Out of the Bag

- Print Edition Smokeless

- September 1, 2020

- 0

- 0

- 11 minutes read

Regulators are trying to catch up with the rapid growth of nicotine pouches.

By Stefanie Rossel

It’s a niche within a niche, but it’s growing quickly. An analysis published by 360marketupdates values the global market for nicotine pouches at $619.9 million and projects it to reach $12.97 billion by 2026. This translates into a whopping compound annual growth rate of 53.8 percent.

The novel products have been rapidly adopted throughout Scandinavia and central and eastern Europe, according to Research and Markets. Nicotine pouches are the younger and “cleaner” siblings of Swedish snus, a pasteurized oral tobacco that has been around for some 200 years. Both products are discrete; consumers place them between their upper lip and gum where the nicotine and taste are then released. Snus and nicotine pouches are spit-free. After use, the pouch is disposed of in household trash.

Unlike snus, however, nicotine pouches don’t contain tobacco; they are white, pre-portioned bags composed of nicotine applied to a carrier material, such as food-grade fillers. They come in a variety of nicotine strengths and flavors, including mint, coffee and fruit. There are even nicotine-free variants. Like snus, nicotine pouches offer considerable potential for tobacco harm reduction because consumption does not involve combustion.

With 9 percent of men and 11 percent of women using cigarettes in 2018, Sweden has by far the lowest smoking rate in the European Union (EU). This enviable situation is widely attributed to the popularity of snus in that country. Decades of scientific research have confirmed the product’s efficiency as a smoking-cessation tool. A study published in the Harm Reduction Journal in November 2019 called snus “a compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes.” Using snus is estimated to be between 90 percent and 95 percent safer than smoking cigarettes, which puts the product on par with e-cigarettes on the continuum of risk scale.

Nevertheless, snus sales have been prohibited throughout the EU since 1992. (When Sweden became part of the EU in 1995, it negotiated an exemption from the ban.) Switzerland, a non-EU member, lifted its ban on snus last year. Following two unsuccessful legal challenges, the EU ban was again endorsed by the European Court of Justice in 2018.

In recent years, international tobacco companies have started including snus in their portfolios either by purchasing existing players or by developing their own products. And then they started developing the nicotine pouch. By now, all leading global tobacco firms are represented in the category, and nicotine pouches have been eating into the share of traditional snus. In the first quarter of 2020, nicotine pouches accounted for 6.7 percent of Sweden’s snus market, up from 3.2 percent in 2019, according to Swedish Match. In Norway, a non-EU member with a snus tradition, pouches today account for 25.8 percent of the snus market, up from 15.3 percent in 2018.

All present

Competition in the pouch segment has heated up significantly, and manufacturers are increasing production capacity for their “modern oral” products.

It all started with the introduction of Zyn by Swedish Match, the world’s largest producer of snus in Sweden and a significant player in the U.S. market for smokeless products. In the first quarter of 2020, Zyn was sold in 13 countries outside of the U.S. and Scandinavia, including many EU member states, such as Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, the U.K. and the Czech Republic.

Growth of Zyn has been so strong that Swedish Match CEO Lars Dahlgren spoke of a “transformational year” for the company, saying that the product had been the key driver of the company’s U.S. smoke-free sales in 2019. In the first quarter of 2020, Swedish Match sold almost 70 million cans of Zyn in the U.S., up from roughly 18 million cans in the same period a year earlier. Swedish Match also filed a premarket tobacco product application (PMTA) with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Demand for Zyn has been so strong that Swedish Match announced expansions of its U.S. production facility twice in short succession. Scheduled for completion in 2020, the fourth phase of expansion will increase capacity to more than 200 million cans per year.

Swedish Match’s competitors have not been idle. By acquiring an 80 percent stake in the global business of Burger Soehne, Altria in June 2019 became the owner of the On! nicotine pouch brand. Altria will provide global distribution for On!, which currently is available at retail outlets in the U.S., Canada, Sweden and Japan as well as globally through the company’s online shop. On! comes in seven flavors, including coffee, berry and citrus, and five different nicotine strengths. In May 2020, Altria submitted a PMTA for 35 On! products to the FDA.

