New to the tobacco product industry? There are some things you need to know about past industry behavior that affect how U.S. regulators treat you.

By Cheryl K. Olson

I was finishing my doctoral studies at the Harvard School of Public Health when this headline hit the newsstands: “Tobacco Chiefs Say Cigarettes Aren’t Addictive.” It was April 15, 1994.

The New York Times opened its coverage with, “The top executives of the seven largest American tobacco companies testified in Congress today that they did not believe that cigarettes were addictive but that they would rather their own children did not smoke.” My professors shared studies showing that children could recognize Joe Camel (a then-ubiquitous cartoon cigarette spokesperson) as easily as Mickey Mouse.

I shared this memory with a colleague of mine, who joined Big Tobacco as a newly minted Ph.D. in 1998, hoping to make a difference with modified-risk products. That year, the Master Settlement Agreement was upending decades of freewheeling industry practices.

“Companies had been saying things like, ‘No one knows the mechanism for how cigarettes cause disease,’” he recalled. “And we still don’t know the mechanism. But that’s not the point. The point is cigarettes cause disease. With a relative risk of 15, they are the cause!” He described the tension created by his company “transitioning to, and being honest and open with, that truth.”

If you’ve dealt with the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products, you’ve seen the term “grandfathered.” Tobacco products marketed as of Feb. 15, 2007, are “grandfathered,” or not affected by new rules, and don’t need authorization to stay on store shelves.

My colleagues in public health, medicine and science who are middle-aged or older might be said to have “grandfathered attitudes” about companies that sell nicotine products. These attitudes were shaped by years of exposure to industry bad behavior, recalled from advertising, news coverage and academic articles. Whether you’re coming to the tobacco industry fresh from university, transferring in from another field or starting a company meant to disrupt and transform how people consume nicotine … congratulations. To the eyes of public health, you wear the modern face of that old villain, Big Tobacco. The history of industry misbehavior is now your history too. When people hear you speak or see your products, marketing materials or research, they’ll assess everything in the context of that history.

Based on two decades working with evolving tobacco technologies and regulations, toxicologist Willie McKinney shared this advice: “If you’re going to disrupt tobacco, because of all the baggage, you’ve got to know the history. Because it’s still nicotine. And still addictive.”

Here are some examples of how yesterday’s misbehavior affects you today.

Misuse of research and statistics

The 1954 advertisement “A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers,” signed by the heads of 14 companies and associations, is a landmark of the industry’s disingenuous promises and misuse of science. Claims include “Distinguished authorities point out that medical research of recent years indicates many possible causes of lung cancer” and “We believe the products we make are not injurious to health. We always have and always will cooperate closely with those whose task it is to safeguard the public health.”

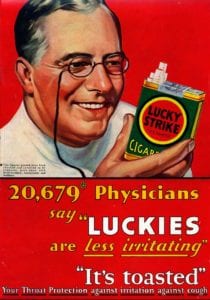

In his 2020 TEDx Mid-Atlantic talk, “The Past, Present and Future of Nicotine Addiction,” Center for Tobacco Products Director Mitch Zeller includes the famous 1930s advertisement showing a physician with a white coat and whiter teeth smiling at a pack of Lucky Strikes. The ad reads: “20,679* Physicians say ‘Luckies are less irritating’” and “Your Throat Protection against irritation against cough.” The asterisk points to a statement assuring that “the figures quoted have been checked and certified to” by an auditing firm.

This misuse of the trappings of science colors how industry research is perceived today. McKinney served for three years as the industry representative on the FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC). He recalled with frustration that when FDA staff presented data to the TPSAC, “They would have a little asterisk by any references or papers that were published by the tobacco industry. That’s why I gave a talk once called ‘Life Without the Asterisk.’ Because FDA always seemed to have to call out, ‘this is a paper published by them.’”

