When it comes to tobacco, the European Commission should abandon its overly complex ideas and embrace some fresh thinking.

By George Gay

The people of England and Wales were advised by health chiefs not to get drunk on Dec. 21—and I think it is worth pausing for a moment to take in the enormity of the implications of that advice …

But, moving on, the reason for the advice’s having been given specifically for Dec. 21 was that ambulance drivers were due to go out on strike that day, which meant it was going to be more challenging than usual to deliver to hospitals those people, drunks and their victims, injured by drunken behavior.

No such advice had to be given in respect of the consumption of tobacco. Those seeking enjoyment through the consumption of nicotine rather than alcohol do not over-consume, and, importantly, do not, as a result of their smoking, lose their faculties for thinking clearly and, like drinkers, start acting in silly, violent and otherwise bizarre ways.

Given this, I feel moved to ask, not for the first time, why it is that, in most parts of the world, and certainly in Europe, about which this story is concerned, tobacco and tobacco consumers are regarded as society’s pariahs while alcohol and alcohol consumers are regarded as being part of the normal social milieu—hail fellow, well met! Why is it that we take seriously people who, while drinking alcohol and becoming increasingly muddled in their thinking, pontificate on, among other things, the evils of tobacco and smoking?

It seems totally illogical, but one answer, I guess, could be that so many people drink alcohol that, collectively, we have passed the tipping point of population-level befuddledness and, consequently, are no longer able to summon the level of critical faculties necessary to see through the inconsistencies and hypocrisies that drive our lives. On the whole, unlikely.

Nevertheless, something weird is going on that defies logical analysis. While the world at large has long been at war with tobacco consumption, the original, often well-meaning objectives seem to have been pushed to one side. The purported reason behind the tobacco conflict, as I understood it, was to reduce the death and disease caused by smoking, but the focus seems to have shifted elsewhere, in part to the defiance of the various methods being used in the conflict, and to a whole string of largely peripheral activities. We are told that there are 1 billion smokers worldwide, but there must now be another billion who owe their livings or part of their livings to anti-smoker activities and/or to devising ways of defending the wasteful expenditure of conflict funds.

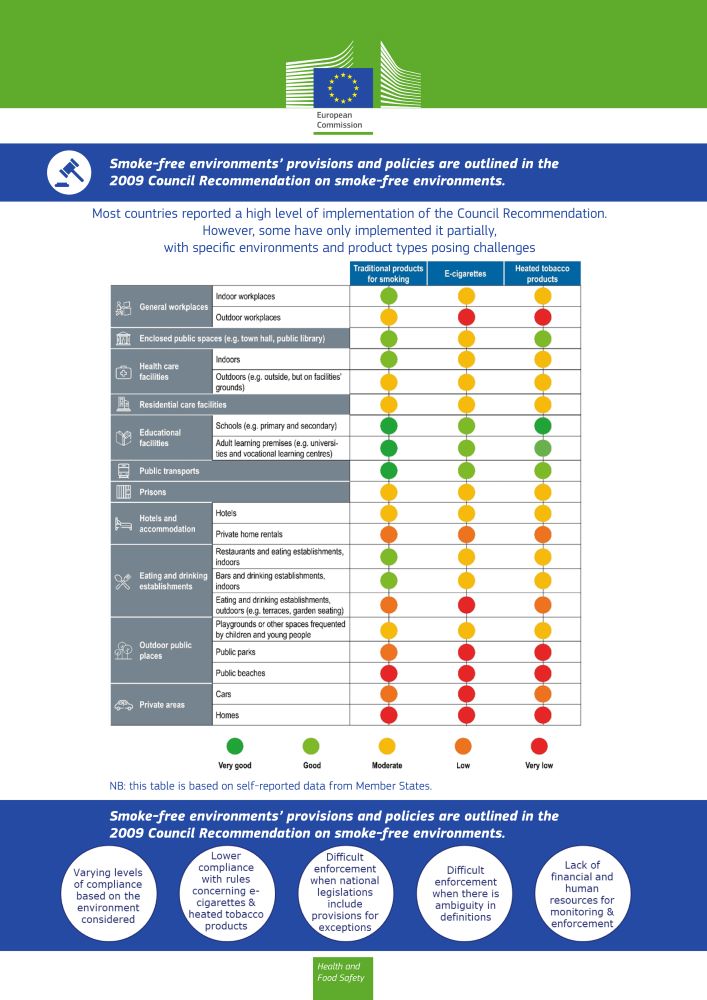

A Curious Leaflet

In June last year, the European Commission issued a curious leaflet that included a table illustrating what, at first glance, seemed to be the overall level, EU-wide, of the implementation of a European Council recommendation on the enforcement of smoke-free and vapor-free environments. In fact, some of the smoking restrictions, including those to do with outdoor areas and private places, and the vapor restrictions, apparently fall outside the remit of the recommendation but presumably within rules in force within some EU states. The left column of the table listed 20 places where, technically, a person could smoke or vape, but, according to the rules, may or may not be allowed to do so. The table had three right-hand columns, one headed “Traditional products for smoking,” the second headed “E-cigarettes” and the third headed “Heated-tobacco products.” Against each of the 20 places, three colored circles appeared, one in each of the right-hand columns indicating whether enforcement was “very good” (dark green), “good” (light green), “moderate” (yellow), “low” (orange) or “very low” (red). So, for instance, enforcement in indoor workplaces, the first of the rows, was indicated to be very good (dark green) in the case of traditional smoking products but only moderate (yellow) in respect of e-cigarettes and heated-tobacco products.

