The availability of nicotine with minimal harm justifies a complete rethink of our approach to this legal recreational drug.

By Clive Bates

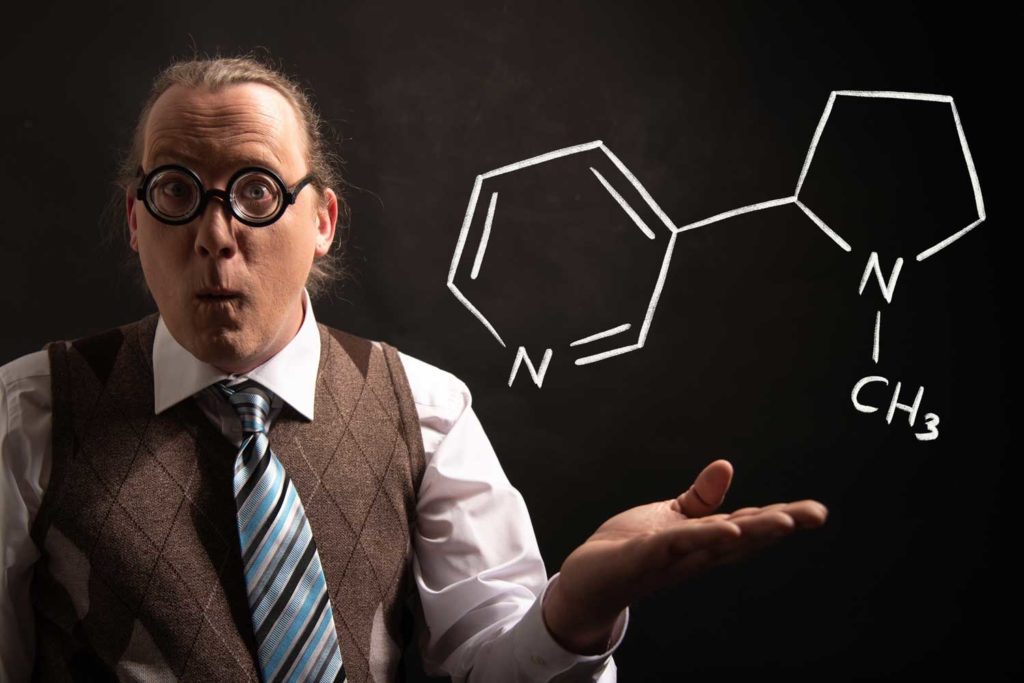

Whisper it quietly, but people use nicotine for a reason. Nicotine has psychoactive effects that provide functional benefits and pleasurable sensations to its users. Neal Benowitz, a global authority on nicotine, writing in the U.S. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology in 2009, summarized the effects: “In humans, nicotine from tobacco induces stimulation and pleasure and reduces stress and anxiety. Smokers come to use nicotine to modulate their level of arousal and for mood control in daily life. Smoking may improve concentration, reaction time and performance of certain tasks.”

Writing in the journal Nicotine & Tobacco Research in 2018, the neuroscientist Paul Newhouse described the cognitive benefits of nicotine: “Cognitive improvement is one of the best-established therapeutic effects of nicotinic stimulation. Nicotine improves performance on attentionally and cognitively demanding vigilance tasks and response inhibition performance, suggesting that nicotine may act to optimize attention/response mechanisms as well as enhancing working memory in humans.”

With such characteristics, one is tempted to ask why nicotine has so few users. It turns out this is a serious question with some interesting implications. The answer is that nicotine use is strongly associated with the harms of smoking and an addiction so powerful that former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop compared it to heroin or cocaine. The iron grip of nicotine addiction keeps people smoking even though they are well aware of the lethal consequences.

Nicotine seems to provide valuable benefits for people whose lives are difficult and stressful, those prone to anxiety or distraction or those who just enjoy the strange mixture of its stimulating and calming effects. Perhaps that could mean most of us? At one point, it did. In the decades before the health implications of smoking were widely understood, smoking prevalence was very high. In the United Kingdom in 1948–1952, smoking prevalence was about 80 percent for men and 40 percent for women. That compares to a combined total of around 14 percent today. But the overwhelming driver of this decline has been intense concern about harm to health and the introduction of policies to reduce these harms by making smoking less appealing, more expensive and more difficult to do. But maybe our concerted public health efforts to reduce disease and death caused by smoking deterred people who would otherwise have benefited from or enjoyed the mood-regulating and cognitive benefits of nicotine had it been available in safer forms.

So, here is the interesting question. What if nicotine use is no longer all that harmful? What if the real problem was always the inhalation of toxic smoke while trying to consume nicotine for its benefits? As early as 1991, the leading medical journal The Lancet reflected on how the nicotine landscape might look after the year 2000: “There is no compelling objection to the recreational and even addictive use of nicotine provided it is not shown to be physically, psychologically or socially harmful to the user or to others.”

