Having added the Impex business to its portfolio, Airco DIET is busier than ever.

By George Gay

A once-popular saying had it that if you wanted to get something done, you were best off asking a busy person to do it. If this remains true, I would suggest that those with a project call the Airco DIET director, Keld Laigaard. In his own words, his company is at the moment: “busy—very busy.”

And this isn’t the sort of busy that occurs when things head south and everybody has to run around looking for business. Despite the fact that many countries are still clawing their way out of recession, and perhaps in part because of this situation, Airco DIET has had to take on new staff as it works on existing contracts, deals with an ever-increasing level of interest and assimilates the Impex business acquired from IPEL Ltd. toward the end of last year.

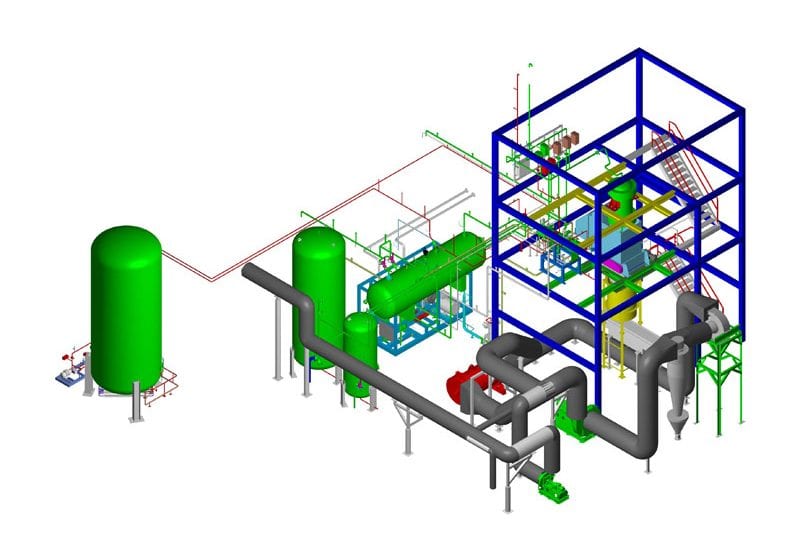

The future, too, looks good, especially if, as some people expect, leaf tobacco supplies become restricted and there are further, stricter regulations on the contents and deliveries of tobacco products. For those unfamiliar with the process, DIET (dry ice expanded tobacco) high-expansion technology uses CO2 to puff up the intact cells of cut tobacco and then removes the CO2 in such a way that the expansion—in the range of 110-140 percent—is maintained. Tobacco savings are not the only advantage, however, because whereas regular tobacco is variable, DIET tobacco offers a stable filling capacity with a taste that is unchanged, though reduced in intensity. It provides the manufacturer with a tool to reduce and control delivery levels, mainly tar and nicotine. And it adds a degree of stiffness to the tobacco, which has the advantage of improving the draw of cigarettes.

When I spoke with Laigaard in the middle of last year, he told me that the level of inquiries for DIET plants was the highest it had been in 25 years. Last month he told me that nothing had changed, though whereas previously just about all of the interest had been focused on Airco DIET’s smallest, 300 kg/hr, plant, now there was interest also in the next size up, the 600 kg/hr plant.

“We are still seeing an increase in interest,” he said. “We’re building a tolling [contract DIET] facility just outside Jakarta. That is a little bit more than a DIET plant, and it’s taking a lot of manpower. But it’s a good big project for us. So with that and with some nice orders we got late last year, we’re busy—very busy.”

By the time it is completed at the end of this year, the Jakarta plant will provide a facility where manufacturers will be able to deliver their tobacco, have it expanded and then shipped back to them. It is being built, according to Laigaard, to facilitate the huge demand for DIET tobacco that is coming from smaller companies that don’t have the funds or the usage levels that would pay for or warrant their own DIET plant. So the Jakarta facility will give them the opportunity to have their own tobacco expanded or to buy expanded tobacco for use in their own blends.

Unexpected inquiries

Meanwhile, interest in expanded tobacco is coming from some new directions, and even Laigaard had to admit that he had been caught somewhat off guard. “I had always thought that DIET was for cut rag,” he said. “But we have been contacted several times, not only because of Impex, but because of DIET, for processing roll-your-own tobacco, which, while it is similar to cut rag, is actually a little bit different.

