A look at e-liquid bottling and packaging regulations

By Marissa Dean

Like anything in the nicotine industry, bottling and packaging are changing as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration introduces more regulations—PMTAs, testing requirements, labeling restrictions, etc. Being curious what regulations are in place for bottling and e-liquid packaging specifically, I turned to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) website and found this: “The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is the independent federal agency responsible for enforcing a key provision of the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 (CNPPA). … That law requires any nicotine provided in a liquid nicotine container sold, offered for sale, manufactured for sale, distributed in commerce or imported into the United States to be in ‘special packaging’ as defined by the Poison Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA). This packaging, in layman’s terms, must be designed to prevent children from accidentally accessing and ingesting liquid nicotine and must restrict the flow of liquid nicotine under specific conditions.”

Child-proofing e-liquid bottles makes sense. But are there other regulations? I hit a wall in my research here. Could bottles be made out of anything? Did labels and packaging have to have warnings on them? I went down the rabbit hole of bottling websites, anything from manufacturers to wholesalers. The most common theme between them was the conversation of glass bottles versus plastic bottles.

Glass is the obvious environmentally friendly option, but it has more potential for breakage and injury due to breakage. Plus there’s the added question of how to make them flow-restrictive to meet CPSC regulations. Plastic bottles are made out of different polyethylenes—polyethylene terephthalate, low-density polyethylene and high-density polyethylene. Plastic is not friendly to the environment, taking decades to break down, and even then, only breaking down into microplastics.

Recycling helps curb the problem, but many vapor companies lack fruitful recycling programs, if they have them at all. Bidi Vapor offers one for its Bidi Sticks, called Bidi Cares, but as far as bottles are concerned, it doesn’t seem like there are any specific programs outside of traditional city/county recycling programs.

Going further down the rabbit hole of packaging regulations, I found myself jumping from source to source throughout the vapor community, getting similar responses: “I’m not the right person to answer your questions, but try this person.” Eventually, I reached Azim Chowdhury of Keller and Heckman.

Chowdhury is a partner at Keller and Heckman, a law firm that specializes in regulatory law, including FDA, CPSC and packaging regulations in particular, and represents companies in the electronic nicotine-delivery system (ENDS) space. As such, he’s well versed in e-liquid packaging regulations. He told me that there are two federal agencies to look to: the CPSC and the FDA. Already having seen the CPSC regulations, I was curious what the FDA had to say.

Simply put, the FDA regulations for e-liquid packaging lie within the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA), the FDA Deeming Rule and premarket tobacco product application (PMTA) requirements.

The TCA “defines ‘tobacco product’ very broadly, in pertinent part, to include anything made or derived from tobacco intended for human consumption, including the components, parts and accessories of the product,” Chowdhury wrote in an email. The Deeming Rule extended the FDA’s tobacco authorities to cover e-cigarettes, e-liquids, pipe tobacco, hookah tobacco, cigars, novel and future tobacco products, among others. “Now, components and parts of newly deemed products are subject to FDA’s tobacco product authorities. With respect to e-liquid packaging, FDA has indicated that the ‘container closure system’ for e-liquids—the materials expected to come into contact with the e-liquid, such as the bottle, cap and dropper—would likely be considered a ‘component and part’ of the e-liquid, and, therefore, subject to regulation as a tobacco product because such materials are intended or reasonably expected to affect or alter the performance, composition, constituents or characteristics of the product.”

Accordingly, e-liquid manufacturers must provide detailed information with their PMTAs on the bottle/container closure system to demonstrate that the e-liquid, as packaged, is appropriate for the protection of public health, according to Chowdhury. “For example, in PMTA deficiency letters sent to e-liquid companies, FDA is requesting detailed information on the components of the container closure system (e.g., e-liquid bottle, cap, dropper). FDA has indicated that it is not sufficient to merely identify the components of the container closure system but wants applicants to completely characterize and specify the materials used in such components. In other words, FDA is requesting compositional details that will likely need to be obtained from the bottle supplier (and can be provided to FDA via confidential Tobacco Product Master Files).”

In 2019, the CPSC added the “flow restriction” requirement to its rule, stating that the 2015 law (child-resistant packaging) always intended to capture flow restriction. The CPSC “issued notices of violations to numerous e-liquid companies alleging that e-liquid bottles (specifically glass bottles) without flow restrictors rendered the e-liquid a ‘misbranded hazardous substance’ pursuant to section 2(p) of the Federal Hazardous Substances Act (FHSA),” according to the Keller and Heckman blog, The Continuum of Risk. “CPSC ordered these companies to initiate a number of ‘corrective actions,’ including to immediately stop sale and distribution, notify all known retailers and consumers and destroy and dispose of returned units and any remaining inventory.”

