Pakistan’s dispute over cigarette exports to Sudan

By Stefanie Rossel

No matter the outcome, the situation is unlikely to yield any winners. In April, local news outlets reported that BAT subsidiary Pakistan Tobacco Co. (PTC) had asked Pakistan’s government for permission to fulfill a $20.5 million order from Sudan for cigarettes packed in boxes of 10 sticks each.

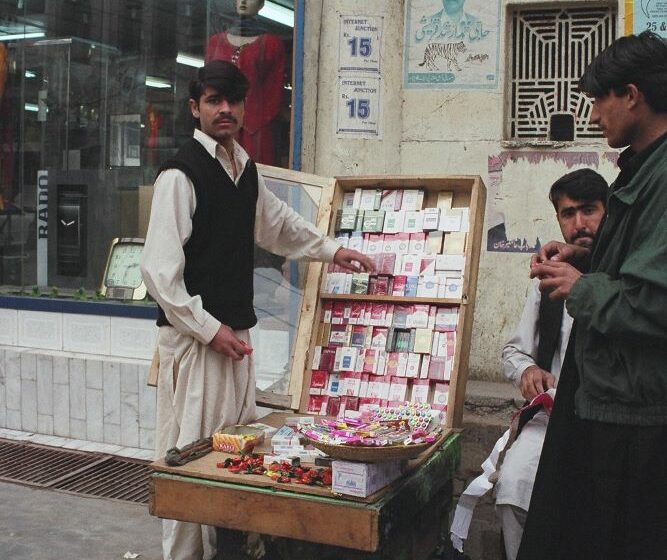

The sale would require a change of law. Under its Prohibition of Sale of Cigarettes to Minors rule, Pakistan bans the manufacture of packs containing fewer than 20 cigarettes. Health activists believe that small packs encourage smoking among lower-income groups, including minors, because such packs are less expensive than packs containing more cigarettes.

Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif approved PTC’s request on May 28 after a committee comprising members from various ministries argued that the 10-pack prohibition applied only to products intended for sale on the domestic market. The sale could proceed, the committee said, on the conditions that the manufacturer ensured product traceability, printed the text “For export purposes only” on each pack and agreed to submit quarterly export invoices to the health ministry.

The latter, however, has dragged its feet on giving the required green light. According to local press reports, the ministry has referred the matter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Meanwhile, PTC continues lobbying for a change of law.

The plans face strong opposition from health groups. Soon after learning about PTC’s plans, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids expressed concern, arguing that the move would not only jeopardize progress made in tobacco control but also directly target those most vulnerable to the harmful effects of tobacco consumption. The group’s country head for Pakistan argued that “kiddie packs” produced for export would inevitably find their way onto the local market, thus directly undermining efforts to discourage smoking among young people.

In July, representatives of 25 member countries of the African Tobacco Control Alliance wrote a letter urging Pakistan’s prime minister to prevent PTC from exporting small cigarette packs to Sudan. “If a product is too dangerous for one country’s children, it is too dangerous for children anywhere,” the signatories wrote. “Putting other people’s children at risk of tobacco addiction, disease and death is unacceptable—don’t put our African kids at risk by changing your strong tobacco control regulations in Pakistan.”

Due to the delay in obtaining permission, Sudan started contacting other countries to fulfill its order.

Both Pakistan and Sudan are parties to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which obliges them to prohibit the sale of cigarettes individually or in small packs. However, the treaty does not define what constitutes “small.” Of the more than 180 FCTC signatories, at least 82 member states require cigarettes to be sold in packs containing at least 20 sticks.

Weak Enforcement

The parties in the dispute now find themselves in a catch-22 situation. For Pakistan, it’s the decision between monetary gain and its tobacco control commitment. Battered by a severe economic crisis characterized by high levels of inflation, dwindling foreign reserves and a depreciating currency, the nation could certainly use the income.

PTC’s Sudan order, which the company says could be repeated, would bring valuable hard currency into the country. In March, the company was honored as one of Pakistan’s leading taxpayers. In 2023 alone, PTC paid more than PKR229 billion ($821 million) to the national exchequer in taxes and duties. According to Brecorder, the company has been exporting cigarettes to numerous foreign markets since 2019, earning the country $156 million. For the next fiscal year, PTC is targeting $60 million in exports. However, a third of that amount depends on the Sudan order.

