Five types of innovation

By Clive Bates

Where does innovation in the tobacco and nicotine field come from? Is it the far-sighted senior executive assessing the needs of the evolving market and committing R&D budgets to realize the corporate vision? Or is it the genius scientists and engineers toiling 24/7 in the labs to invent the wonder product that will become The Next Big Thing?

Both are caricatures, of course, but neither explains how innovation really works.

In his brilliant book, How Innovation Works, author Matt Ridley points out that “Innovation is not an individual phenomenon but a collective, incremental and messy network phenomenon.” For those involved, I would say it is more like surfing while juggling than a straightforward path from idea to implementation. To see why, let’s look at five types of innovation in the tobacco and nicotine market.

First, disruptive innovation. The most prominent recent case of disruptive innovation in the tobacco and nicotine field is the rise of electrical heating as an alternative to tobacco combustion to create an inhalable nicotine-bearing aerosol. Though the Chinese inventor Hon Lik is usually credited with inventing the e-cigarette, the truly disruptive innovation came before and from outside the tobacco and nicotine industry. It is what makes the e-cigarette and modern heated-tobacco products possible. The critical disruptive innovation was the lithium-ion battery. By the 2000s, battery technology had steadily progressed to achieve a sufficiently high power and energy density, allowing rapid heating and an adequately long life between recharges within a compact form factor. Developments in battery technology were driven by the demands of the giant and ultra-competitive markets for mobile devices like smartphones and tablets.

For decades, the intense heat, complex reactions and chemical cocktail generated by the combustion of tobacco leaf at 900 degrees Celsius in the burning coal of a cigarette were unmatched and unmatchable as a means of delivering nicotine to the lungs. The combination of electrically heated coil and e-liquid to generate an aerosol is now competitive. The disruption of the dominance of the cigarette, currently underway and likely to last two decades to three decades, is driven by a fundamental energy transition that degrades the advantage of combustion.

I refer to the second type as system innovation. This is the consequential economic, regulatory and public health reaction to the initial disruption and may involve hundreds of innovative responses. For example, the emergence of e-cigarettes triggered a creative response in the Stop Smoking Service in the city of Leicester, U.K. Under the leadership of its manager, Louise Ross, the service changed its practice to embrace vaping as a low-risk alternative to smoking that could appeal to many smokers who had previously been beyond the service’s reach. Through the power of example, that experience led to further innovation at the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training and with the government’s support to guidance on e-cigarettes issued by the National Health Service.

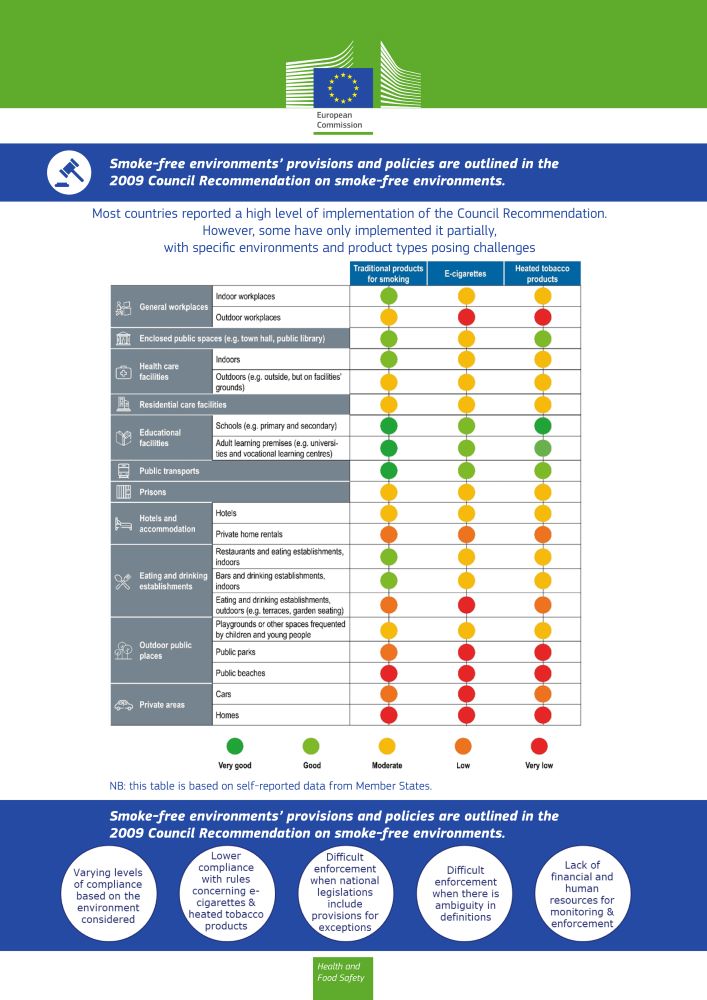

But this innovation did not happen linearly, driven only by personal inspiration. It is best seen as “emergent,” arising from a wide range of concurrent changes and influences triggered within the public health ecosystem. The disruptive innovation also led to system innovations in regulation, such as the 2014 European Union Tobacco Products Directive. In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s deeming rule brought vaping products into the definition of tobacco products and under the jurisdiction of the Tobacco Control Act. The initial disruptive innovation also led to innovation in the business models of tobacco companies, but also in the tactics of their traditional adversaries. Tobacco companies started moving their business toward a future in noncombustible nicotine products, and the anti-tobacco groups shifted their focus from preventing disease to fighting nicotine addiction.

