A glimpse at patent registrations shows what the future of tobacco harm reduction may look like.

By Stefanie Rossel

Since the first filter cigarette was manufactured in 1934, the cigarette has stayed more or less the same. Despite some tweaks to filters, papers and tobacco blends over the decades, innovation was not exactly the word that came to mind in the context of combustible cigarettes. So it’s little wonder that when the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was drafted in the late 1990s, its authors could not imagine a future product much different from the familiar tobacco column wrapped in paper. As a consequence, the FCTC makes little to no reference to intellectual property or technology.

The past two decades have proven the FCTC creators—and many other observers—wrong. While the WHO was trying to cut down tobacco consumption with classic strategies, such as tax hikes, smoking bans and health warnings, a new generation of reduced-risk products, including e-cigarettes and tobacco-heating devices, entered the market. Many of these products bore little resemblance to the combustible cigarette that the FCTC was designed to tackle.

Developed by independent entrepreneurs, the first vapor products surprised the tobacco industry as much as they did their WHO counterparts. After realizing the potential, however, cigarette manufacturers redirected some of their formidable resources at developing the sector, creating a multitude of new reduced-risk technologies.

In recent years, the leading tobacco companies have pumped billions into research and development to offer their customers smoke-free alternatives. Philip Morris International alone had invested $9 billion in R&D by 2019. Median R&D expenses stood at $495 million for the fiscal years ending December 2017 to December 2021. They peaked in December 2021 at $617 million.

BAT has spent more than $2.6 billion on R&D investment since 2012. In a preliminary statement in February 2022, the company said that it had further increased next-generation products investment by £496 million ($653.44 million) in 2021.

Japan Tobacco International invested $2 billion between 2015 and 2020. The efforts are likely to pay off not just in terms of having less risky products available but also financially. Euromonitor expects the global retail value of the reduced-risk category to exceed $100 billion by 2025, up from $40 million in 2020.

A Different Strategy

As technology investments increase, intellectual property is becoming more valuable—and contested, as demonstrated by the recent PMI/Reynolds American Inc. dispute. In September 2021, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) ruled that PMI’s IQOS heated-tobacco product (HTP) infringes on two RAI patents. After the Biden administration failed to intervene, PMI and its U.S. partner, Altria Group, were barred from importing IQOS devices in the U.S.

The case is charged because IQOS is currently the only electronic nicotine product with a modified-risk tobacco product (MRTP) designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which allows Altria to market the product with reduced exposure information. Among other things, the company may tell consumers that its heating system significantly reduces the production of harmful and potentially harmful chemicals compared to conventional cigarettes. The ITC ruling means that American smokers currently don’t have access to IQOS. PMI is now looking at manufacturing IQOS in the U.S.

Unlike the WHO, the FDA, which was authorized to regulate tobacco products by the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Control Act, acknowledges that electronic nicotine-delivery system products are fundamentally different from combustible cigarettes, and the agency has provisions to accommodate reduced-risk products.

To receive MRTP designation, a manufacturer must provide scientific evidence showing that its product is “appropriate to promote the public health” as defined by the FDA. Although criticized as a long-winded and costly pathway—PMI handed in more than a million pages of documentation to support its IQOS application—the process at least offers a prospect for reduced-risk products, which is more promising than the WHO’s “quit-or-die” attitude.

Innovation in the Making

Tobacco and vapor companies’ substantial R&D spending is reflected in the number of tobacco harm reduction (THR) patents. Between 2010 and 2020, an estimated 73,758 patents were published globally in the areas of nicotine vapor products, smokeless nicotine products and HTPs, according to the 2021 Patent Landscape Report, a study prepared by Oxfirst Managing Director Roya Ghafele for the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.

Established tobacco companies, such as PMI, BAT and the China National Tobacco Corp. (CNTC), hold the largest patent portfolios in the THR space, showing that the development of less hazardous nicotine-delivery systems is a priority in their strategies. In terms of patents published, nicotine vapor technology is the fastest-growing THR technology, with a compound annual growth rate of 9.1 percent. It is followed by heated-tobacco technology, which has been growing 4.1 percent per year, and smokeless tobacco technology, which has a 1.1 percent annual growth rate.

Geographically, patent publications are concentrated in high-income or upper-middle-income countries. Companies operating in the tobacco and cannabis sectors dominate patent activity: In tobacco-heating technology, CNTC, PMI and BAT account for 15 percent of patents published in the past 10 years. China leads with an estimated 22,956 patent publications followed by the U.S. with an estimated 14,344 publications. In the Africa and Middle East region, patent activity remains limited to Israel, Morocco and South Africa, according to the report. In nicotine vapor technology, the picture is similar: About 10 percent of all patents granted during the past decade are held by CNTC, PMI and Kimree Hi-Tech, a Chinese e-cigarette manufacturer.