“In the context of Pakistan’s economy, this export order is insignificant,” says Daud Malik from the Alternative Research Initiative, which conducts research in a variety of fields, including tobacco control, health, education, governance and culture, in Pakistan. “However, its consequences are adverse and extremely damaging to the tobacco control efforts in Pakistan. It would send all the wrong messages to everyone working to end smoking in Pakistan. It would raise questions about Pakistan’s commitment to FCTC and the commitment to a smoke-free country.”

Over the past decade, Pakistan considerably stepped up its tobacco control efforts, for which it was recognized by the WHO in 2021. In recent years, the country introduced a series of significant tax hikes on cigarettes. In February 2023, the government increased the federal excise duty on cigarettes by around 150 percent, resulting in a corresponding increase in cigarette prices.

However, the tax hike also boosted Pakistan’s already flourishing illegal cigarette market. An Ipsos study in May 2024 revealed a surge in smuggled cigarette brands. With consumers shifting from expensive duty-paid products to duty-avoiding products made at home or smuggled in from abroad, illicit share tobacco sales were expected to exceed half of Pakistan’s total market this year. Most locally manufactured tax-evaded brands, the study found, are available in packs of 25 and 30 cigarettes, encouraging single-stick sales among retailers.

For PTC, the loss of the Sudan order has other implications. If Pakistan does not allow exporting cigarettes in small packs, the company’s parent company may assign the order to affiliates in Bangladesh or Indonesia, a PTC official said. It would not be the first time that PTC lost export business because of Pakistan’s domestic regulations. In 2019, PTC lost an order for small packs from a customer in the Gulf region after the Ministry of Commerce gave permission but the health ministry did not.

While struggling to fulfill export orders, the manufacturer has also been coping with increasingly challenging business conditions at home. In May, BAT reportedly threatened to pull out of Pakistan if the government further increased cigarette taxes. According to the company, existing taxation had already caused its sales in Pakistan to plunge by 38 percent. “The past couple of years’ developments on fiscal policies have raised questions about the sustainability of the company’s operations in Pakistan,” Michael Dijanosic, regional director for Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa at BAT, was quoted saying in a meeting with the prime minister.

Growing Tobacco Market

Apart from the moral quandary implied by tobacco health activists about prevention of underage smoking in various continents, there is another ethical dilemma: Should a company export a product known for its adverse health effects to a country in the midst of a civil war?

“Demand for nicotine and tobacco products is bound to go up in war-torn regions and volatile markets as people try to deal with heightened stress, uncertainty and the destruction around them,” says Samrat Chowdhery, journalist and director of the Council for Harm Reduced Alternatives, an Indian registered nonprofit that works on tobacco harm reduction measures. “This was also evident during Covid as smoking rates went up in response to stress despite WHO warnings linking smoking to severe outcomes.”

With an anticipated cigarette market value of $1.9 billion in 2024 and a projected compound annual growth rate of 16.81 percent by 2029, according to Statista, Sudan is among the few countries still holding potential for tobacco companies. The local cigarette market is dominated by Haggar Cigarette and Tobacco Factory, a subsidiary of Japan Tobacco International, with a share of over 80 percent and BAT subsidiary Blue Nile Cigarette Co. The latter factory is based in Madani, which has been the scene of heavy fighting. The shift of production to Pakistan was meant to ensure the continuity of supply.

Tobacco taxes are a major source of income for the Sudanese government, with hefty taxes levied on both domestic and imported brands. Recently, nonduty-paid cigarette sales have been a significant issue, which could be acerbated by a shortage in legal supply.

“Denying people access to nicotine products in war regions in fact contributes more to their hardship than alleviates it, as smuggling takes over, hurting not just their meager resources as prices shoot up, like it is happening currently in Gaza,” says Chowdhery (see “In the Shadow of War,” Tobacco Reporter, October 2024). “But it also affects aid work as cigarette smuggling, due to higher profits to be made, gets prioritized over transporting aid supplies, which also in turn makes these shipments targets of attacks, hurting people in need of aid. In such an environment, ensuring safe, legal supply of nicotine or tobacco products is more humane and the lesser evil.”

Chowdhery recalls a recent foreign policy podcast describing how loyalties can be bought with cigarettes in Gaza. “So if BAT can ensure a legal, duty-paid supply of cigarettes to Sudan that does not violate the country’s local regulations while Pakistan, which is also struggling financially, can earn some revenue, I don’t see why it is being framed as a negative, especially when the alternative is smuggled cigarettes, which do not earn both countries any revenue, while increasing criminality and increasing stress, withdrawals and the economic hardships of smokers as well as people in need of humanitarian aid,” he says.