For tobacco and nicotine companies, the disruptive innovation and the system responses it triggers are like a “big wave,” both prized and feared by top surfers. Like a wave, the companies didn’t create it and can’t control it, but their challenge is to catch it, ride it well and not wipe out. The case of Kodak and its destruction under the breaking wave of digital photography is probably the most cited case of an innovation wipeout. But it doesn’t have to be a technology shift. In the 1970s, deregulation in the aviation sector enabled the emergence of the innovative low-cost airline business model. It wasn’t long before major airline incumbents were going under as that big wave gathered pace.

The disruptive and systems innovations generate a changing paradigm: a big wave of opportunity or destruction that businesses must learn to surf. But why does innovation feel like juggling while surfing? The juggling reflects the frenetic activity of keeping a company moving, in financial balance and ahead of its rivals while it navigates a radically changing context. This brings us to three further types of innovation: the innovation occurring within the changing paradigm.

So, the third type of innovation is evolutionary. It resembles the Darwinist process of evolution in nature. Here, the consumer provides what evolutionary biologists call selection pressure, and innovation emerges from incremental improvement through trial and error, mirroring what biologists recognize as mutation and natural selection. It will usually be incremental, but its impact will not always be gradual. Evolutionary innovation can make radical inroads into a market by solving a particular problem or exploiting an opportunity.

A good example is pod-based vaping products using nicotine salts. Salts change how nicotine is absorbed in the airways and allow users to consume smaller volumes of higher strength liquids. The effect of the salts is to allow high-strength nicotine liquids to be used without undue harshness with a smaller battery and tank, enabling a compact and convenient device. This addressed the challenge of providing a convenient and discreet product with effective nicotine delivery. It was wildly successful—at least where regulators allowed it.

I have seen much handwringing about the recent rise of disposable vaping products. But this is another case of evolutionary innovation. The disposables solve the problem of finding a quick and convenient way into vaping for smokers in the early or tentative stages of switching away from smoking. They are simple to use, low cost and convenient. They don’t require an upfront investment in a device, so they lower the cost of consumer trial and experimentation. Like many innovations, these products have downsides, such as the waste generated. But this is manageable and must be set against the potential benefits and in context with other waste material flows.

The fourth type of innovation is adaptive. This is a variation of evolutionary innovation, but it arises in response to regulation. Ultimately, it is driven by meeting consumer preferences, but it is triggered by regulatory interventions that would otherwise compromise the consumer experience—ether by design or as an unintended consequence. One example is the mentholation cards that emerged after the European Union ban on menthol-flavored cigarettes. These are inserted into cigarette packs to infuse nonmenthol cigarettes with menthol flavor. Another case is the “shortfill” e-liquid containers that became popular as a workaround to overcome the European Union ban on e-liquid containers of more than 10 mL volume. Much larger containers of nicotine-free vaping liquid are sold only partially filled, allowing the nicotine to be added later—often from nicotine liquids stronger than permitted in the EU.

As the FDA imposed ever more burdensome regulation on nicotine vapes, small companies introduced synthetic nicotine products because the law confined FDA jurisdiction to nicotine derived from tobacco. This example also illustrates the arms race fought between adaptive innovators and responsive regulators. By March 2022, the FDA had prompted Congress to amend the Tobacco Control Act to apply to nicotine derived from any source, not just tobacco. Adaptive innovations can come with novel risks. For example, regulated bans on flavored e-liquids may lead to consumers adding food or aromatherapy flavoring agents not necessarily intended for vaping.

The fifth type of innovation is user-driven. The early vaping enthusiasts were hybrid producer-consumers, interacting on user forums with a strong problem-solving ethos and a hands-on approach to product design and construction. Users created innovations like “squonkers” or “squonk mods” to facilitate dripping, a niche style of vaping, by incorporating a flexible liquid bottle into the design of the vaping device. But the most impressive innovations from the user side have been social and community in nature. The vaping forums and vape meets created an elaborate technical and moral support infrastructure. This online community blossomed into vape shops as centers of expertise, personalization and encouragement. The vape shops are now de facto cutting-edge stop-smoking services but with a very different offer to the more clinical settings of traditional services. Even the biggest corporate beasts benefit and learn from user innovation. They should take care not to crush it.

Innovation is a fluid and dynamic business phenomenon with many simultaneously moving parts embedded in an unpredictably evolving, threatening or promising context. Surfing while juggling is hard and risky, but it is no longer a choice in the tobacco and nicotine business.