“And the cigar industry is talking to us about reducing the amount of filler being put into a cigar and about producing a lighter product in line with demand from younger people. Cigar filler is not like cut rag; it’s more like broken-up leaves. But you can actually put it through a DIET plant and it comes out very nicely, which is something I didn’t know. So I have learned something new. I know it’s being done. I have the product with me. It looks very good.”

One of the interesting aspects of this development is that, as is mentioned above, Airco DIET recently acquired the rights to the Impex process and that process has been associated with cigar filler expansion. So I asked Laigaard whether or not the discovery that the DIET process could also be used to process cigar filler was a complicating factor.

Not really, he replied. Most manufacturers who made enquiries largely had their minds set on what they wanted. Some wanted to go the DIET route and some wanted to go the Impex route.

While both systems provide high levels of expansion, the Impex process uses isopentane rather than carbon dioxide as the expansion agent. Isopentane does not dissolve nicotine and other volatiles, so the expanded product maintains its original flavor and color.

Of course, the Impex process is very much the junior partner to DIET in the Airco DIET portfolio, so I asked Laigaard what advantages would accrue from the acquisition.

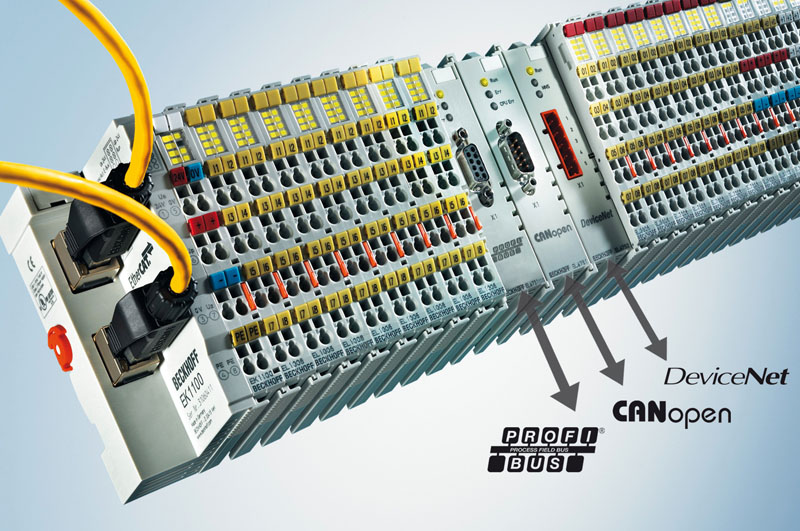

“Well, I think we will be able to serve the customer with a wider portfolio of high-expansion products,” he said. “While the DIET process has a distinct way of treating the tobacco, Impex has a different way of doing it, one where you can do a whole blend that is already flavored. You can expand that and go straight to roll-your-own pouches or direct into the cigarette maker. So it is a different process that gives different opportunities. We can go out and we can give the customer a little bit more to choose from.”

Mutually beneficial

In fact, the relationship between Airco DIET and its Impex customers is going to be a closely symbiotic one for some time to come. Airco DIET has assisted the tobacco industry by taking on board the Impex process, which otherwise might have disappeared from the scene. It has acquired all of the documentation associated with it and it can now carry out servicing, maintenance and the supply of spares. In fact, Laigaard says that it has everything it needs to assist existing customers.

And, of course, Airco DIET has the skills to enhance the system, though this, apparently, is hardly necessary. Laigaard told me that the Impex system was a very good one, though Airco DIET would be putting some effort into refining installation procedures. Installation times in the past had been overly long and had not always run to schedule, Laigaard said, and this was not something that Airco DIET could live with. “We have to, and we are, working on getting the package complete, so that when we go out and sell a system, we can give a timeline to the customer, one that will run on schedule and on budget,” he said.

So this is what Airco DIET can do for Impex customers, but those same customers have something to offer Airco DIET too, because many of them have considerable experience in running these plants, which are still fairly new as far as Airco DIET is concerned. “We have a very good relationship already with these people,” Laigaard said. “And we feel that they are going to help us in areas where we are not so strong because this is a new process for us. Obviously, we don’t know all of the details yet.”

With this in mind, Airco DIET has been busy making contact with as many Impex customers as it can and has already established relationships with Impex plant owners in Europe and the U.S. that are willing to carry out test runs on the tobacco of potential customers.