What struck me about the right-hand columns of the table, which, in total, included 60 colored circles, was that it looked like something designed by a child, whiling away a wet Sunday afternoon, innocently unaware that some people have difficulty distinguishing such colors. But, of course, this was something that had been produced by adults paid to do so. It had been funded presumably by the anti-tobacco, anti-smoker money tree, which spares no effort, no expense on even the most peripheral of exercises.

The table seemed so far removed from the coalface of tobacco harm reduction (THR) that I couldn’t understand what purpose it served, but I felt certain that the money it cost could have been better spent. The needle of THR would have been shifted more if the funds needed to produce the table had instead been used to buy 100 or so e-cigarettes or packs of snus that were subsequently handed out to impoverished smokers.

And there was a sinister side to the table. One of the places listed in the left-hand column was designated “private homes,” where enforcement was described as very low (red) in respect of all three products. This raises a worrying question. Does the commission believe that, at some stage in the future, it would be very good if the lights changed to green along this row, indicating that people were being monitored in their homes to determine whether they were smoking or vaping? This is not idle speculation. The commission says in the leaflet that “There is a gap in the legislation of exposure to smoking in multi-unit housing” while acknowledging that “Smoke-free measures are difficult to monitor in private places (for example, homes and cars).”

Of course, the amount of money wasted on the leaflet is probably small, but I suspect there is an awful lot of such ephemera wafting through the halls of the commission, and a lot of small amounts of money can add up to … well, a lot of money. And more is planned, even in these straitened times. The commission says that the 2009 recommendation is limited and that, in part, “There is a need to increase financial and human resources available for monitoring and enforcing rules on smoke-free environments.”

Collective Consumer Intelligence

Nothing could be further from the truth. The commission should pause for thought. When e-cigarettes first became available, they quickly became popular through a system of what I would call collective consumer intelligence, a human version of swarm intelligence in which insects such as bees and ants work together to form efficient societies without the need for management. Early adopters of e-cigarettes went on to the internet and performed waggle dances to indicate where the best e-cigarettes were to be found, and things started to work well. It was only with the intervention of countless managers, including those at the commission, that THR started to slow down.

In fact, one of the proofs of this argument lies with snus rather e-cigarettes. The EU must have spent millions of euros purportedly on trying to get smokers to quit, but it banned snus, except in Sweden. Banning snus has got to rate as one of dumbest policies ever devised, anywhere in the world, in respect of anything. It requires apparently sentient people ignoring the evidence staring them in the face—ignoring the fact that the proportion of smokers in Sweden, which is heading down toward 5 percent, is lower than in any other EU country.

But perhaps it is me who is being dumb in believing that the EU wants to reduce the level of tobacco smoking within its territory. After all, this premise is based on self-reporting. If it is wrong that this is the aim, then its actions become perfectly logical.

Chasing its Tail

The idea that the commission and the EU have lost the plot is supported by the effort they have put, and are putting, into the establishment and operation of a traceability system for tobacco products. Although this effort is aligned with the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products, which came into force in 2018 under the aegis of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, it is not a health initiative. It has nothing to do with seriously trying to stop people smoking but is aimed at providing, in the commission’s words, “member states and the commission with an effective tool that enables the tracking and tracing of tobacco products throughout the union and the identification of fraudulent activities that result in illicit products being available to consumers.” In other words, the huge effort that is being expended to put the system in place is aimed at increasing the sales of licit tobacco by reducing those of illicit tobacco. But you have to ask whether this is a proper use of the commission’s energies, especially in the straitened times we are suffering.

It could be argued, of course, that it is in society’s interest to stop illegal trading no matter what products are involved, but I would counter that, in the case of cigarettes, such efforts merely show the commission to be chasing its own tail. The illegal trade in cigarettes in the EU is fueled by unfair levels of taxation applied to tobacco products by countries, in part at the behest of the commission, so the simple answer is to reduce taxes and do away with the need for a complex traceability system.

And it is complex, as anybody will realize if they read through the commission’s Nov. 3 draft of recommended amendments to the 2018 traceability system Implementing Regulations, which weighs in at 17 pages with 23 pages of appendices. “The traceability system established in accordance with Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/574 started collecting data on tobacco products’ movements and transactional data on 20 May 2019,” the draft says. “Experience in its implementation has further demonstrated the importance of high quality, accuracy, completeness and comparability of the data that need to be recorded and transmitted to the system in a timely manner.

“In its report on the application of Directive 2014/40/EU of 20 May 2021, the commission stressed that the member states and the commission had considerable problems with the quality of traceability data …”

You can imagine where this goes—into a haze of legalese covering the minutiae of tobacco product logistics. None of this helps smokers, but it helps to provide jobs for those in the burgeoning and lucrative trade of making miserable the lives of smokers.

Who pays for this traceability rigmarole, you might ask. Well, according to the commission, it’s very simple. The costs of operating and maintaining the system, and of storing the data, is borne largely by tobacco manufacturers and importers. But you would have to be terribly naive to accept that at face value. The costs purportedly borne by manufacturers and importers will be passed onto smokers, which will increase the financial burden on them and make it more likely that they will turn to illicit products. The system, incomprehensibly, is designed to punish those who buy licit products for the sins of those who buy illicit products. Again, the commission is chasing its tail.

What the commission needs right now is a good dose of simplicity. It should throw out the complexities of traceability, unban snus, stop agitating for a ban on nicotine pouches, stop interfering in the development of the sorts of e-cigarettes and heated-tobacco products capable of persuading smokers to quit their habit, and stop worrying about novel products that might or might not come along.

The collective intelligence of smokers, aligned with the best interests of tobacco product and nicotine product manufacturers, clearly intent on converting the market, will do the heavy lifting. It is time to sweep away the musty, overly complex ideas of the past and let in some light and new thinking.

Yeah, like that’s going to happen in the run-up to the EU’s Tobacco Products Directive III, with the huge number of anti-smoker jobs on the line.