To break through globally, the concept of tobacco harm reduction must still overcome lots of challenges.

By Stefanie Rossel

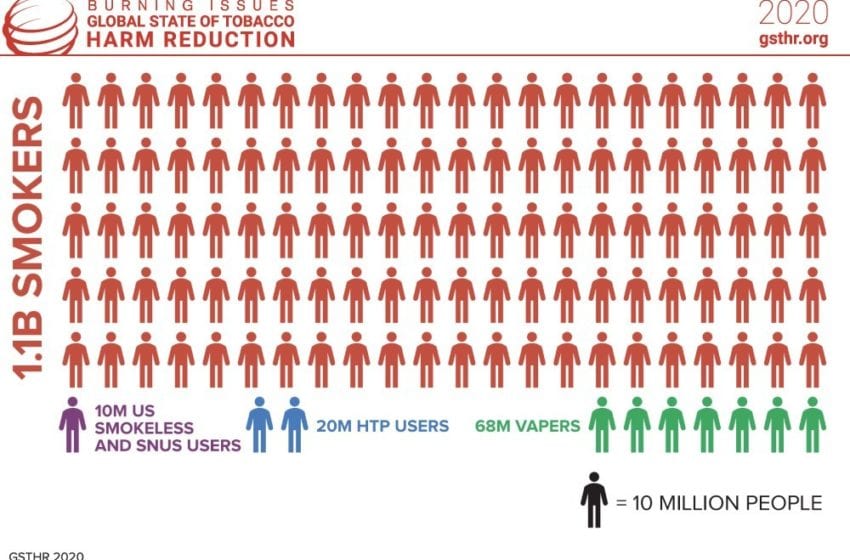

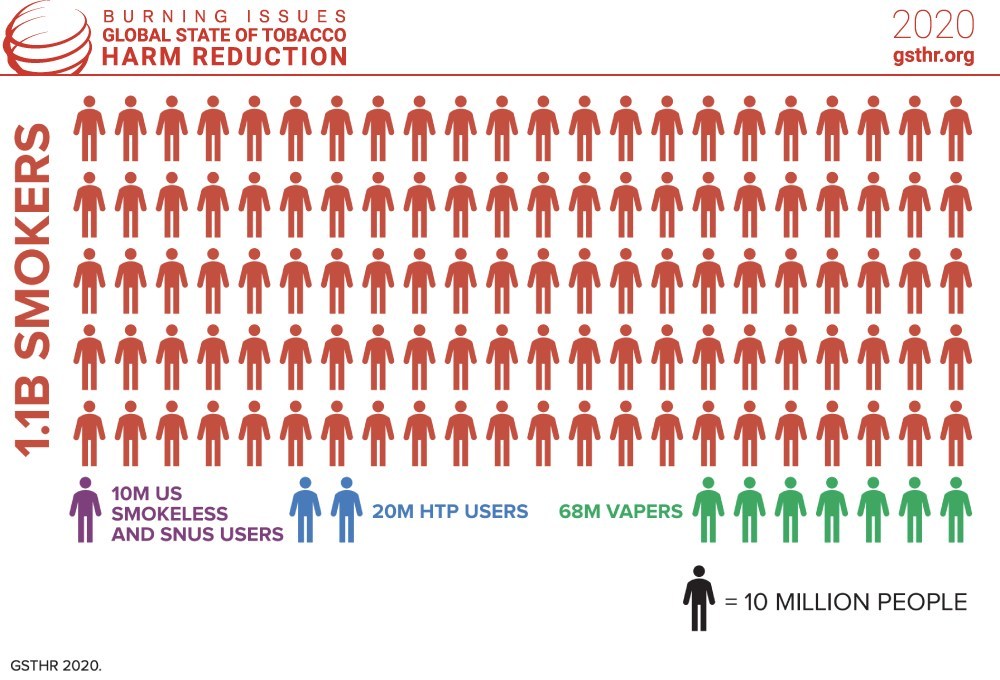

The figures sound impressive: Globally, 98 million people have switched to safer nicotine products (SNP), according to the report Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (GSTHR) 2020, which was published by Knowledge Action Change (KAC) on Nov. 4.

Yet the data look less glorious when put into perspective. With 1.1 billion smokers worldwide, there are only nine SNP users for every 100 smokers. And most of them are in high-income countries, with 68 million vapers living in the U.S., China, Russia, the U.K., France, Japan, Germany and Mexico. Around 20 million people, mainly in Japan, use heated-tobacco products (HTP) whereas 10 million are U.S. smokeless or snus users.

