Beyond Face Value

- Also in TR Print Edition

- December 1, 2023

- 0

- 12 minutes read

Applied properly, age estimation technology can be a valid tool to discourage youth access.

By George Gay

One of the most effective arguments available to those opposed to tobacco harm reduction (THR) is based on what they describe as the child vaping epidemic because, no matter whether such an epidemic is occurring, there is no rational argument that can overcome the emotional tug of politicians crying “child vaping epidemic!” as they trawl for votes and attempt to reset their flagging careers.

Of course, children—here taken to mean those under the age at which it is legal to buy vaping products—should not be sold vapes because this is against the law in many, perhaps most, countries. But they are sold vapes—so the question arises as to how this is possible. Well, in the U.K. at least, it is possible largely because many of those politicians now fuming about the child vaping epidemic have, with 13 years of austerity, undermined the effectiveness of public services, including those, such as Trading Standards, that are charged with policing retailing.

In the face of these problems, one of the few hopes the vaping industry has is to try to help bolster the policing of what happens in retail outlets, in part by using age estimation technology. Anybody who listened to the video presentation by Robert Burton, group scientific and regulatory director of Plxsur, which was part of the Bonus Content of the September Global Tobacco and Nicotine Forum in Seoul, South Korea, will have heard him make a case for age estimation technology to be used in stores selling vapes. In fact, such technology is currently being tested in two outlets in Italy run by Puff Store, part of Plxsur, before a planned wider rollout. Puff Store is using Innovative Technology’s MyCheckr system, which Puff Store’s CEO, Umberto Roccatti, described as “an excellent example of how vaping businesses can support vital legislation and responsible business practices through innovation.”

Proper Terminology

But before looking at the MyCheckr system, a little housekeeping is in order. The sorts of technologies in question are sometimes referred to as “facial recognition” or “age verification” systems, but I shall use the phrase “age estimation” because that is how Andrew O’Brien, the product manager at Innovative Technology, referred to it during a conversation with me. I doubt there is much wrong with using the term “age verification,” though, as will become obvious later in this piece, the way the system operates means there is nothing to “verify.” But “facial recognition” I would think is to be avoided, partly because it is misleading in respect of MyCheckr and partly because it would be as well to heed the lesson from the introduction of the electronic cigarette. The word “cigarette” in this phrase established a link in many people’s minds between the new, noncombustible product and the old, combustible product even though there was a world of difference between them; and it is only now, a decade and more later, that the term “vape” is starting to take the edge off this issue. I cannot help thinking that, for the same reason, THR advocates should, from the start, try to avoid the use of the term “facial recognition,” which in many people’s minds is linked, not unfairly, to mass-surveillance—in which Innovative Technology has decided not to become involved—overly intrusive policing, discrimination and human rights abuses.

During a telephone interview on Oct. 23, O’Brien told me that age estimation, as provided by MyCheckr, was different from facial recognition, crucially because the data produced by this device was not capable of identifying a person and therefore was not considered to be “special category” data under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in force in the EU, the European Economic Area and the U.K. In particular, the U.K.’s Information Commissioner’s Office had clarified that processing biometric data for the purposes of the Age Appropriate Design Code could lawfully be done to meet the “substantial public interest” exception in the U.K. GDPR. In practical terms, this means retailers may operate the MyCheckr system for age estimation and may do so without needing to get permission from those entering their stores.

