Tipping papers serve both functional and aesthetic purposes. Not only do they help ensure the integrity of the rod-filter construction and play a role in cigarette ventilation, but they also provide useful real estate for decorations. Using sophisticated printing and embossing technologies, manufacturers can appeal to senses of sight and touch. For this article, Tobacco Reporter interviewed two prominent industry suppliers about their innovations relating to tipping papers.

What you see is what you feel—the growing interest in embossed tipping papers

It is always interesting when opportunities are identified and exploited within business sectors, such as the traditional tobacco products market, that are, overall, less than vibrant. It seems to indicate that somebody, a team perhaps, or even a whole company, has been thinking outside the box—or, in one case at least, thinking big inside the box.

Toward the end of last year, the Tann Group told Tobacco Reporter that for the past five years it had been enjoying a “tremendous” increase in interest for embossed tipping papers—an increase that had required it to make major investments in machinery and personnel to keep up with demand. And it seems that, for at least three reasons, this increase in interest is likely to be maintained. One is the vital feedback loop that is powered by consumer demand and that is clearly working hard in this case. Another is that while the increase in demand has been widely spread, it has not gone global—yet. And yet another is that, working within the letter and spirit of even strict regulations, cigarette manufacturers can use some embossed tipping papers to help maintain the attractiveness of their products even when and where those regulations are being imposed so as to reduce product appeal.

But more of that later. Firstly, it is necessary to explain for those not already familiar with embossing as it applies to tipping paper, something about the types of embossing that are available for such applications, which comprise macro-technology, micro-technology and nanotechnology. Macro-embossing delivers a haptic effect, one that doesn’t require any special surface treatments of the tipping paper, such as printing or coatings, and that is experienced by a smoker through her fingers and lips because the bosses produced by this process, which are in the submillimeter range, are large enough for them to be detected by touch. By contrast, in the case of both micro-embossing and nano-embossing, the surface deformations produced are respectively within the micrometer and nanometer ranges, which are too small to be detected by touch but which interact with visible light and in this way provide some spectacular visual effects.

In the case of micro-embossing, the structures produced influence the reflection of visible light, so this technology is used only on tipping papers that have metallized surfaces, such as those produced by metallic hot foil stamping, and not on plain paper. Without micro-embossing, the light reflected by stamped hot foil items, such as lines and logos, would be clear and shiny as it would be when reflected by polished metallic surfaces. But with micro-embossing, the light reflection becomes diffuse and scattered as it is on matte metallic surfaces, and this gives the hot foil designs a satiny appearance.

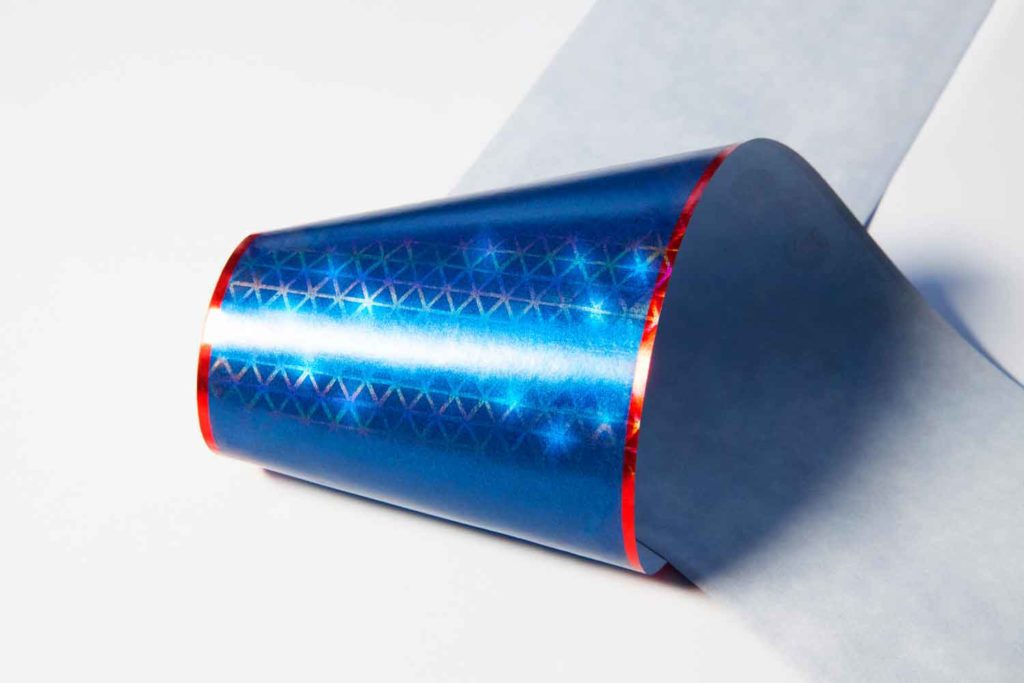

The nano-embossed structures, meanwhile, cause the light that strikes them to be diffracted in such a way as to produce an interference effect—to be split into the spectrum of colors and thereby to deliver rainbow visuals, holographic impressions and the “tilted image” effects that are strongly dependent on the angle at which they are viewed. Nano-embossing, which requires the tipping paper to have a full-surface color, produces its strongest effects the darker that the background color is.

Of the three types of embossed tipping paper on offer, the Tann Group says it is the macro-embossed one that is currently most in demand because it communicates with consumers on both a haptic and a visual level, something the company describes as a “what you see is what you feel” concept. But it is the case that embossed tipping papers, whether they employ macro-embossing, micro-embossing or nano-embossing, are used mainly on premium brands, partly because of the haptic and visual upgrades they provide but also simply because of the higher prices that such tipping papers command.