“The two years since the last edition of this report have been a very difficult time for tobacco harm reduction [THR],” said lead author Harry Shapiro. “The estimated 1.1 billion smokers around the world deserve a better deal and better options. We need to hasten the demise of combustibles and encourage the use of safer noncombustible ways of using nicotine. Evidence from several countries shows that the availability of SNP helps people to switch from smoking.”

There is an urgent need to scale up THR, the report insists. Despite billions spent by governments and the World Health Organization (WHO) on tobacco control, the number of smokers has not declined for the past two decades, and it is estimated to remain unchanged until the end of the century, which is a poor result for public health efforts. THR, the report claims, is a human right, and this is particularly disregarded in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC), where tobacco control measures are often poorly or partially implemented. Eighty percent of tobacco users live in LMIC, with meager means to deal with tobacco-related consequences and the least access to affordable SNP.

These countries also tend to have comparatively high levels of smoking, and poor and marginalized groups are disproportionately affected, with an estimated 8 million people dying due to smoking-related disease each year. In 22 LMIC, 30 percent or more of the overall adult population are smokers. While smoking prevalence in developed countries has decreased in recent years, the rates of decline in LMIC have slowed or smoking prevalence continues to grow, often due to population growth.

While SNP clearly provides a solution at almost no cost for governments, many regulators have legislated against such products. Thirty-six countries have banned the sale of nicotine vapor products, among them Australia, India, Thailand and Turkey. Interestingly, Uruguay, which in 2013 became the first country to legalize cannabis, prohibits vapor products. Three countries have lifted their vapor product bans since the first GSTHR report was released in 2018, but this is offset by new restrictions, such as flavor bans, in several U.S. states in the wake of the 2019 EVALI crisis, which was mistakenly attributed to licit nicotine vapor products.

Vapor products are currently regulated in 75 countries whereas 85 countries have no specific laws or regulations on nicotine vapor products (one country, Bhutan, prohibits the sale of all tobacco products, although it has suspended its ban for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic to deter illegal sales). HTPs are marketed in 51 countries but banned in 13 countries. Snus can be legally bought in 81 countries but is banned in 39 countries, including those of the EU, which permits snus only in Sweden for cultural reasons.

Vested interests

Remarkably, the greatest obstacle to SNP is the WHO, according to the report, which meticulously investigated the health body’s funding sources.

Billions of dollars come from well-funded anti-tobacco organizations, most notably those run by Bill Gates and Michael Bloomberg. Their networks of foundations, among them the University of Bath and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, are actively supporting campaigns against THR, thus influencing decision-making at the WHO.

They are aided by foundations supported by the pharmaceutical industry, which fears losing revenue from their nicotine-replacement therapies to SNP. Finally, among the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FNTC) members are 17 signatories with vested interests in the continuation of combustible cigarette consumption: governments that own stakes of at least 10 percent in tobacco companies. Through its tobacco monopoly, China alone was responsible for 38 percent of the world’s cigarette volume in 2017.

The spread of SNPs has also been slowed by the initial lack of scientific data. However, this has massively expanded to more than 6,300 scientific publications, mostly on vaping. In the meantime, misinformation has proliferated due to flawed science and a lack of knowledge about less-hazardous nicotine products among medical doctors. Politicians who don’t comprehend the technology and science behind THR have added to the problem while the consumer’s voice is often ignored in policymaking.

Critical for LMIC

Assessing comparative harms of nicotine-delivery products has become the basis of THR science. In 2014, David J. Nutt, a British psychiatrist and psychopharmacologist, developed a test to define the harms of different nicotine products. Combustible tobacco products are the most harmful. “Apart from the health issues caused by consumption, cigarettes are responsible for most fires in the world,” said Nutt. “There is a high product-specific and a product-related morbidity as well as high economic cost. The impact beyond the user is enormous.” Snus, with its much lower impact overall, is at the other end of the scale, which has come to be known as the continuum of risk.

Harm reduction has proven its value in other fields, such as alcohol and drug abuse, Nutt pointed out. He said opposing THR might well be the worst example of scientific denial since 1616 when the Catholic Church banned the works of Copernicus and denied ongoing research findings for 150 years. “If the WHO doesn’t accept the concept of THR, its credibility is at stake,” said Nutt.