Because of the CPSC change, the agency issued hundreds of violation letters. Keller and Heckman sent a letter to the CPSC on behalf of a number of state and national vapor trade associations, pointing out that making the necessary bottling changes to meet CPSC requirements would run afoul of FDA’s prohibition on modifying currently marketed products without FDA authorization. The FDA, in the end, decided not to enforce PMTA change regulations for flow restriction modifications, encompassed in the “Compliance Policy for Limited Modifications to Certain Marketed Tobacco Products.” The guidance states that “this compliance policy provides that FDA does not intend to enforce violations of the premarket review requirements against such modified products [liquid nicotine products modified to comply with the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 flow restrictor requirements and battery-operated tobacco products modified to comply with UL 8139] on the basis of the modifications described in this guidance.”

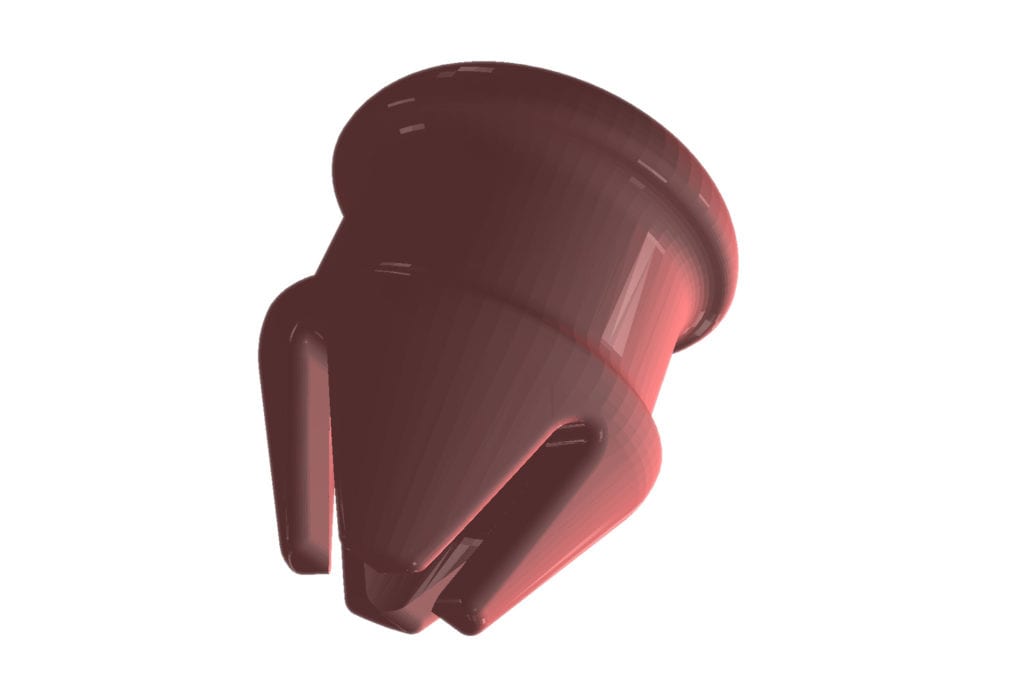

The industry tried to comply as best as possible; many premium e-liquid products that had previously been in glass bottles were switched to plastic bottles because there were no flow restriction capabilities in glass bottles. Glass bottles typically use droppers, whereas plastic bottles allow for squeezing. However, one innovative company in this space, Fluid Certify, has developed patent-pending technology to help address the glass bottle flow restriction issue.

Fluid Certify was founded by Cole McDonald, who also founded McDonald Vapor Co., an e-liquid manufacturer. In 2020, Cole passed away in a tragic climbing accident, and his mother, Lola McDonald, has kept the business going. Before Cole’s passing, he created flow restriction technology for glass bottles. Cole’s e-liquid products were packaged in unique glass bottles, and when the CPSC came out with its guidance, he conceived of his patent-pending technology to allow himself and others to maintain a level of excellence and offer alternatives to more generic plastic bottles.

The material used in Fluid Certify’s glass bottle flow restrictors is FDA food grade and offers flexibility and strength. It uses vacuum pressure and gravity to allow for repeated, uninterrupted use of a pipette. While the company is not currently mass producing the technology, it is not out of the question, according to Lola.

“Cole had a passion for the industry … he had no excuses for failure or blame—he found solutions,” Lola said of her son. His creativity and inclination for inventing opened the door to potentially “change things for the better” as he hoped to do. The company’s website, www.fluid-dynamic.com, offers more information on how to access the technology.

So what about the labels? While e-liquid labels are required to have basic information (name and place of business, amount of liquid contained, a nicotine addiction warning, etc.), the most critical FDA requirement is that they not appeal to youth. This is a broad requirement, and many companies received warning letters for products that mimicked kids’ foods, such as candy and juice. “My advice to clients is to keep their labels as simple as possible, keep it as mature as possible, and don’t use too many colors or graphics kids would enjoy,” said Chowdhury. The industry is “very subjective and competitive,” he added.

E-liquid packaging requirements are many, though it takes some digging to find them and guidance to navigate the nuance. With the growth and change in this industry, it will be interesting to see what comes next for e-liquid bottles and packaging.