Sub-par production materials and user error are the main causes for battery failure.

By Timothy S. Donahue

Batteries can be dangerous. Cellphones, laptops, hover boards and drones all had battery issues in the early stages of their development. This is true for the vapor industry, too. Cheaply made products, improper use and misinformation have been the cause of several well-publicized accidents.

In April, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) held a public workshop centered on battery safety concerns in electronic nicotine-delivery systems (ENDS). The event was moderated by Matthew Holman, the director of the FDA’s Office of Science at the Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). He said the FDA has been collecting data and information on explosions, fires and overheating of vapor products for some time.

“However, additional data and information would significantly help us better understand these products and how to regulate them in order to minimize this acute public health concern,” he said. “That is why we are here today.”

Holman emphasized that the FDA intends to use the information presented and discussed during the workshop, as well as ongoing research efforts, to help inform future regulatory actions and decisions related to these products. “[The] FDA makes decisions based on science, and we’ll use the best available science to inform regulations,” he said.

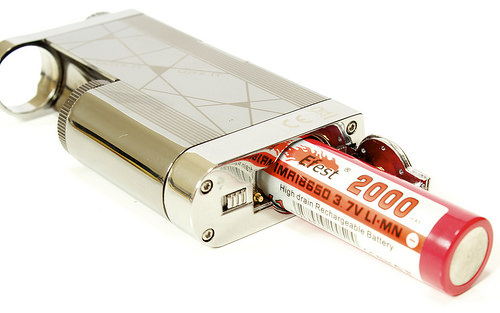

The “outcome” of the conference can probably be best summarized in two statements: Using high-quality batteries is a necessity for safety, and, if used properly, batteries rarely cause harm. Kevin White, an electrochemist with Exponent, an engineering and scientific consulting firm, told attendees that there are about 100 billion lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries in use today, depending on which market analyst you believe. “So there is a lot of money to be made, and a lot of folks are trying to get their hands into the pot,” he said. “Some are making very nice lithium-ion cells, and some are making questionable lithium-ion cells, and that, again, is a problem.”

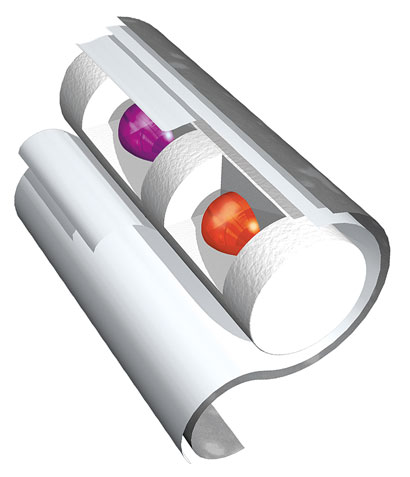

Vapor products wouldn’t be possible without li-ion batteries. Neither would laptops, cellphones or many other devices as we know them. “Lithium ion is a game changer; that’s for sure,” said White. “It’s a technology that puts a lot more power into a small space than we’ve ever been able to do before, and it’s one of the things that enables these nicotine delivery devices to work well. But it is not without risks, and it can be a very safe product if those risks are understood and mitigated. And the industry is maturing to the point where that is possible and could be so for this particular application as well.”

White said li-ion batteries were first commercialized in 1991. “It’s a fledgling industry, but they’ve gained incredible traction because they are so much better at storing energy than most of the … well, all of the other chemistries that are commercially viable,” he said. “Therein lies the problem. You’ve got a whole bunch of energy in a very small space, and if it comes out in an uncontrolled fashion, it can be a devastating consequence.”

Data default

Drawing on information from news sources and the limited e-cigarette fire data that the federal government began tracking in 2015, Lawrence McKenna from the U.S. Fire Administration found 195 discrete incidents of explosion or fire involving ENDS devices worldwide from 2009 through 2016. “The vast majority of the incidents … came out of the media,” he said.

McKenna found no reports of e-cigarette battery-related deaths in the U.S. There was one death reported in the U.K., but that one had less to do with the ENDS device than it did with the medical device that was being used simultaneously. The victim was vaping in an oxygen tent.

Some 60 incidents occurred while the device was in the user’s pocket, hand or mouth, according to McKenna. Forty-eight incidents happened while the device was being charged. Eighteen incidents were “in storage”—in a purse or on a countertop, for example. The cause of the remaining occurrences was not specified.

McKenna said there were 38 severe injuries (requiring hospitalization), 80 moderate injuries (treated in an emergency room) and 62 incidents where no injuries were reported. Fifteen incidents resulted in minor injuries.

Felicia Williams, a burn surgeon affiliated with the University of North Carolina, blamed e-cigarette batteries for an increase in devastating injuries. She showed several pictures of e-cigarette battery burn victims. During a recent American Burn Association conference, she learned that approximately 70 people suffered injuries from vapor products serious enough to warrant surgery, with most of those happening in 2016. “These are patients that required surgery, not the number of patients that have presented to our clinics,” she said. “You’re talking about 100 patients overall that present to the different clinics with minor injuries that don’t require hospital admission.”