‘Safer’ cigarettes that weren’t

Be sensitive to the history of products touted by the industry as technical advances in safety or pathways to quitting. Zeller’s talk mentioned two such safety snafus. In the 1950s, the innovative Kent Micronite filter turned out to be lined with asbestos. In the 1960s and 1970s, the “light” cigarette was a bust.

In the transcript of the January 2018 IQOS TPSAC meeting, member Gary Giovino shared his personal experience with this: “I’m 35 years past cigarettes … but I relapsed a couple of times because I thought light cigarettes were safer, and we know now that that’s not true.”

As it turned out, tar and nicotine levels were indeed lower when a machine “smoked” the cigarette but not when a human blocked the ventilation holes with his lips and fingers. From the industry’s perspective, the machine numbers were meant for comparative analyses, but their use in advertising was perceived as deliberately deceptive.

As the Center for Tobacco Product’s website states, “FDA’s traditional ‘safe and effective’ standard for evaluating medical products does not apply to tobacco …. There is no known safe tobacco product.”

Denial or trivializing of addiction

Oh, that indelible front-page image of tobacco company executives, right hands in the air, being sworn in before Congress: seemingly swearing that cigarettes aren’t addictive! Industry testimony in the 1980s and 1990s tried to muddy the waters by mentioning addictions to coffee, television, tanning and (my weakness) chocolate. In 2005, some major companies’ websites were still waffling, saying smoking is addictive “as commonly understood today” but not “in the same sense as heroin [or] cocaine.”

Denial of marketing to youth

In the 1960s, U.S. companies adopted voluntary codes to keep cigarettes away from minors nearly identical to some used today: No models who look younger than 25. No celebrity testimonials with youth appeal. No samples to persons under 21.

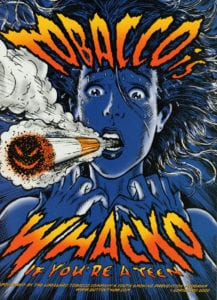

Purported anti-smoking ad campaigns (Lorillard’s “Tobacco is whacko if you’re a teen!”) were colorful, creative and attractive. Researchers poring over millions of pages of industry documents made available through litigation (see tobaccoarchives.com) found ample evidence of industry targeting the historical age of starting smoking. For example, one 1989 internal market research report stressed the strategic importance of young replacement smokers, noting that only one in three smokers started after age 18.

Menthol/marketing to minorities

Industry documents showed that menthol cigarettes were perceived (and marketed) as healthier. They appealed especially to Black Americans and inexperienced young smokers. This helps explain the sensitivity to claims about flavors.

The Responsive Chord

Picture a public health researcher at an FDA meeting. He’s listening to an industry scientist present data on the addictive potential of her company’s product. But to him, what she’s communicating goes beyond her words or the images on her slides. When her message strikes his existing mental storehouse of tobacco industry science and lore, it creates in his mind what media theorist and advertising guru Tony Schwartz1 called a “responsive chord”—sensory impressions that provoke a predictable emotional response. The meaning of the communication is not found in what the speaker conveys; rather, the meaning is created when her listener combines her message with his existing emotions and knowledge.

To avoid triggering negative stereotypes and suspicions, be mindful of the history above when presenting to regulators. Stick with the science and the data. Don’t refer to products as “safe” or “safer.” Avoid phrases like “we believe that …” which echo those deceptive “frank statements.” Rather than pledging to market responsibly to adult consumers, provide details of how you will verify age of purchasers and monitor and respond to any underage sales.

Be especially mindful of reactions by reviewers from outside the FDA, such as TPSAC members. Center for Tobacco Products staff often rotate in from jobs as chemists, project managers or lawyers at other centers at the FDA and (as one put it to me) “don’t really have a horse in the race.” Rather, their loyalty is to their profession. Outside reviewers are more likely to have spent their careers in tobacco control and to have more “responsive chords” when it comes to tobacco science.

1 Schwartz T. The Responsive Chord. How Media Manipulate You: What You Buy, Who You Vote For, And How You Think (2nd Ed.) Coral Gables, FL: Mango Publishing, 2017. (First edition published by Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1973.)