How it Works

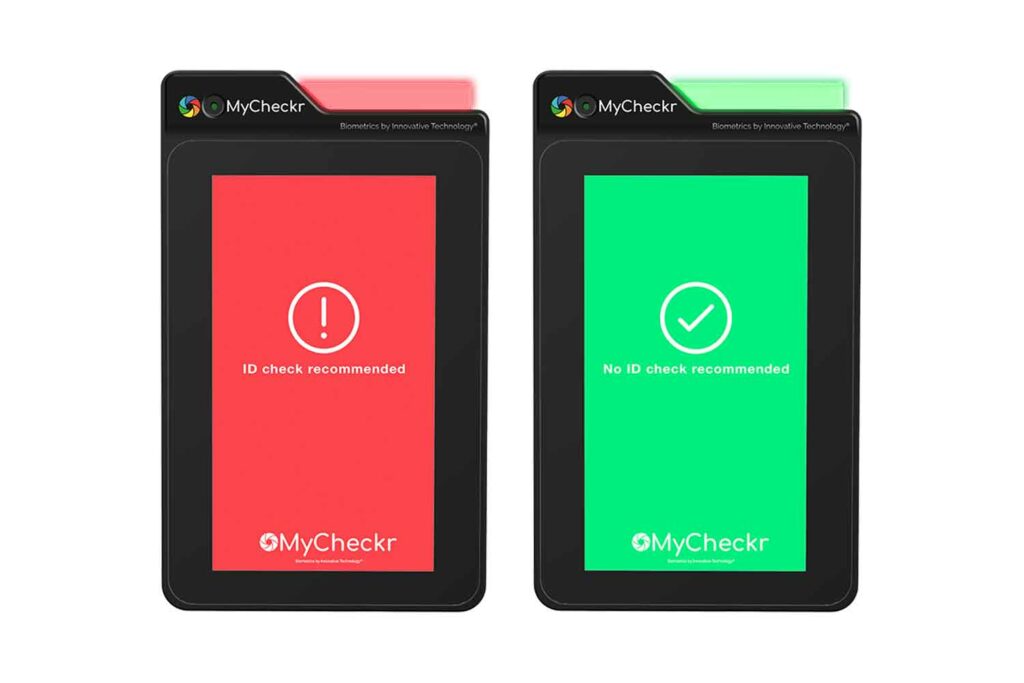

The MyCheckr device is positioned next to a retailer’s till from where it scans the face of anybody who comes within its range, which covers people in wheelchairs and those well over six feet in height—in all, about 98 percent of the U.K.’s adult population. If the system determines the person is more than 25 years of age, a green light shows and the store assistant may sell the customer age-restricted goods, including vapes, while if it determines the person to be under 25 years of age, a red light shows and the assistant is obliged to ask for a form of identification that provides proof that the person is more than 18 years of age.

MyCheckr’s system is based on the use of algorithms that are composed during machine “deep learning” exercises. No, I don’t understand it either, but basically, the machine is presented with millions of facial images of people whose ages are known, and from the particularities of these images it builds a database of age-related facial characteristics. To avoid bias and inefficiency, care is taken during the learning phase to ensure the machine is presented with similar numbers of male and female faces and similar numbers of skin tones, as defined by the Fitzpatrick scale.

Importantly, the machine learning seems to have worked. The MyCheckr was tested in March 2021 under the Age Check Certification Scheme when it was found to have been sufficiently accurate, to be used as part of a “challenge 25” program. The device did not “pass” anybody under 18 as over 25, and, on average, it underestimated the age of 18-year-olds by only 0.19 of a year. Remarkably, perhaps, O’Brien told me his company had improved the system during the year and a half since that test had been carried out. And he also mentioned that the device could now tell the difference between a face and a picture of a face presented either on paper or on a mobile screen.

Privacy Protections

One reason why MyCheckr is not, and could not be, used as a mass-surveillance facial recognition system is that it cannot store the scans it makes of customers’ faces. And since all the processing is done within the device, there is no need for it to be connected to the internet, which means no images leave the device.

Interestingly, the efficacy of MyCheckr in preventing underage customers from obtaining age-restricted products from retail outlets goes beyond its scanning operations. O’Brien said that Innovative Technology had taken part in a trial of an earlier version of the MyCheckr in conjunction with the U.K.’s Home Office, which had wanted to understand how technology could help to ensure people complied with the Licensing Act 2003, covering the sale of alcoholic products. One of the things to come out of the test was that the mere presence in a store of an age estimation system tended to discourage underage visitors from trying to buy age-restricted goods. And another finding was that the device gave confidence to store assistants, especially younger and less experienced ones, to ask customers for forms of identity that provided proof of age because it was less likely that a challenged customer would make a fuss if the assistant pointed to the device and said, “the computer says ‘no.’”

Although the device stores no facial images, it can gather and store analytical data concerning the demographics of a store’s customer base and the times of day that particular types of customers are most likely to visit, but, again, none of this data can be used to identify individuals. And another useful app that can be enabled allows the device to show adverts appropriate to the age and gender profile of a scanned customer.

Finally, there is one area where the MyCheckr could be used in respect of “age verification/facial recognition” but only temporarily and where people agree to their facial images being scanned for the purposes of, for instance, allowing them, customers or members of staff, to gain valid entrance to a frequently visited, restricted and gated area of a store without the need to prove their age each time. And this sort of system has been successfully stood on its head for “self-excluded” gamblers who want to ensure they are challenged when they attempt to use gaming machines.

We’re starting to see that this is a really exciting product for us.

Collecting Feedback

The MyCheckr device, which sells for about $500, is said to be easy to install and operate and uses about the same power as a low-powered laptop. It was released only a matter of months ago and so has not yet gone into commercial distribution, but it is in stores from where Innovative Technology is receiving feedback. Initial interest has been from smaller retailers, especially vape stores, but larger retailers are showing interest. “We’re starting to see that this is a really exciting product for us,” said O’Brien.

I have no expertise in either retailing or technology, but it seems to me that, if used extensively and diligently, this device could be an exciting product too for the vaping industry and THR at a time when child access to vaping products is at the top of the agenda. But how much difference could it make and how quickly? One obvious problem is likely to be that those retailers who are less fussy about challenging customers in respect of age—those causing most of the problem—are less likely than others to take up the technology. Why should they when they are doing alright the way things are? Why should they buy into this new technology when they don’t want the fuss of challenging their customers?

At this point, you realize that to encourage these retailers to change their ways, it is also necessary to have an adequately funded Trading Standards with the time and skills to challenge retailers who might be less than eager to be compliant. The government could consider making the use of such technology compulsory in all retail outlets where age-restricted products are on sale, but without the watchful eye of Trading Standards, there would be no guarantee that retailers would take any notice of the devices; they might not switch them on. The licensing of all retailers selling age-restricted goods might also help, but I’m certain this debate has been had by people far more in tune with these issues than I am.