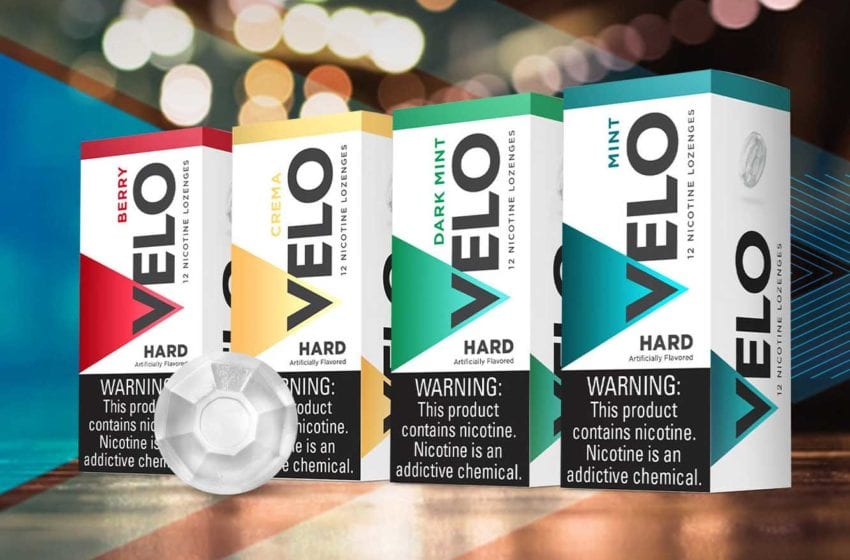

British American Tobacco (BAT) is represented in the nicotine pouch market through its Lyft brand, which it sells in the U.K., Sweden and Kenya. Going forward, BAT plans to market all its modern oral products under the name Velo—the brand under which BAT subsidiary Reynolds American Inc. (RAI) has been marketing its nicotine pouch product in the U.S. since June 2019.

To cater to the anticipated increase in demand, BAT in September 2020 built a nicotine pouch factory in Hungary. The investment, estimated at more than HUF7.5 billion ($24.3 million), the investment aims to boost production to more than 1 billion nicotine pouches in 2020, a figure that is expected to triple next year. Initially equipped with one line for the manufacture of nicotine pouches, the factory is supposed to receive a further five production lines by the end of this year. Its output is destined mainly for European markets, including Germany, Austria and the Nordic countries. The Hungarian factory is supposed to become one of BAT’s global hubs for the manufacturing of oral products.

In June last year, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) entered the race with Nordic Spirit, nicotine pouches that were developed in Sweden and sold in Switzerland and Sweden and online. Upon the launch, the company had said it intends to significantly increase distribution across various trade channels in the near term. Nordic Spirit is currently available in four flavors, including mint and bergamot wild berry.

Imperial Brands is present in the modern oral nicotine market with Zone X, Killa, BLCK and Pablo, among other products. With a high nicotine content of 50 mg per gram, Pablo is the “strongest” nicotine pouch in the market. Usually, nicotine content in the novel products vary between 2 mg and 24 mg per gram.

Product regulation

In the U.S., tobacco-free nicotine pouches are required to carry the warning “This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical,” and may be sold only to consumers over 21 years of age. Entry barriers are low compared to those for other tobacco products, but the product is subject to FDA regulation all the same. By contrast, the market for nicotine pouches in the EU currently operates in a regulatory vacuum. Containing no tobacco, the products are not covered by the EU Tobacco Product Directive (TPD2) nor do they belong to any other regulated product category. Unlike tobacco products, they may be advertised on television, radio and billboards throughout the common market.

Christofer Fjellner, who served as a member of the European Parliament from 2004 to 2019, expects new regulation to be adopted in all important markets in the coming years. In a report published in April 2020, he writes that Sweden and Norway will likely be the first countries to enact regulations for nicotine pouches—a development that could also influence how other European governments will shape legislation. For the time being, Sweden has decided that nicotine pouches are not a food product thereby indirectly approving the product to be placed on the market.

The country has started defining and categorizing nicotine pouches; its government has tasked a special commissioner with proposing new regulation. Meanwhile, Austria’s chemical authority is referring to the EU’s classification, labeling and packaging regulation, demanding that all nicotine-laced product carry health warning texts and symbols.

The World Health Organization has yet to take up the topic of nicotine pouches, according to Fjellner. He expects to receive an indication of how the European Commission views nicotine pouches in the implementation report for TPD3, scheduled for May 2021.

“How the EU chooses to regulate nicotine pouches is influenced by at least three factors,” he says. “Whether EU member states call on the EU to ban nicotine pouches, due to concern about the use of the product in member states—which was the reason for EU ban on snus—whether there are already specific product regulations or national bans in individual member states that new European legislation may be in conflict with, and the number of users of nicotine pouches, and thus a public opinion critical to a new restrictive legislation or ban.”

The latter, he adds, was one of the reasons e-cigarettes were not banned in the 2014 TPD revision. The way the EU regulated e-cigarettes in 2014, Fjellner says, could be an indicator of how it will likely deal with nicotine pouches, which would indicate a focus on warning texts and the introduction of a maximum nicotine level. For advocates of tobacco harm reduction, such an approach would be preferable over an outright ban.