In my view, we have reached the position where smoke-free nicotine products, such as e-cigarettes, heated tobacco, smokeless tobacco or nicotine pouches, can provide nicotine at acceptably low risk. By acceptably low risk, I don’t mean perfect safety, but within society’s normal risk appetites for consumption and other recreational activities. If continuing innovation in the design of the products ultimately leads to smoking cigarettes becoming obsolete, then the vast burden of smoking-related disease will decline and fade away.

So why is there so much opposition to low-risk nicotine products? Why do so much effort and money go into trying to demonstrate that these products are harmful? I call this the weirdness of harm, and it takes several forms.

First, perhaps good science shows these products are very harmful and should be treated no differently than cigarettes? We can rule out this explanation quite easily. The toxicants found in users’ blood, saliva and urine are far fewer, and the levels are far lower than in smokers. Credible data show a range of benefits in switching from smoking to smoke-free products, and there is little convincing evidence to suggest material risks at present. We might be concerned about currently unknown long-term effects, but these are more likely to be trivial than severe and may be tackled if and when they emerge, which they haven’t so far. Yet the ferocity of the backlash against safer products goes far beyond doubts about safety or concern for the welfare of consumers. It looks more like a reaction to a threat.

Second, much safer products pose an existential threat to a powerful interest group. As a profession, tobacco control exists only because of a need to control severe harm to health. A significant part of the professional tobacco control field could ultimately be rendered irrelevant and unemployed by safer forms of nicotine. The whole edifice of careers, grants, university departments, journals, conferences, advocacy campaigns and the personal prestige of anti-tobacco warriors has harm as its foundation. Otherwise, it becomes the equivalent of “coffee control,” which barely exists. That creates strong, perverse incentives to find (or fabricate) harms to sustain the profession. That conflict of interest is large and pervasive, yet it is paradoxically invisible and never acknowledged or discussed. But for many, it means good news is unwelcome, and bad news is good news. Take, for example, the muted reactions to the recent sharp decline in U.S. teen smoking compared to the apparent enthusiasm that has greeted the long list of (unfounded) scares about nicotine vaping, such as e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury, popcorn lung and seizures.

Third, without harm, the case for a nicotine-free society falls apart. Harm is the primary reason for abstinence from nicotine. Gallus and colleagues found that about 80 percent of smokers quit because they currently experience harm, expect harm in the future, have taken a doctor’s advice about harm or worry about harming others. Only 2.8 percent mentioned “loss of pleasure or desire to smoke.” But if the products are no longer harmful, where does that leave those who feel we should aspire to be a “nicotine-free society”? That goal likely arises from a mixture of motives: a loathing of the tobacco industry and a sense that “harm reduction” is an unfair escape from its inevitable destruction, an instinctive disgust about the drug choices of others or just the stoical sentiment that if people can be abstemious, they should be. Harm has always been the trump card of the proponents of a nicotine-free society, but their case is greatly diminished if it rests mainly on moral instincts.

Fourth, it is possible that nicotine use will increase without the deterrent effect of harm. This arises from a basic but unsettling economic argument. The underlying demand for nicotine was once very high but has been suppressed by harm to the user and related policies. The harms of smoking are part of the overall nonmonetary costs (health, stigma, welfare) of using nicotine to the individual. Low-risk products and proportionate regulation will reduce or eliminate these costs. All other things being equal, lower costs mean that nicotine use should increase. Many will be uncomfortable with the prospect of nicotine use rising after years of sustained decline. But we should recall that the effort to reduce nicotine use was driven by the harms of smoking not by opposition to the effects of nicotine as a drug. If we successfully address the public health goal, these smoking-related deterrence effects will no longer apply.

Fifth, harm is integral to the definition of addiction. The casual and sloppy use of the word addiction is pervasive in public health. It is always worth asking what is meant by “addiction.” In the formal Addiction Ontology, serious harm is integral to the definition of addiction: “A mental disposition toward repeated episodes of abnormally high levels of motivation to engage in a behavior, acquired as a result of engaging in the behavior, where the behavior results in risk or occurrence of serious net harm” (emphasis added).

The inclusion of serious net harm in the definition of addiction is intended “to limit the class to things that merit a treatment and public health response.” A similar reference to harm is also included in other definitions, such as those of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse and the American Psychiatric Association. So, it could be argued that without the associated harm from exposure to smoke, nicotine would no longer be classified as addictive and would simply join the short but growing list of psychoactive chemicals people enjoy and society accepts, like caffeine, alcohol and increasingly, cannabinoids. C. Everett Koop’s 1988 comparison of nicotine to heroin was a powerfully provocative statement, but in the context of safer nicotine products and the U.S. opioid epidemic, the comparison is not convincing.

The emerging range of smoke-free consumer tobacco and nicotine products means much more than tobacco harm reduction or an elegant way to help smokers quit. The availability of nicotine with minimal harm justifies a complete rethink of our approach to this legal recreational drug.