Finally, I asked Laigaard whether this sort of relationship was important to him. Yes, he said. Obviously, Airco DIET was interested in selling more systems and products, but the industry was getting smaller and smaller, and the more people who actually liked you the better off you were. Airco wanted to have a good name and reputation because, in the end, your reputation was all you had to run with.

<sidebar>

Reconstituted tobacco with cactus

Expanding tobacco either through the DIET or Impex process is a very effective way in which tobacco manufacturers can help reduce their usage of leaf tobacco, their most expensive ingredient, while at the same time helping to stabilize their products.

Another way to achieve these sorts of benefits is through the use of reconstituted tobacco, which allows manufacturers to use tobacco that might otherwise be wasted.

Of course, reconstitution would offer even more of an advantage if the sheet produced contained, as well as tobacco, something that was not as expensive as tobacco … cactus perhaps. And currently, China Kangtai Cactus Biotech (Kangtai), in conjunction with Shandong Yishui Ruibosi Tobacco and the Qingdao Cigarette Factory, is manufacturing just such a product—reconstituted tobacco sheet with cactus.

Kangtai is a leading grower of cactus plants as well as a developer, producer and marketer of cactus-derived products, including nutraceuticals; nutritious food; health and energy drinks; beer, wine and liquor; extracts and powders; and animal feed. Its high-quality “green” products are sold throughout China through a distribution network that covers 12 of China’s 23 provinces and two of the country’s four municipalities. And as part of its extensive research, it has developed a method for producing reconstituted tobacco that also contains cactus, a product that offers several advantages.

For instance, its cigarette brand, Sheng Cao, which is made in its own plant in Macao, has in the past been blended with tobacco, cactus, honeysuckle, ginkgo and tea leaves, a mix that is said to produce a very special flavor. But the company has found that the addition of reconstituted tobacco sheet blended with cactus further improves the taste of the cigarette while helping to control delivery levels.

Kangtai does not produce the reconstituted sheet itself but has signed an agreement with Shandong Yishui Ruibosi Tobacco (Ruibosi), a subsidiary of China Tobacco Shandong Industrial, which apparently is one of the four tobacco manufacturers in China designated by the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration to develop reconstituted tobacco using paper process technology.

Kangtai’s CEO, Jinjiang Wang, said earlier this year that samples of the new reconstituted sheet had been produced and that full production was planned to begin in May. And Ruibosi seems to be keen to take the project forward. Vice president Changsen Xue said Kangtai was an outstanding company that had shown remarkable growth in the cactus business. “We have great confidence in the future sales of Sheng Cao cigarettes, which we believe will have very promising market prospects and growth potential,” he said. “We have no doubt that consumers will like the taste very much.”

Meanwhile, Kangtai has signed, also, a joint manufacturing agreement with China Tobacco Import and Export Shandong Corp. (China Tobacco Shandong) to manufacture Tai Shan Sheng Chao cactus cigarettes.

The company is manufacturing this new brand, also using reconstituted sheet, in conjunction with China Tobacco Shandong’s subsidiary, the Qingdao Cigarette Factory. Full production was due to begin in February this year.

And whereas Sheng Cao cigarettes are sold in China, there are plans to sell Tai Shan Sheng Chao through China Tobacco Shandong’s established sales channels also in Russia, South Korea and Japan.

“This agreement creates mutual benefit for both companies,” said China Tobacco Shandong’s general manager, Jianli Bi. “The low-nicotine and non-nicotine cactus cigarette product coincides with the government’s initial step to promote less harmful products to the huge smoking population in China ….”

Kangtai does not make any health claims for its cactus cigarettes, however. I asked Frank Hawkins of Hawk Associates, a Florida-based investor relations firm that is working with Kangtai, whether any studies had been carried out into whether cactus cigarettes did offer a health benefit, and he said that Kangtai only made the point that because the cactus substituted for tobacco, the delivery levels of cigarettes containing cactus would be lower than would otherwise be the case.

Nevertheless, Hawkins is enthusiastic about the new products, partly because, as he points out, people living in the West aren’t exposed to too many cactus products. “But Kangtai is into that sort of thing,” he told me. “They have a big nutraceuticals business, they have a big beverage business and they sell the raw materials to others.

“Then, about a year or so ago, they came up with this whole idea of doing a cigarette. And it’s gotten everybody excited. They have sent samples to us and we have passed them around to investors, and they have created some excitement among investors. And now they think they can create a bit of an export business.”