To put the number of injured users into perspective (although that was not Williams’ intent), Williams noted that there are more than 9 million ENDS users in the U.S. She also stated that a recent change in medical codes for injuries has made it difficult to delineate whether somebody had been burned by a flame, a chemical or a vapor product battery.

Standard issue

Battery safety concerns are not specific to vaping products, according to Patricia Kovacevic, general counsel and chief compliance officer for Nicopure Labs. She told attendees that the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission recently pointed out issues with safety standards for lithium-ion batteries, following a massive recall of Samsung phones.

“When people say we don’t have battery standards—actually, we do,” she explained emphatically. “They’re not being applied in the U.S., and they’re not mandatory at this time. [The] FDA has authority to issue product standards. The development and use of standards have been integral to the execution of the mission of [the] FDA since its establishment. These are the very words of the FDA on their own website.”

Several speakers called the battery business for vapor products the Wild West. Eddie Forouzan, an electrochemist with Artin Engineering and Consulting Group, said the typical safety tests for Li-ion batteries are only meant to verify the design. “That’s another critical point that I think we all need to understand,” he said. “It is impossible to manufacture a lithium cell or integrate systems-engineered lithium cells in a product and expect to have a 100 percent safe product with zero failures.”

Finances factor in production, too. Forouzan said that some companies, in an effort to save money, buy or source lithium cells from no-name brand manufacturers that use stainless-steel razor blades to cut their electrodes. “So fundamentally, we’ve seen a lot of cases that have to do with cheap, cheap, cheap stuff that’s being used—heap components on the electronic circuitry or cheap manufacturers of lithium cells, relatively unknown sources. Again, that’s a key factor,” he says. “When there’s a name brand to protect, at least they try to protect it. Bottom line: Don’t buy junk.”

Douglas Burton, from Altria Client Services, said that, in the absence of standards in the development of these e-cigarettes, there has been little guidance on what constitutes a safe device. “We need standards,” he said. “If we don’t have them, we can expect to see the same type of reports that we are currently seeing for adverse events. Good manufacturing practices can improve manufacturing quality.”

The main reason for battery failures, however, is the end user. Forouzan said that, especially with ENDS products, failures are most commonly related directly to the heating coil. “Now, it doesn’t mean that the heating coil is heating the cell for it to fail, but it’s because the heating coils are messed around with by the end user,” he says.

User error

Most speakers agreed that proper use is vital to battery safety. Williams claimed that less than 1 percent of ENDS battery injuries occurred while the device was charging. “So they were either in use or in their pockets, and the overwhelming majority of these injuries had been while they’re in a user’s pocket,” she said.

The environment in a pocket is conducive to explosions, according to White. But contrary to what some might believe, it’s not due to static electricity. “It’s the fact that you have keys and coins and things like that in your pocket,” said White. “I mean, in an 18650 cell, the separation in the top cap between the positive portion of the cell and the negative portion of the cell is very small,” he said. “So if you have something conductive in your pocket and the protective sleeve that’s around the cell is compromised, you can cause a short circuit to occur in your pocket, and you get heating because of that.”

Spike Babaian, technical analysis director for the New York State Vapor Association, said the majority of the incidents that cause e-cigarette explosions are because people take loose batteries and put them in their pocket with metal keys and change. “This is a huge deal,” she said. “Another mistake that is frequently made is using the wrong charger. People take a battery that is in an e-cigarette, and they go, ‘Well, it fits into this charger, so I’m going to use this charger, even though I bought this charger at a gas station or airport or wherever.’”

McKenna said many vapor devices come with a USB port for charging and people will plug them into any USB port they can find. “Whether it’s in their automobile or their computer or their laptop computer—and not all USB ports produce the same amount of voltage,” he said. “And we were seeing with some of the lower-end devices overcharging incidents when you plug a device in that’s meant for 3 volt or 1 volt charging and you plug it into a 3 or 5 volt USB port, and you overcharge the device.”

The speakers agreed that consumer education is vital. John DeLeeuw, SMS (safety management system) manager for American Airlines, used a vape shop he visited as an example of a process for educating ENDS consumers. He said the shop had cards they would distribute when someone bought a battery.

The cards contained warnings such as “Keep your batteries in approved battery cases when not in use,” and “Don’t keep your batteries in your pocket, purse or other receptacles with loose change or keys.”

Babaian’s shop provides a free battery case with all loose batteries.

To some participants the discussion was unnecessary. They felt the FDA shouldn’t be regulating batteries in the first place. Amy McCann, with the Smoke-Free Alternatives Trade Association (SFATA), says her organization opposes battery law proposals if they single out vapor products from other devices, like cellphones and laptop computers, for enforcement.

“Proper storage, charging and use patterns are important practices for all batteries that consumers should understand,” she said. “SFATA also opposes defining batteries as a tobacco product and regulating them as such simply because they can be used to power a vapor device.”

Kovacevic said the FDA may be overreaching in its attempts to regulate batteries and maybe that should be left to a different government agency, such as the Consumer Product Safety Commission.