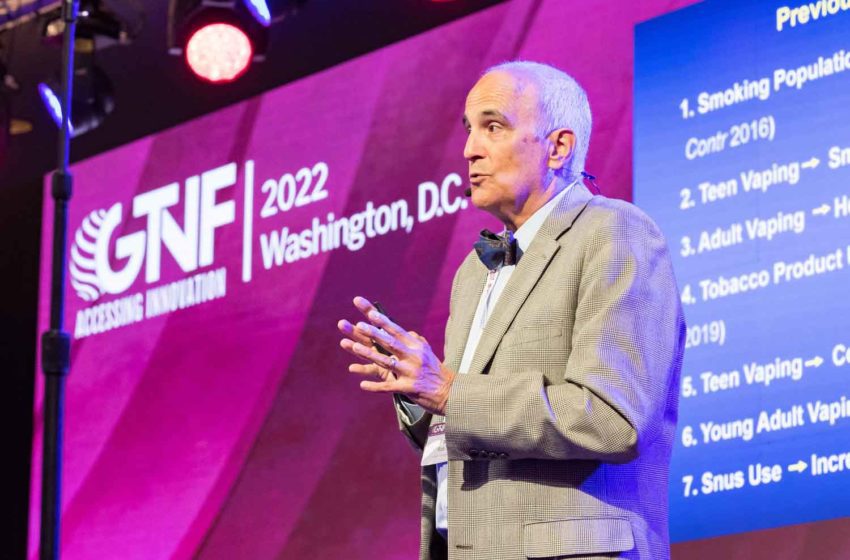

Brad Rodu, a U.S.-based professor working at the University of Louisville Department of Medicine’s James Graham Brown Cancer Center, delivered a short, sharp shock to attendees at the recent GTNF.

His presentation was short, under 10 minutes in length, and therefore, by necessity, sharply focused on what was a shocking message, though one that, in different forms, GTNF participants have become all too used to hearing.

“The mission of a tobacco-free society drives the tobacco control industry, and it is driving bad tobacco science, which is not being addressed either pre-publication by peer reviewers, or post-publication, in any systematic way,” Rodu said at the end of his presentation. “And these … studies, if they are left alone, if they’re not challenged, they are going to deter smokers from switching [from combustible cigarettes to less risky tobacco and nicotine products]. We’ve already seen that, and we’ve had presentations about that. And I believe they will support harsh and unfair regulation.”

That needs some context, which Rodu provided at the start of his presentation when he told his audience that the U.S. federal government’s mission, the focus of its tobacco program, was aimed at creating a tobacco-free society. Under this program, hundreds of millions of dollars were being transferred from the Food and Drug Administration to the National Institutes of Health, and from there to universities around the U.S. for funding research on tobacco products.

The issue here is not that this research is being carried out but the way in which it is being carried out. Rodu said that a lot of the research was beset with problems, and he put up a slide showing a list of studies that he and his team had looked at critically and had commented on formally: reviews that could be found on the websites of the journals that had published the original research or on the websites of other journals. The list of studies was formidable, so he mentioned just a few. His team had looked, for instance, at the finding that the U.S.’ smoking population had been “softening” and that harm reduction was therefore unnecessary, a finding—a suggestion—that would have left many in the audience agape. They had looked, too, at the finding that vaping by teenagers was causing them to smoke, that tobacco product use of any sort was increasing mortality, that vaping by teenagers was related to Covid and that vaping by adults was causing heart attacks …. The last-mentioned finding Rodu described as the most famous one because his team had had that paper retracted.

Rodu then highlighted recent studies that basically claimed to have found that vaping is associated with myocardial infarctions or heart attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, emphysema, other pulmonary disorders, strokes and other medical conditions. In reporting these diseases, the researchers had claimed to have statistically accounted for smoking. But Rodu said these claims were completely unreliable, and he described why.

Rodu and his team found that none of the studies had information about the ages when participants had started smoking, started vaping or when they were first diagnosed with these diseases. When Rodu’s team analyzed the FDA Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health data, which contained this information, they found that all but a tiny percentage of diseases were diagnosed after participants started smoking but before they started vaping. And the small number of people who were diagnosed with diseases about the time they started vaping had all been smokers, making it highly unlikely that those diseases had been caused by vaping.

Rodu said the bottom line was that studies that did not take into account the ages of people when they started to vape and smoke, and when these vapers and smokers became ill, were unreliable.