The effort to correct nicotine risk misperceptions will be a marathon rather than a sprint.

By Stefanie Rossel

“Nicotine contained in tobacco is highly addictive, and tobacco use is a major risk factor for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, over 20 different types or subtypes of cancer and many other debilitating health conditions.” With phrases like this, the World Health Organization links the undisputed harms of burning and inhaling plant tissue with the ingredient smokers seek in a cigarette.

Regardless of its form of delivery, such statements suggest, nicotine is the devil incarnate. In spreading this message, it appears, the WHO has done a good job. In a 2021 study funded by the National Cancer Institute, 83.2 percent of surveyed U.S. physicians “strongly agreed” that nicotine directly contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease. Nearly 81 percent thought it contributes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and 80.5 percent associated nicotine with cancer.

While recognizing that nicotine is responsible for the addictive nature of tobacco products, the study authors pointed out that the strongest evidence for direct causality for nicotine is for birth defects (neurodevelopment), with only limited evidence supporting causal links to cancer and cardiovascular disease and scarce data for COPD. The misperception that nicotine is responsible for smoking-related health risks, they observed, is not only common among the public but also among other healthcare professionals.

“Correcting misperceptions should be a priority given that in 2017, the FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] proposed a nicotine-centered framework that includes reducing nicotine content in cigarettes to nonaddictive levels while encouraging safer forms of nicotine use for either harm reduction (e.g., smokeless tobacco) or cessation (pharmacologic NRT [nicotine-replacement therapy]),” the study concluded.

In product use, risk perceptions play a critical role; they can influence smokers’ decisions on whether to switch to products with lower risk profiles. The messaging is an essential part of changing misperceptions. Studies on nicotine corrective messaging have shown that it was effective in decreasing misperceptions of nicotine harm, but repeated exposure to such messaging was necessary to reduce false beliefs about nicotine and tobacco products.

With physicians and other healthcare professionals often being the first point of call for people seeking to quit smoking, it is obvious that their misperceptions should be corrected first so that they can educate their patients and accurately convey nicotine’s relative and absolute risks.

Carolyn Beaumont, a general practitioner (GP) from Victoria, Australia, has taken on the challenging task of educating her colleagues. Since July 1, 2024, all nicotine vapes in Australia have been regulated as therapeutic goods, which means they are available only at pharmacies to help people quit smoking or manage nicotine dependence. Currently, all buyers of nicotine vapes require a prescription from a doctor or a nurse practitioner.

Starting Oct. 1, the rules will be somewhat relaxed. From that date, people 18 years or over will be able to purchase therapeutic vapes directly from a pharmacy without a prescription. People under 18 will still need a prescription to access vapes, where state and territory laws allow it, to ensure they get appropriate medical advice and supervision.

The concentration of nicotine in vapes sold in pharmacies without a prescription will be limited to 20 mg per milliliter; people who require vapes with a higher concentration of nicotine will still require a prescription.

The law requires pharmacists to consult customers of both prescription and nonprescription vapes before allowing them to make a purchase.

Following the announcement of the new rules, several major pharmacy chains in Australia stated that they will no longer stock vapes. Beaumont is not surprised: “They simply don’t have the time, product knowledge or resources to advise customers on appropriate products and use. It is greatly complicated because any pharmacist-only product must be an approved medical product, yet there are no approved vapes in Australia. They are listed but not approved. Fortunately, there are some online pharmacies who specialize in vapes, and these will continue to operate but likely will require a script to avoid the ‘nonapproved’ issue.”

“There is no official doctor education in Australia that adequately presents the fuller context of smoking, vaping and nicotine.”

Enjoyment Doesn’t Feature

Despite the hostile environment for nicotine, Beaumont says she has found that her colleagues are quite interested in the field of tobacco harm reduction (THR). “Yet, to communicate THR on a larger scale, typically via continuing medical education (CME) courses or webinars, is difficult. These generally require support from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), and to date, there is no official doctor education in Australia that adequately presents the fuller context of smoking, vaping and nicotine,” she says.

“In medical school and as a trainee GP, we were taught of the many smoking-related health and social issues. But a more nuanced understanding of working with smokers wasn’t appreciated. We all knew the ‘three A’s’ approach—ask, advise, assist—the measure of nicotine dependence—time to first cigarette—and the first line NRTs. Yet it stopped there as though magically, smokers would be motivated to quit, and this would happen within six months. If not, repeat the process ad nauseum.”

According to Beaumont, doctors aren’t taught that some smokers like nicotine and simply want a less harmful alternative. “Enjoyment doesn’t feature in medical education,” she says. “Doctor support can truly help some people reduce their use. But it’s not enough for many heavy smokers, and they often become disengaged with the same messaging they keep hearing from doctors.”

