Will the European Union enable or obstruct the market-based demise of the cigarette?

By Clive Bates

There are so many genuinely terrible ways to regulate combustible tobacco and smoke-free nicotine products that achieving one of the less terrible ways is a triumph. Unlike the United States, the European Union hasn’t imposed gigantic regulatory burdens that choke the life out of all but the largest companies, relentlessly favoring tobacco majors over their smaller rivals. Unlike Australia, the EU pulled back from regulating vapes as if they were medicines. Australia was once a leader in tobacco control, but now it has become a chaotic fiasco of sluggish declines in smoking and a massive black market. Despite the prohibition campaigns of the World Health Organization, the EU has resisted most forms of prohibition, though with the inexplicable exception of snus. To state the obvious, prohibition doesn’t cause banned products to disappear; it merely removes law-abiding suppliers and hands the residual market to criminals and unregulated informal traders.

In contrast, the EU has developed a range of measures to address tobacco and nicotine risks that are not especially disproportionate or discriminatory, reasonably precautionary and not particularly prone to harmful unintended consequences. As a result, the EU has a diverse range of lawfully available safer alternatives to smoking and, therefore, the regulatory basis for tobacco harm reduction for the member states that wish to pursue it. By international standards, it is a modest success.

European elections will be held in June 2024, and a new legislative program will emerge a few months later, with the most intensive legislative activity expected in 2025. So, the question is where next? I am sorry to report that the Brussels hive mind of bureaucrats, politicians and interest groups is on course to turn a modest success into a conspicuous failure, putting millions of lives at risk.

The EU’s Public Health Aims are Focused on Reducing Disease

There is a renewed impetus behind EU tobacco policy. In 2021, the EU launched its plan for addressing cancer, Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. In 2022, it launched a separate plan for addressing noncommunicable diseases other than cancer, known as Healthier Together. Both place considerable emphasis on tobacco, and both stress the “tobacco-free generation” objective to reduce tobacco use to less than 5 percent of adults by 2040 compared to around 25 percent today.

Regulatory Instruments

To deliver this agenda, the EU has three main instruments to regulate tobacco and related products, such as e-cigarettes. These are in the form of “directives,” or legally binding agreements that member states will implement in domestic legislation that complies with the terms of the directive.

- The Tobacco Products Directive (TPD: 2014/40/EU) governs standards for products, packaging, warnings and several aspects of commerce in tobacco products. This directive also provides for the regulation of e-cigarettes, including advertising and promotion of these safer alternatives. The TPD is under active review following an evaluation of the legislative framework for tobacco control, and a new European Commission (EC) proposal is expected late in 2024.

- The Tobacco Advertising Directive (TAD: 2003/33/EC) bans tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship with a potential cross-border reach. Member states control fixed advertising, such as billboards. The TAD will likely be revised alongside the TPD to create a unified approach to tobacco and related products, such as e-cigarettes.

- The Tobacco Excise Directive (TED: 2011/64/EU) provides a framework for harmonizing tobacco tax design. Member states generally set the levels of excise duty but are subject to minimum levels set in the directive. The TED has been subject to a lengthy review process since 2016. Taxation matters are sensitive with the member states, and each has a veto on any proposals. Controversy struck on Dec. 7, 2022, when new proposals were pulled from publication, as several Eastern European nations noticed that it would create large increases in tobacco prices for them.

The EU, as a party to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, will also form a common position to take into the November negotiations at the 10th Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Panama. By endorsing the positions of the WHO, the EU will build momentum for further regulation aligned with the WHO approach.

The EU also has a range of softer instruments, such as the nonbinding 2009 Council Recommendation on Smoke-Free Environments (2009/C 296/02). In July 2022, the EC issued a call for evidence for a proposal for an updated recommendation that would apply to heated-tobacco products and e-cigarettes.

The Outlook is Bleak

It is never easy to see the big picture in the EU through the relentless blizzard of initiatives, consultations, reports, working groups and statements. However, some disturbing developments are emerging.

First, the major error of strategy. The EC sees the newer tobacco and nicotine products (heated tobacco, pouches, e-cigarettes) as a threat rather than as an opportunity to reduce cancer and NCDs. There is no sign that it recognizes or is interested in exploiting the radically different risks to health posed by smoked and smoke-free products. It should be treating tobacco products differently and proportionately according to risk. However, it is moving in the opposite direction toward treating all tobacco and nicotine products as if they were cigarettes. The effect will be to protect the cigarette trade, promote smoking, slow the decline of serious diseases and nurture the criminalization of supply and workarounds.