During the GSTHR launch event, three experts shared their firsthand experiences in LMICs. While Africa has applied the concept of harm reduction in many sectors, such as HIV prevention, SNPs continue to face an uphill battle, according to Chimwemwe Ngoma, a tobacco harm reduction advocate in Malawi.

Many LMICs are insufficiently resourced to implement THR strategies. Besides, they rely on flawed public health information. In most LIMCs, SNP are banned or taxed so heavily that they become unaffordable. In Malawi, the cheapest e-cigarette costs $75 whereas combustible cigarettes sell from as little as $0.50 per pack, according to Ngoma. “Millions of people shouldn’t be denied access to products that can help them avoid poor quality of life, disease and premature death,” he said. An alternative to make THR more affordable in LIMCs, Ngoma added, would be snus.

Mwawi Ng’Oma, program manager for St John of God Hospitaller Services in Malawi, also attributed the lack of progress to limited research, capacity and resources. “There is a lack of research concerning substance use and misuse, including tobacco and THR, in most LMICs,” she said. “Central systems for the collection of data don’t exist. There are also only inadequate addiction recovery services to support current smokers willing to switch.” Furthermore, tobacco smoking is socially accepted in some African cultures and commonly used in certain ceremonies, likely making it difficult for people to accept THR measures. Health priorities in the region, she concluded, are mainly on communicable diseases.

The situation is also dire in India, a country with 120 million smokers, second only to China in terms of tobacco consumption. Most combustible tobacco is consumed in the form of bidis, hand-rolled, inexpensive cigarettes that contain more nicotine, carbon monoxide and tar and present a greater risk of oral cancers than conventional cigarettes. In addition, India has about 200 million users of smokeless tobacco. Contrary to snus and modern oral products, Indian smokeless is very deadly. India’s oral cancer rate is the highest in the world.

In 2019, India banned vapor products nationwide. Samrat Chowdhery, founder-director of the Association of Vapers India (AVI) and president of the International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organizations (INNCO), spoke about the ban’s impact on consumers and the economy. “Implementation of FCTC measures is generally low, but governments follow WHO guidance,” he said. “In most countries with a ban on vaping products, they are meant to ‘save the country’ but result in the emergence of black markets.”

A decisive year

Although the FCTC aims to protect present and future generations from the damages of tobacco and smoke, it has largely ignored the potential of THR, according to Marina Foltea, founder and managing director at Trade Pacts, a Swiss-based trade and investment consultancy.

“The FCTC has focused on supply and demand, on taxation, packaging, labeling, illicit trade, the prevention of sales to minors and alternative crops to tobacco rather than harm reduction,” she said. “The original wording of the treaty doesn’t mention SNP because these products arrived later on the market.”

The Conference of the Parties (COP) started talking about SNP much later, basing its discussions on scientific reports commissioned by the WHO, such as a recent one that described banning SNPs as a legitimate regulatory approach despite findings that they are less harmful than cigarettes. The most recent COP session, which took place in 2018, only took stock of what member states do about THR and gave recommendations. Presently it seems that the WHO has expressed support for THR only in medical form. Consultations have been put on hold because of the pandemic.

The next COP, scheduled for November 2021, is likely to be influenced by the recent SCHEER report, a scientific review on the health effects of e-cigarettes prepared for the European Commission in preparation for the 2021 revision of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). However, scientists have criticized the report as fundamentally flawed as it contradicts commonly acknowledged scientific evidence on vapor products.

Other factors expected to influence the COP include Brexit—Public Health England appears to be more cautious now on their liberal approach to SNP—the 2019 U.S. EVALI crisis and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) modified-risk approvals of Swedish Match’s General snus and Philip Morris International’s IQOS heat-not-burn product.

Potential ways out

Although highly important, the consumer has been conspicuously absent as a voice in the THR debate. “The discussion seems to be dominated by two men [Bloomberg and Gates] who buy governments around the world and are driven by advisers who give them the wrong idea of what THR is,” lamented THR advocate Martin Cullip.

By commissioning scientific studies with preconceived results that are widely published, the “philanthrocapitalists” create insecurity among consumers while misleading media reports lead to harmful policy, according to Cullip. “There is a massive imbalance in power and influence,” he said. “Consumers have to continue to stand up and raise their voices and fight against these people.”