Beaumont is encouraged, though, that Australia’s GP College recently revised its smoking cessation guidelines and increased the recommendation of vaping from “low” to “moderate.” “I hope this will have a reasonable impact on doctors’ willingness to prescribe, or at least be open to the conversation,” she says. “I also hope this signals a greater willingness by the RACGP to support vape-related CME that is broader in scope and includes input from ‘progressives’ such as myself.”

Beaumont first became aware of vaping as a cessation tool in 2020 when Australia was on the verge of making vapes prescription-only. “My approach was simply this: I listened to the needs of smokers and vapers,” she says. “It didn’t take long before I was convinced of [the] merits [of vaping], and also, I developed a deeper understanding of nicotine use and addiction. Compassion and health improvements were, and still are, the underlying reasons why I’ve remained involved in this field.”

Beaumont aims to help disadvantaged groups, which are among the most affected by smoking-related death and disease. “It is simply unjust that smokers are also affected by nicotine myths, and it is getting to the point where people think that smoking is better than vaping.”

“Like so many areas where science is contested, adherents of contrarian positions are rarely persuaded by more science or data.”

Open Dialogue Required

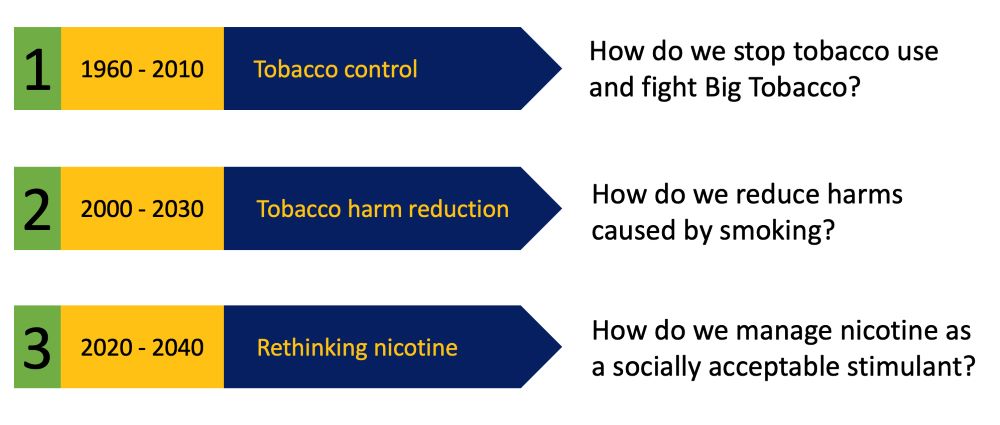

While some believe that science will correct misperceptions of nicotine, others are skeptical, pointing, for example, to the WHO’s proposal to define aerosols as smoke. Derek Yach, a global health expert originally from South Africa who played a key role in crafting the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, says that while some topics require more research, these gaps should not delay WHO support for THR, noting that they have not prevented the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other government agencies from authorizing a range of reduced-risk products.

“Like so many areas where science is contested, including vaccine benefits, climate change or even beliefs that the earth is flat, adherents of contrarian positions are rarely persuaded by more science or data,” says Yach. “Their views deeply reflect emotional, ideological and sometimes cultural views based on their life experiences. A mother whose child gets autism after a vaccine is easily convinced that vaccines are dangerous. A tobacco control advocate who experienced tobacco industry subversion of public policies keeps that view and doubts anything new coming from industry.”

Having worked on all sides of the issue and having spoken with a wide variety of stakeholders, Yach says that there is no shortcut to finding safe spaces to not only talk honestly about the science but also examine the reasons behind the mutual suspicion. “I saw this bear fruit in the declining years of apartheid when talks about talks led to a peaceful transition of power,” says Yach. “It is possible in that setting; it must be possible in our world.”

The Morven Dialogues, a series of meetings between U.S. public health officials and tobacco industry representatives first held in 2012, have been a modest example of what is needed, according to Yach.

“They recently reported on their March 2024 meeting, which brought together industry with some public health leaders in the U.S.,” says Yach. “Further, I see signs of hope in a recent article by authors from public health I have long respected. They argue for dialogue between scientists in the public sector and industry—as I have—and not for boycotts and bans.”

Without agreement on the basic scientific issues and progress on correcting disinformation, sound policies are unlikely. “A study of how change happens in public health shows that it always starts with physician acceptance of the evidence,” says Yach. “They apply that evidence to themselves, to their patients and through organized efforts to public policy. Recall that no country has ever seen a reduction in their smoking rate before it goes down in physicians. I suspect that is true regarding uptake of THR products. And that starts with doing more to have disagreeing groups talk.”

It’s going to be an uphill struggle, though: In mid-June, the WHO in a press release expressed “grave concern over the tobacco industry’s manipulative tactics aimed at influencing healthcare providers through continuing medical education programs and thereby advancing the interests of the tobacco industry.”