Second, instead of reversing the absurd and indefensible ban on snus, rumors suggest that the EC may even try to extend this ban to nicotine pouches. Snus has already reduced adult smoking in Sweden to close to the EU’s 2040 tobacco-free target of 5 percent, with measurable improvements in cancer and cardiovascular outcomes. Encouraging “free movement” of pouches would build on the snus proof-of-concept and help to reduce smoking across the EU. Regulation of purity and total nicotine density in pouches makes sense. However, a ban will simply deny users a significant harm reduction opportunity and create an influx of illicit high-strength pouches.

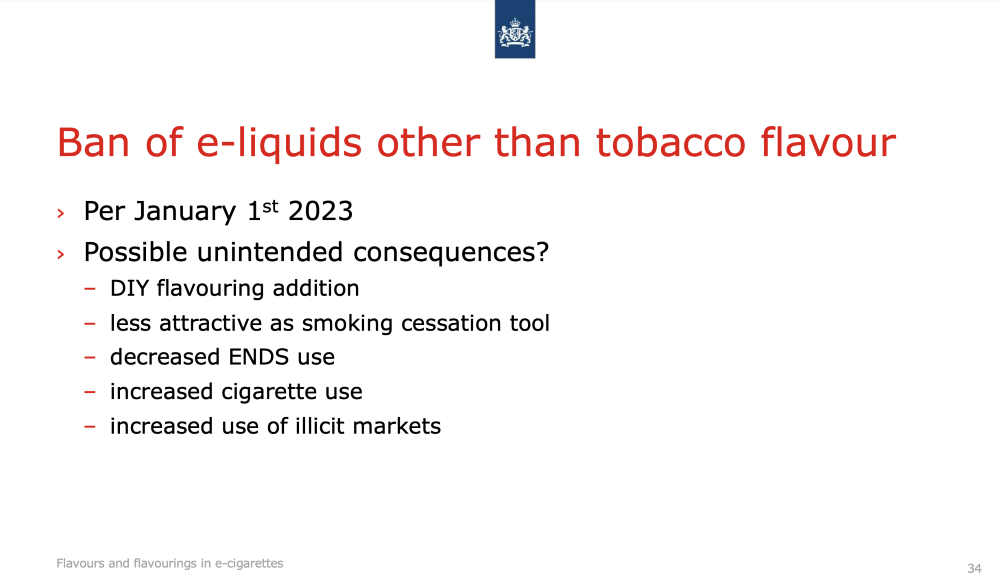

Third, there are moves to extend the ban on characterizing flavors in combustible tobacco products to all nicotine products. The EC has already done this for heated-tobacco products and could extend severe ingredient restrictions to vaping products. The government of the Netherlands, in alliance with the public health agency RIVM, has adopted a “whitelist” approach of permitting a few ingredients used chiefly to make artificial tobacco flavors. If adopted by the EU, this system would radically constrain the legal vaping market in which consumers are drawn to the diversity and ever-changing range of flavors as an alternative to smoking. At a December 2022 conference presentation in Paris, an RIVM official, Reinskje Talhout, presented on the Netherlands’ approach. After 33 pages of detailed analysis showing how to create a (short) list of permitted ingredients, she included the following slide on “Possible unintended consequences.”

The challenge is well summarized on this slide. Yet the advocates of broad flavor bans have no response. They have largely ignored the malign market and behavioral dynamics that they are likely to unleash.

Fourth, changes in the excise regime will dull the consumer economic incentives to switch from high-risk cigarettes to low-risk, noncombustible products. The minimum tax levels envisaged in leaked proposals are far greater than would be implied by the difference in risk compared to cigarettes. If the excise regime were more proportionate to the risk, the tax take would be outweighed by the costs of tax administration, and it would barely be worth raising excise duties. Member states should insist on their right to set zero minimum taxes on noncombustibles as it is their right to pursue tobacco harm reduction domestically. There would also be a scope for setting maximum tax levels for safer products to maintain a material difference in taxation between the highest-risk products and lowest-risk products.

Fifth, the EC plans to make it harder for European citizens to learn of safer alternatives to smoking by imposing further controls on advertising and promotion and possibly to willfully mislead consumers with packaging and warnings that implicitly exaggerate the risks of low-risk alternatives to smoking. Again, the regulatory tactic is to treat all products as if they are as harmful as cigarettes when what is required is more nuanced risk communication. If the EU follows the direction of the WHO, it will risk drifting into inappropriate restrictions on free speech and legitimate opinion.

The question for me is why? What fearful autocratic reflex causes the EC to suppress pro-health innovation and see opportunity as a threat? There is an opportunity here for the free movement of goods and services within a well-functioning internal market to deliver a high level of health and consumer protection. The internal market, if allowed to function as intended, could end the cigarette era and epidemic of smoking-related disease. Yet its most ardent champion, the EC, appears unwilling to let the internal market crush the cigarette trade through the power of consumer preference, competition and creative destruction. What a pity.