Dissecting Their Drives

- Also in TR Print Edition

- July 1, 2023

- 0

- 8 minutes read

Researchers, directors, analysts, public health experts and executives should realize that their lives may be very different from those of the consumer they’re studying. | Photo: Taco Tuinstra

To help nicotine users move down the risk continuum, it is crucial to understand consumer motivations.

By Jessica Zdinak

What drives change? And by change I don’t mean a short-term, temporary change but a long-term behavior change that alters entire lives. Most habits take around 14 days to “stick,” but behavior change that comes with an addiction works differently. This is what we face as scientists, public health experts, government officials, manufacturers and representatives in the nicotine and tobacco industry. Many of us want to save lives; some of us want to develop products for consumers to enjoy all while making a living and supporting our families. No matter what perspective we come from, I think we can all agree that taking a combustible cigarette smoker from cigarettes to an alternative, potentially reduced harm product often seems like a herculean task.

To some, it seems like an almost impossible task given the intricacies of product development, including the iterative process of prototypes, testing, retesting and validation of new products. This, combined with the extensive resources and time needed in the U.S. to get a new nicotine/tobacco product authorized by the Food and Drug Administration, leaves many people awake at night wondering if success is possible. I will argue that it takes many small steps by many people to drive success in today’s industry. And it starts with our consumer—the smoker.

It’s essential that we recognize every day how our lives as researchers, directors, analysts, public health experts and executives look nothing like the consumer we’re studying. Whether in the innovative and product development space, market research, regulatory research or FDA application submissions, if you don’t remember this, then you may find yourself wondering why you and your company aren’t as successful as you’d like.

At the Applied Research and Analysis Company (ARAC), before our team begins daily work activities, we go outside of our own lives, thoughts, feelings and behaviors and remind ourselves of the following:

We are not our consumers. We have biases and perspectives from a life likely not lived by our consumers. Get out of our heads and get into theirs.

It may benefit you and your company to learn one area of psychological science that helps you to understand what drives your consumers’ behavior and most importantly—how to change it. With science exponentially advancing over the years, it’s easy to forget and leave behind the most basic scientific principles of human behavior that got us to such an advancement. As a cognitive behavioral scientist, I see too many phenomenal researchers who look to the most recently published literature but fail to remember the science that this literature was built upon.

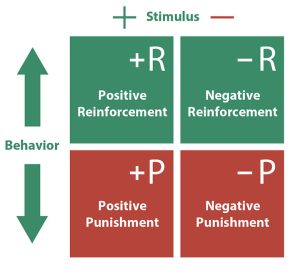

Some of the most basic scientific principles of behavior change revolve around a stimulus-response relationship, also known as operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). If you are a parent, you are likely to have heard some of this terminology before when referring to allowances for chore work, spanking for bad behavior, screen time for positive behavior, etc. Unfortunately, a lot of this terminology gets misused and is therefore misunderstood. Fortunately, however, the basic principles of this behavior change model are both still relevant and one of the most robust and successful ways to change behavior. We can think of this as a box with quadrants with two main variables:

The first variable is the actual behavior. Before applying this model, we have to ask ourselves, do we want the specific behavior in reference to increase or decrease in its occurrence. If we want to increase a desired behavior, we call this “reinforcement,” and if we want to decrease the undesired behavior, we call this “punishment.”

The second variable is the stimulus being applied to the individual, animal, etc. If we are applying a stimulus (giving something to the individual, animal, etc.), we call this “positive,” and if we are removing a stimulus (taking something away from the individual, animal, etc.), we call this “negative.”

When we combine these two variables, we get four outcomes that look like this:

- Positive reinforcement = applying a stimulus to increase a desired behavior

- Negative reinforcement = removing a stimulus to increase a desired behavior

- Positive punishment = applying a stimulus to decrease an undesired behavior

- Negative punishment = removing a stimulus to decrease an undesired behavior

Putting yourself into a smoker’s life, which of these four scenarios do you think would be most beneficial to changing their behavior? Does it seem appropriate to focus our efforts on the undesired behavior (smoking), or would it seem more helpful to focus efforts on a desired, more “positive” behavior, such as walking or exercising or the use of a potentially less harmful product? Some research has examined this (Borkowski and Leal, 2018), showing how policies and initiatives aimed at punishment (changing the undesired behavior through applying or removing a stimulus) may be ineffective and potentially misguided.

The catch here is that for this behavior change model to work, researchers and companies need to identify what the individual views as satisfying and pleasurable versus unsatisfying and uninteresting. It is likely that companies already apply some aspects of this in their regulatory, product and business strategies, but without a team of experts focused on this process, it is likely that they will come up short of their goals. It’s impossible to know what is satisfying versus unsatisfying to every single smoker in the world, but there are research methods, designs and analyses that are proven to identify and describe subpopulations, or “pockets,” of people (in experimental psychology, we call them “interaction effects”) that would all be in majority agreement of what is satisfying to them versus unsatisfying. Developing individual products to target each of these “pockets” of smokers would lead a company to be the first to have a consumer–focused portfolio of nicotine/tobacco products that encompasses the entire harm reduction continuum.

Of course, we know that there are other obstacles to be faced in this industry. We know that most of the public has incorrect perceptions of risk associated with products along the risk continuum. We know the challenges of having reliable access to all consumers, particularly those most vulnerable. Without federal government research experience, many people have questions on how to work with the regulator versus against them. Finding the right partnership within and outside your organization to help with these complexities is key to succeeding in this complex industry. Your consumer is a person with inward thoughts and feelings that drive their outward behavior—if you focus on understanding these aspects, you can’t go wrong. And who knows, you may develop that portfolio of products that puts an end to smoking!

Jessica Zdinak is the owner and chief research officer of Applied Research

and Analysis Co.