Similar DNA Changes in Smokers and Vapers

- Featured News This Week Research

- March 20, 2024

- 0

- 5 minutes read

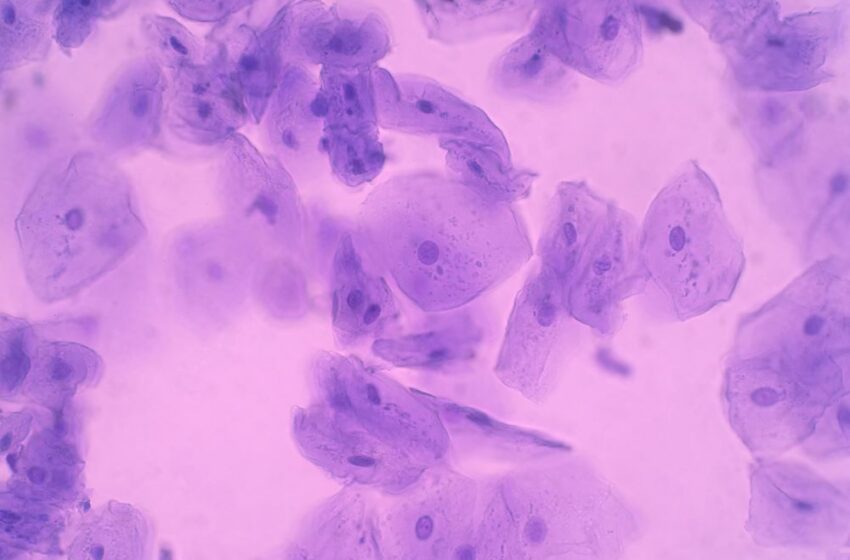

Image: tonaquatic

A new study from University College London (UCL) and the University of Innsbruck shows that e-cigarette users with limited smoking history have similar DNA changes to specific cheek cells as smokers, reports Medical Xpress.

The study was published in Cancer Research. It analyzed epigenetic effects of tobacco and e-cigarettes on DNA methylation in more than 3,500 samples to determine the impact on cells directly exposed to tobacco (e.g., cells in the mouth) and cells that are not directly exposed to tobacco (e.g., blood cells or cervical cells).

Data showed that epithelial cells in the mouth had substantial epigenomic changes in smokers. Similar epigenetic changes were seen in epithelial cells in the mouths of e-cigarette users who had smoked fewer than 100 tobacco cigarettes in their lifetime.

“This is the first study to investigate the impact of smoking and vaping on different kinds of cells—rather than just blood—and we’ve also strived to consider the longer term health implications of using e-cigarettes,” said Chiara Herzog, first author of the study.

“We cannot say that e-cigarettes cause cancer based on our study, but we do observe e-cigarette users exhibit some similar epigenetic changes in buccal cells as smokers, and these changes are associated with future lung cancer development in smokers,” Herzog said. “Further studies will be required to investigate whether these features could be used to individually predict cancer in smokers and e-cigarette users.”

“While the scientific consensus is that e-cigarettes are safer than smoking tobacco, we cannot assume they are completely safe to use, and it is important to explore their potential long-term risks and links to cancer,” said Herzog. “We hope this study may help form part of a wider discussion into e-cigarette usage—especially in people who have never previously smoked tobacco.”

The study also showed that some smoking-related epigenetic changes remained more stable than others after quitting smoking, including smoking-related epigenetic changes in cervical samples.

“The epigenome allows us, on one side, to look back,” said Martin Widschwendter, senior author of the study. “It tells us about how our body responded to a previous environmental exposure like smoking. Likewise, exploring the epigenome may also enable us to predict future health and disease. Changes that are observed in lung cancer tissue can also be measured in cheek cells from smokers who have not (yet) developed a cancer.

“Importantly, our research points to the fact that e-cigarette users exhibit the same changes, and these devices might not be as harmless as originally thought. Long-term studies of e-cigarettes are needed. We are grateful for the support the European Commission has provided to obtain these data.”

In response to the study, the U.K. Vaping Industry Association (UKVIA) released a statement.

“While the study data—which one leading academic has described as ‘crude’—implies a link to changes in cheek cells, which could potentially cause cancer, the study authors said their findings did not prove that e-cigarettes caused cancer,” the statement read.

“The study authors said their findings showed that vapes ‘might not be as harmless as originally thought,’ but it is important to make clear that nobody in the vape industry ever said that vaping was harmless. There are risks from vaping, but they are tiny compared to smoking,” the UKVIA said.

“This latest study,” the UKVIA statement said, “is also questioned by leading experts such as Peter Shields, an emeritus professor of medical oncology at Ohio State University. He states that critical pieces of information are missing and calls the smoking and vaping data that they are working from as ‘crude.’ He points to the fact that there is no biochemical verification that the vapers are actually not also smokers. He concludes that ‘researchers are still a far distance from being able to show causality, and the data looks like vapers are actually more like never smokers—implying their risk of cancer is not increasing by vaping.”