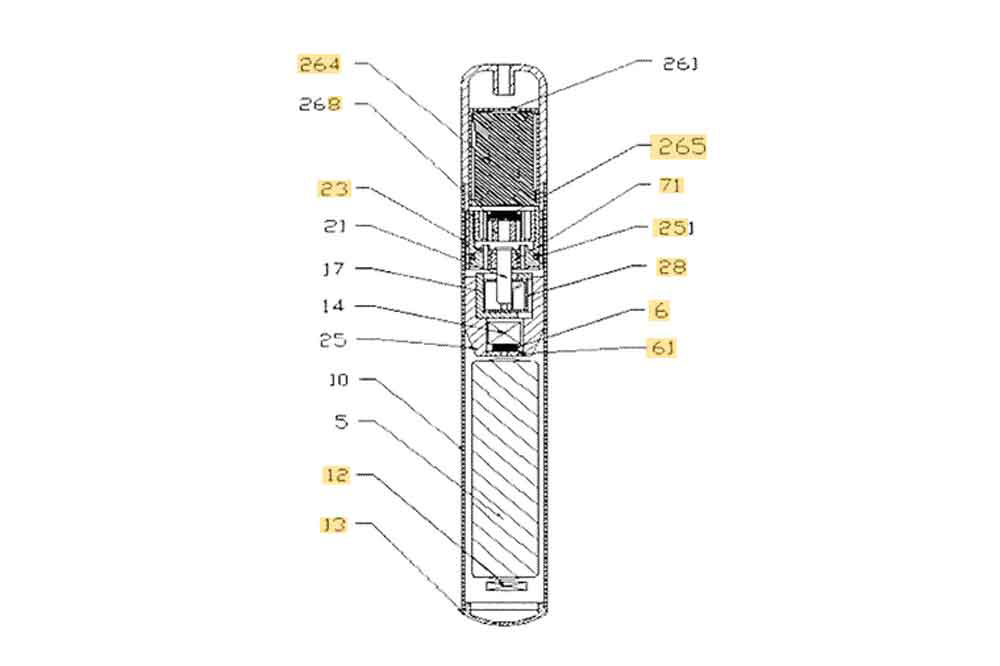

(Photo: Respira Technologies)

Toward Therapeutic Uses

The patent filings provide a glimpse into what the future of THR might hold. Interestingly, the number of patents for nicotine vapor technologies that could result in medical smoking cessation devices or be applied to other therapeutic purposes has increased substantially over the studied period. Between 2010 and 2020, 48 percent of patents were filed under classifications related to medical or veterinary science. According to the report, this indicates a shift from recreational technology toward more therapeutically oriented technology. While many patents currently focus on the vaporization of cannabinoids instead of nicotine, there is also mention of other therapeutic drugs, including those targeted at relieving pain, fever, inflammation and disorders of the nervous system.

As far as the hardware is concerned, the number of patents referring to sprayers or atomizers adapted for therapeutic purposes ranks second behind those for inhaling appliances shaped like cigars, cigarettes or pipes.

Patents relating to electrical heating or constructional details, such as the connection of cartridges and battery parts, also represent a large part of publications. BAT’s Pure Tech development is an example of this trend. The ultra-slim, micro-engineered stainless steel distiller plate acts as both the heater and wick, replacing the traditional coil and wick system and thus optimizing the aerosol process so that there is less risk of thermal breakdown in products. In its Science & Innovation Report 2020–21, the company calls Pure Tech a game-changer. Laboratory tests show that the vapor generated by this technology contains around 99 percent fewer and lower levels of certain toxicants compared to cigarette smoke, according to BAT. In biological tests, cells exposed to this vapor exhibited a much lower response or no response at all compared to cigarette smoke, a result that strongly suggested that this technology could contribute to the reduced-risk profile of its vapor products, BAT said.

PMI has filed patents for vaping technology that includes sensors that are designed to monitor the characteristics of their users and provide therapeutic data, according to the Patent Landscape Report. Should these devices make their way into consumer nicotine products, Ghafele concludes, this would shift the purpose of these products from purely recreational to therapeutic, making nicotine businesses potential partners for insurance companies, public health authorities and other related industries. It could also further normalize—and improve access to—reduced-risk product technologies.

While the patent publications by nicotine companies indicate a “pharmaceuticalizaton” of these industries, patent filings by pharmaceutical companies active in nicotine-replacement therapies suggest that these players remained focused on pharmaceutical uses for nicotine and are uninterested in entering the recreational nicotine space.

Reserved for High-Income Countries

In heated-tobacco technology, Ghafele found, most patents related to the design and manufacture of devices with an emphasis on the heating element, which tobacco companies seek to improve to increase the efficiency of their technology. BAT’s current Glo HTP range is heated by induction technology, thus avoiding direct contact between the electronics and the heating element. JTI’s Ploom S and Ploom X HTP models, by contrast, work with the company’s proprietary HeatFlow technology, where a ribbed heat chamber heats the tobacco stick from the outside for minimal charring.

Following the blade-heating technology employed in initial generations of IQOS, PMI has added induction to heat the tobacco in its latest generation of HTP devices, IQOS ILUMA, which launched in 2021. The company’s TEEPS HTP platform, meanwhile, uses carbon-heating technology. The device works without electronics. It features a charcoal tip that is lit to produce heat. In the charcoal tip, oxygen reacts with the carbon in a combustion process, producing heat and carbon dioxide. An aluminum disk separates the charcoal from the tobacco, transferring the heat but blocking the airflow, thus preventing the tobacco from reaching the ignition point.

Of the HTP patents analyzed by Ghafele, 38 percent were filed under therapy-related codes. The frequent mention of antineoplastic agents, which are medications used for cancer treatment, could indicate that companies are researching these agents to reduce the health risks of their products, she notes. There was also high patent activity relating to the therapeutic use of nicotine for neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease.

While the report suggests that the once-staid tobacco industry has evolved into a highly innovative sector, it also reveals a shortcoming: Few of the patent applications are filed in the developing world, where intellectual property protections tend to be weak. Given that most smokers live in low-income and middle-income countries, this represents a missed opportunity for tobacco harm reduction.

To bridge the gap, says Ghafele, stakeholders should explore ways to better integrate the needs of developing countries and motivate tobacco companies to offer potentially less harmful products outside of the wealthy world.