Politicians should start listening to unbiased scientists, said Fiona Patten, leader of the Australian Reason Party. In Australia, she noted, politicians had banned vapor products based on the wrong assumptions, including fear for children’s safety and the involvement of Big Tobacco. Instead, Patten said, politicians should ask where the products should be sold and to whom. “Instead of asking ‘Is it safe?’ they should ask ‘How can we reduce harm?’ and ‘What are the experiences of the people who have lived this?’” she said. “Those are the questions asked in all other areas of harm reduction efforts.”

Clive Bates, director of The Counterfactual, called for a better understanding of how THR works. “We need more mindfulness of the pervertedness of disproportionate regulation and replace it with a story that is more helpful. We need to be less liberal on more-harmful and more liberal on less-harmful products regarding, for instance, taxation or advertising,” he said. “And we need a deep rethink of nicotine as a popular consumer drug that could have its place like caffeine.”

Instead, everything is being done to degrade less-harmful products, to create barriers to the entry and to make the transition from smoking to vaping less attractive. “As a consequence, we will see more smoking, black markets, more home smoking and a lot more harm,” said Bates.

To counter misinformation, Philippine PR practitioner Jena Fetalino recommended getting the THR story shared as widely as possible. Scientific evidence, she said, is the best offense and the best defense because experts are more trustworthy than prohibitionists. “Consider media as an ally rather than an enemy,” she suggested. “Remember social media can magnify your voice, and consistency is the key.”

A stony path

Burning Issues says the primary aim of tobacco control should be to offer smokers suitable exit strategies. The WHO should encourage FCTC signatories to take a more balanced view of SNPs to help encourage a switch away from combustibles while consumer well-being should be at the center of international planning and policy. Governments should hasten that switch instead of preventing it, and no action should be taken that favors smoking over SNPs.

Hurdles, however, remain high, especially with the philanthrocapitalists’ funding of anti-THR strategies. “This is not simply a question of equally valid differences in scientific interpretations,” Shapiro told Tobacco Reporter. “The evidence in favor of safer nicotine products is clear and consistent. These products are substantially safer than cigarettes; they offer a realistic off ramp for people who want to switch away from smoking while they are not a gateway to smoking for young people,” he said.

“Unfortunately, this science is being contested by a public health narrative, which is morally based in a refusal to accept recreational use of nicotine and an entirely bogus claim that the whole SNP enterprise is literally a smokescreen by Big Tobacco to get kids hooked on nicotine to compensate for falling sales, at least in higher income countries,” Shapiro added. “It’s hard to see how you combat a belief system with actual evidence, but we have to keep trying and hope to push anti-tobacco harm reduction elements onto the wrong side of history.”

While THR is specifically mentioned in the preamble of the FCTC, Shapiro sees little chance of forcing the organization to include THR in its strategy through legal measures. “The reason [THR] is there is that the architects of the FCTC back in the 1990s actually sat down with industry who were making some attempts at producing safer products. The problem was that they all involved combusting tobacco so were never going to work as safer products,” he said.

“Even so, the idea of THR was written into the FCTC as there was another declaration that the FCTC would keep up with the scientific evidence. The implication was that should there be viable SNP developments, then they would become part of FCTC strategy,” Shapiro said.

“However, once new products became available, the WHO completely reneged on this commitment and instead insists there are ‘irreconcilable differences’ between public health and the industry. I doubt there are any ways to force the WHO to change its stance—but bear in mind that the FCTC is only a framework convention, not a treaty. This allows signatories maximum latitude over regulation and control, unlike the EU TPD, which is legally binding.”

THR’s prospects are also not great for the upcoming TPD revision, judging by the tone of the recent SCHEER report, according to Shapiro. “Negative comments by EU health officials on World No Tobacco Day earlier this year concerning SNP and the fact that the EU works hand-in-glove with the WHO based in Geneva all point to a hardening of approach in the next iteration of the TPD,” he said.

Flavor bans proposed in the Netherlands, Denmark and Belgium would exacerbate the situation for THR, Shapiro explained. On the positive side, the FDA’s MRTP approvals for General snus and IQOS may set a precedent against which THR opponents will have to justify unwarranted regulation. “It opens the door to the idea that there is now some official acceptance that these products can be marketed as safer than cigarettes,” said Shapiro. “It is also a recognition that it is possible for industry science to successfully make the THR case.”