Meanwhile, just over a year ago, the FDA issued a press note on reducing the addictiveness of cigarettes in which the agency’s commissioner was quoted as saying that nicotine was “powerfully addictive” and that “[m]aking cigarettes and other combusted tobacco products minimally addictive or nonaddictive would help save lives.”

The next paragraph had it that “[a] paper published by the FDA in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018 projected that by year 2100, a potential nicotine product standard could result in more than 33 million people not becoming regular smokers, a smoking rate of only 1.4 percent and more than 8 million fewer people dying from tobacco-related illnesses.”

Sounds impressive? Perhaps, though “… potential nicotine product standard could …” sounds less than convincing to me, and the above should have read, I hope, “… 33 million people, who otherwise would have, not becoming regular smokers ….” But the important question you need to ask is would the number of smoking-related premature deaths fall in the period up to 2100? Let me explain.

The second paragraph of the press note opens with the statement that has become almost de rigueur in the case of FDA communications: “Each year, 480,000 people die prematurely from a smoking-attributed disease ….” Now, 480,000, that is the same number of people who were said to have died prematurely from smoking-attributed diseases annually between 2005 and 2009.

In 2009, the year the TCA was signed into law, the U.S. population was about 306 million, and the adult smoking rate was about 21 percent, meaning there were about 64 million smokers in the country. Currently, the population is about 334 million, and the smoking rate is about 12 percent, meaning there are about 40 million smokers. What this seems to mean is that the FDA has managed to hold the annual premature death toll from smoking-attributed diseases at 480,000 during a period when the number of smokers has fallen by more than 37 percent. That gives a whole new meaning to the word “control” in the Tobacco Control Act.

Even if these figures are not quite as they seem to be, the question must be asked whether the FDA is on the right track. I think there are a number of reasons to suggest that it is not, but the most important is that the agency seems to favor the speculative over the obvious. For instance, if you follow one of the links from the press note, you will come to a passage titled “Where do e-cigarettes fall on the continuum of risk,” which includes a statement saying, “many studies suggest e-cigarettes and noncombustible tobacco products may be less harmful than combustible cigarettes,” a statement qualified by “[t]hough more research on both individual and population health effects is needed.”

This is obfuscation—a two-way bet. You’ll notice the statement doesn’t spell out why this extra research is needed. And, typically, it gives no indication of how long is needed for such research. Of course scientists say more research is needed. I believe more stories are needed.

E-cigarettes and noncombustibles clearly provide a fast-track route for many people out of smoking, and relatively harmless recreational drugs for nonsmokers, but the FDA seems intent on holding up the development of such products and their launch onto the market and even seeks to remove them from the market, especially if they even whisper the word menthol.

Contrast this obstructive attitude to e-cigarettes with the FDA’s promotion of low-nicotine cigarettes, the consumption of which will keep smokers inhaling tar, which the agency sees as the dangerous component of tobacco smoke. Such promotion has been allowed even though the “science” of low-nicotine cigarettes and addiction seems little understood by the FDA. The press note was titled “FDA Announces Plans for Proposed Rule to Reduce Addictiveness of Cigarettes and Other Combusted Tobacco Products.” Plans for proposed rule? That is one mighty qualification. It brings to mind the strapline to the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?: “They had a plan but not a clue.”

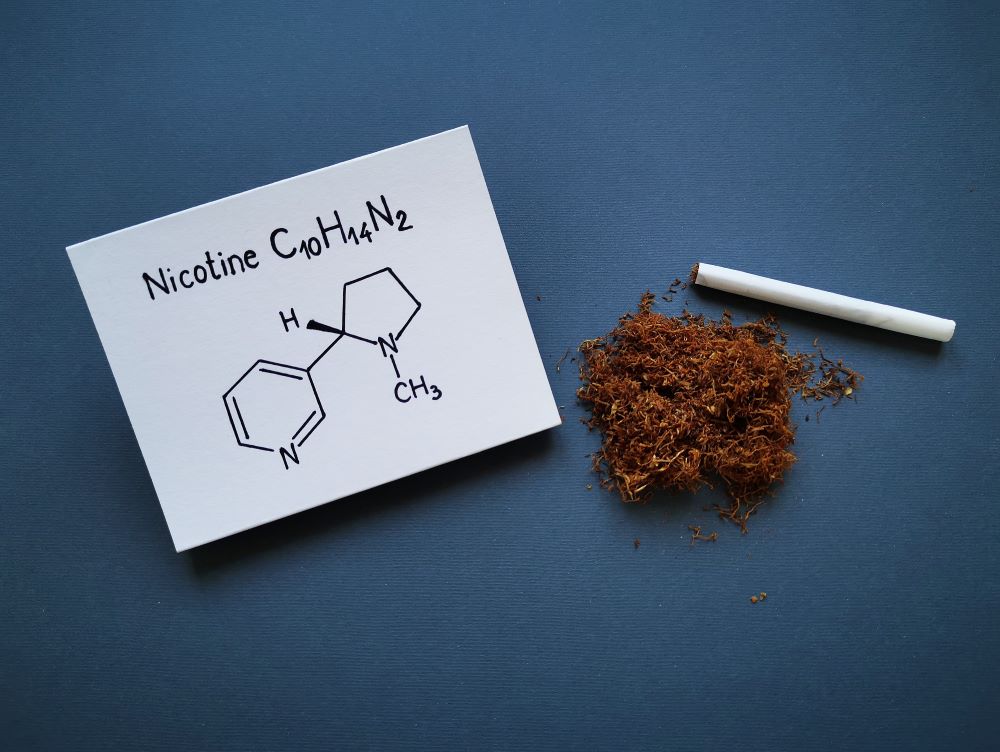

The heading uses the term “addictiveness,” implying there are levels of addictiveness, an idea I have always found odd. Surely, addiction implies a compulsion to do or consume something that causes harm, and there can be no degrees of compulsion. Smoking might be considered addictive, but vaping cannot because vaping does good, not harm, in allowing a smoker to quit. But the press note speaks of nicotine as being powerfully addictive even though the FDA concedes elsewhere that nicotine is not harmful while at the same time saying tobacco products are potentially minimally addictive even though the agency believes the tar from cigarettes is harmful.

To me, the language used and the thinking behind the low-nicotine project are all over the place, and this seems to indicate that the FDA does not truly consider how its words will be received and how its plans will play out in the real world.