When scientists work for a tobacco company

By Cheryl K. Olson

Carlista Moore Conde never expected to work for Big Tobacco. A chemical engineer by training and a former NASA scholar, her career had focused on R&D for multibillion-dollar brands of household name consumer goods at Procter & Gamble.

“I spent 20 years working on products that improved people’s lives,” she told me soon after we’d met at the 2021 Global Tobacco and Nicotine Forum in London. “Now I’m working on products that can save lives.”

As group head of new sciences at BAT, Conde is part of a trend among tobacco companies to hire from outside the fold—industries that often have nothing to do with nicotine, as well as academia and government—to work on reduced-harm products that lower the health risks to people who are already addicted to combustible cigarettes.

“I have family members, dear aunts and uncles, who spent a lifetime smoking and suffered the [health] consequences,” she continued. “So I never even considered working for a tobacco company, honestly. I misperceived the harm of alternative nicotine products as being the same as traditional smoking.”

Mohamadi Sarkar took a different path to working in the industry. He’d been a professor of clinical pharmacology at the Medical College of Virginia at Virginia Commonwealth University where he’d done research on smoking-related diseases. He was approached by scientists from Altria about joining them after he’d presented at a conference run by the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

“And my first reaction was ‘Heck no!’” he said. “I was a tenured professor. Never in my wildest dreams had I thought I’d work for corporate America, let alone work for a tobacco company!” He’s now a fellow in scientific strategy at Altria Client Services. Sarkar has been at the company and its predecessors for 19 years. He maintains a faculty appointment at VCU and teaches three courses there per year.

Brian Erkkila was a neuroscientist at the National Institutes of Health before joining the then-new FDA Center for Tobacco Products in 2011. He was a lead toxicologist there for more than six years. After a three-year stint at the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, he moved to Swedish Match in 2021, where he is director of regulatory science.

“It was certainly comforting to see how ‘all-in’ everyone I work with at Swedish Match is about tobacco harm reduction,” he said. “Looking out from inside the industry, there is a magnified sense of uncertainty concerning the regulatory environment. It’s very difficult to know what the nicotine marketplace will look like even one or two years from now.”

(Photo: Seventyfour)

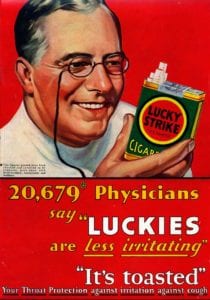

New Scientists, Old Beliefs

A generation ago, the tobacco industry was largely an old boys’ network. Tobacco was “in your blood.” As the health effects of combustible cigarettes became apparent, many scientists from outside that industry saw joining it as a career killer.

But Big Tobacco has moved on. In response to public health findings, combined with social, regulatory, and economic pressures, it’s shifting away from combustible tobacco and focusing on alternative, less harmful nicotine-delivery systems. Still, scientists who are recruited from outside the industry often respond with healthy skepticism about whether this new focus is sincere. Conde shared that skepticism until she spoke with BAT employees who had come from outside tobacco and took a close look at the company’s operations.

“You hear stories about big bad tobacco from the past,” she added. “But what I found is that the science done here is done in a very transparent and rigorous way and is shared, even with our competitors.”

Erkkila added, “Sadly, I feel that some former colleagues will simply write me off for joining [the] industry. However, they need to understand that this is not the same industry from decades ago. FDA regulation of tobacco products has ensured that the research being done by companies is vetted and carried out in a robust manner.”

Sarkar admits that he struggled a bit with the reactions of some people at his university when he started at what was then Philip Morris USA. “Folks I knew from my past experience in academia who were my friends and colleagues started distancing themselves,” he recalled. “They were not happy with my decision to work for a tobacco company. But we do good science with the right rigor. I take great pride in the work we do.”

For Sarkar, as well as other scientists who’ve worked previously as professors, one of the strong advantages of corporate research is the consistency of funding. Another is the speed with which a novel idea can be pursued. Research grants to university laboratories often require months of detailed paperwork. The success rate of scientific research grant applications to the federal government—the largest funder of such research—is notoriously low. (In 2020, the National Cancer Institute rejected six grant applications for every grant that it funded.)

“At PMUSA, I was just amazed at the resources available to do the research, and the commitment not only to conduct the research but to publish and share it with the scientific community,” Sarkar continued. “Unfortunately while we are keen on publishing and sharing our research, some journals don’t accept industry funded research for peer-review consideration. In this situation, nobody wins—not science, not good policy, and certainly not adult smokers.”

A Caste System for Researchers?

There’s a paradox to the resurgence of suspicion and even outright rejection of industry-conducted science on tobacco harm reduction and alternative nicotine products. While the tobacco industry engaged in questionable and even spurious research a generation or two ago, its recent approach has been quite different.

“In this age of rampant misinformation, certain groups ignoring quality science because they don’t like the source strikes me as a hindrance to public health,” said Erkkila.

Recently, the editorial board of Nicotine & Tobacco Research, the journal published by the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, announced that “In order to continue the journal’s policy of alignment with the SRNT, which owns the Journal, N&TR will no longer allow tobacco industry (TI) employees to submit work to the journal in any format. TI employees include those individuals who work for companies owned in part or in whole by manufacturers of commercial tobacco products.”

This concern flies in the face of one of the fundamental tenets of scientific research: that it should be judged solely on its rigor not on the provenance of the researchers. That is the purpose of anonymous peer review. Preemptively excluding all research from the industry (or academia or government or pharmaceutical companies) is naive at best and will likely do harm to the public health.

All researchers who publish should cite both their affiliations and their sources of funding as well as other potential conflicts of interest. This encourages readers to employ a gimlet eye when considering conclusions and recommendations. It’s a pretty safe bet what the National Pork Producers’ Council will recommend for dinner. But does that mean I should automatically reject its nutritional analyses or its studies of African Swine Fever risk and prevention?

The new policy draws some bizarre distinctions. I’m a former academic researcher. During my career, I’ve worked on tobacco harm reduction and youth smoking prevention projects that were funded by government, nonprofits and industry. Am I a “good guy” or a “bad guy?” Is there a formula by which a certain amount of government-funded research cancels the stigma of industry-funded research, the academic equivalent of buying carbon offsets? (I’m only being slightly facetious.)

Note that the SRNT definition of “tobacco industry” does not include e-cigarette makers, except those linked to traditional tobacco product companies. (It also does not exclude consultants to tobacco companies from its conferences or journal, only industry employees.)

We run the risk that some of the “bad actors”—companies that have shown scant interest in harm reduction and youth use prevention—will have access to communications channels being denied to “good actors” that currently or have previously manufactured tobacco products. Under these rules, researchers for companies side-stepping Food and Drug Administration regulation by using synthetic nicotine could have their work considered for publication while scientists who crossed from government and academic posts to Juul (which is partially owned by Altria) would have their work summarily dismissed.

Simplistic approaches such as this may feel righteous, but they elevate form over function. We lose sight of the ultimate goal—a goal more likely to be achieved by sharing data and resources. Many scientists who have entered the industry believe that they can do more to block the dangers of combustible tobacco from the inside than from the outside.

“My moves from regulator to the Foundation and ultimately to Swedish Match have all been about reducing the public’s harms from tobacco,” said Erkkila. “Others’ view of me may have changed, but these moves have allowed me to appreciate the issue from many sides.”