It follows, then, that embossed tipping papers, whether macro-embossed, micro-embossed or nano-embossed, are particularly popular in those places where premium brands are most in demand, including duty-free outlets. Currently, demand for embossed tipping paper is mainly coming from the countries of the CIS and Asia, including China and South-East Asia, but it is expected that the trend will move to parts of Europe and Central and Latin America.

Of course, due to stricter regulations that will govern tobacco products in the future, including those imposed through the EU’s second Tobacco Products Directive, it will become more and more difficult in certain regions to apply to tipping papers special features, such as special inks, aromas/flavors and metallic elements. However, embossing technologies—and especially macro-embossing—provide potential options to maintain the appeal of tipping papers while complying with such regulations, because no extra chemical treatment of the tipping paper or application of special inks is required. With the help of purely mechanical converting of tipping papers, there will still be opportunities for effective design upgrades that do not come into conflict with regulatory or sensory/toxicological restrictions.

Given the importance of maintaining product appeal while complying with regulatory requirements, it is worth mentioning, too, that the embossing techniques described here can be applied also to printed paper inner liners, which is the first point of interaction, contact and, therefore, communication that the consumer has with a brand after opening a pack of cigarettes.

Examples of off-the-shelf macro-embossed, micro-embossed and nano-embossed tipping papers are available from the Tann Group, which also offers a design service as part of development projects in which customers get to see and feel the finished product prior to a market launch. —George Gay

Into the Void: The Fine Art of Cigarette Ventilation

Thinking recently about the perforation of cigarette tipping paper, I was reminded that Leonardo da Vinci is credited with once having said that among the great things that are found among us, the existence of nothing is the greatest. I’m sure you can see where this is leading. The perforation of tipping paper allows for the controlled dilution of tobacco smoke, so, given that in many parts of the world, controlling the deliveries of tobacco smoke constituents is the subject of government regulation, it is no overstatement to say that perforating technology plays a vital role in cigarette manufacture. And so here is a case where a vital role is played by perforations—holes if you like, and what are holes if not nothing?

Of course, this introduction is somewhat misleading because, in the case of perforations, the nothingness “created” is defined by the material in which they are made—the tipping paper, though it is still the case that some such papers are not perforated.

But in the main they are. Axel Nather, head of sales and marketing at Micro Laser Technology (MLT), told Tobacco Reporter in an email exchange early this year that a few manufacturing processes still used electrostatic perforation, which worked well where only very low levels of ventilation were required. However, he said, as government regulations and end users demanded cigarettes with increasingly lower deliveries, laser perforation was ultimately the solution. Laser perforation could be used to produce very stable low-ventilation, medium-ventilation and high-ventilation levels, and ventilation level adjustment was very simple, requiring only changing the hole sizes, track numbers and hole quantities.

With MLT systems, the operator can instigate these adjustments, and, in the case of online equipment, additional parameters can also be set, so, for example, thicker cardboards can be perforated or cut.

The use here of the word “cut” needs some explanation as does the reference to “online” equipment. When it started in business 20 years ago, MLT developed and supplied offline laser perforation machinery, but during the past 10 years, it has also been offering and supplying online equipment. This means the company has three main groups of tobacco industry customers comprising cigarette manufacturers of all sizes, paper converters and machine builders that integrate MLT’s laser equipment into their production lines.

Offline machinery, which comprises stand-alone machinery, is almost always supplied directly to customers. On the other hand, online equipment can, as stated above, be taken up by manufacturers when MLT’s equipment is fitted to OEM cigarette making machinery, and it can be retrofitted to existing manufacturing lines either by MLT or by specialist rebuilders. And finally, there are laboratory systems, which, Nather said, could be delivered with many technically exciting elements.

Finally, that is, in relation to perforation machinery and equipment. The tobacco industry also uses MLT’s systems for laser cutting and laser scribing, mainly in the production of cigarette packaging, where cardboard and foils are cut and scribed. But MLT’s laser perforating and cutting systems have come into their own with the rise of heat-not-burn (HnB) products. Mostly, HnB products are made with relatively thick materials, such as cardboard, said Nather, so for this reason, MLT had developed laser systems that could generate extremely short pulses of very high powered lasers. This allowed the creation of very small, clean holes, and it also meant that many thousands of “cardboard sticks” could be perforated per minute. And if the speed was still not sufficient, two lasers could be used simultaneously to double the speed.

All this adds up to what Nather described as a pleasing and increasing level of project inquiries and sales, despite the fact that in 2020 the coronavirus pandemic had had a significant impact on the entire tobacco industry, with projects often being delayed. Nather mentioned in particular steadily increasing inquiries in the area of online perforation and HnB products. And he said MLT’s service department was currently very busy because, in part, it now maintained older laser systems produced by other suppliers and refurbished their laser sources.

One of the reasons that Nather gave for the increasing level of interest was the innovative nature of the tobacco industry, especially in the area of new product developments, for which MLT’s laser systems were often needed. “This is, of course, very gratifying; development projects are always a great pleasure when exciting products are created,” he said. “As a medium-sized company, we are very flexible and can react relatively quickly.”

The one challenge Nather mentioned concerned the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, and I asked him what difficulties MLT had faced and what steps it had been able to take to ameliorate those difficulties. Some tobacco industry projects had been postponed and others had taken longer than normally would have been the case, he said, especially during 2020 and early 2021. In addition, travel had been difficult, and, in some cases, it had not been possible to enter some countries, such as the U.S., for a relatively long time.

In response, MLT had created the circumstances whereby systems could be put into operation virtually, often by helping customers through webcam-based remote maintenance. Interestingly, Nather added that while MLT was glad traveling had become easier again, it would continue to use or even expand the possibilities offered by online maintenance and commissioning. —George Gay