filters, especially those used to help reduce tar deliveries to the low single figures, are complicit in helping young people take up smoking. A first cigarette without a filter must be a vastly different experience to a first cigarette with a filter that delivers only 1 mg or 2 mg of tar. If all that is available to you are unfiltered cigarettes, you really have to work at getting to like smoking, and this, of course, has implications when considering population-wide as well as individual health outcomes.

Responses

This brings us to another couple of points: What would be the reaction of cigarette manufacturers and consumers to the proposed ban, which would apply only to sales in New York state? Presumably, manufacturers would be willing to put on the market only those unfiltered products already available. Given that the major tobacco manufacturers are trying to encourage tobacco users in the direction of smokeless products of various types, they would surely be reluctant to divert investment resources toward putting new unfiltered cigarettes through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s premarket tobacco product application (PMTA) process.

Presumably, while New York state was alone in requiring unfiltered cigarettes, manufacturers would concentrate there on marketing roll-your-own and make-your-own tobaccos, and, more likely, on their next-generation smokeless products. This would presumably open up opportunities for black market operators bringing in and selling filtered cigarettes illegally to the detriment of local retailers and tax revenues. While another business opportunity would be available to anybody who could develop easy to use, multi-use and “effective” filters.

And what would consumers do? Perhaps they would get used to unfiltered cigarettes or multi-use filters, or perhaps the switch to such cigarettes, especially if combined with a switch to low-nicotine tobacco, would be the final straw, and they would quit, in which case the legislation would have been successful in one regard and would be taken up by other states. But they could bring in filtered cigarettes from elsewhere, I suppose, paying the appropriate duties or buy them from black market operators.

What this will come down to, surely, is not the health of smokers because that is in dispute. And it is not primarily about the biodegradability of the filters because the faster they degrade, the faster the toxins they contain will be released. If the environment is to be protected, which is the main concern here, filter butts need to be disposed of properly, at which point biodegradability might become an important secondary issue. I believe that a number of companies are putting considerable efforts into the proper disposal and biodegradability of butts, but those efforts need to be stepped up several gears if this is to remain a voluntary undertaking. It has been a work in progress for too long. I’m certain that it won’t have been missed by the legislators and their advisers in New York state that the idea of developing self-extinguishing cigarettes was always such a work in progress until legislation put a rocket under that project.