The market for tobacco and nicotine is transforming—how could it look by 2040?

By Clive Bates

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future,” said the great Danish physicist Niels Bohr. The future is a burial ground for expert reputations, but that should never be a reason to shy away from predictions. Much of what we do today will shape the world in 2040, and our view of how the world should be in 2040 should shape what we do today. So let us consider the evolution of the market for tobacco and nicotine products out to 2040. There’s a lot to think about, so buckle up!

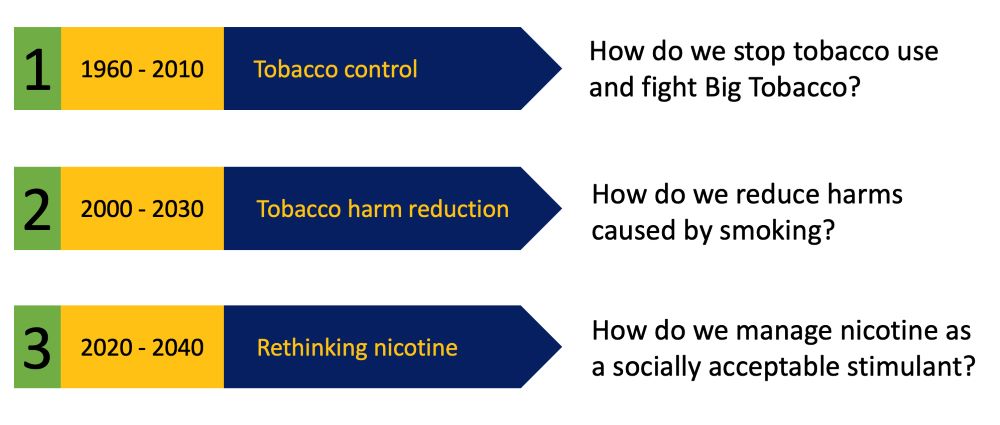

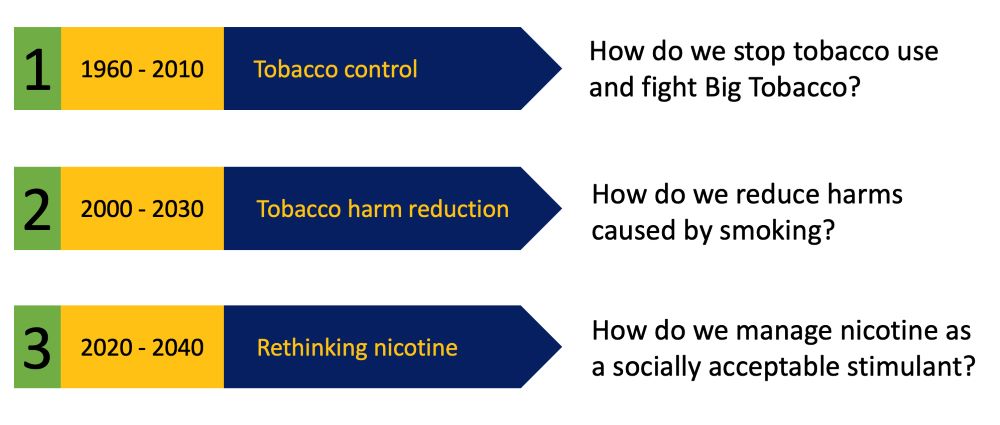

First, three epochs. I see the evolution of the tobacco and nicotine policy as three overlapping epochs covering 1960 to 2040.

(1) The tobacco control epoch stretched from 1960 to 2010. It was triggered by reports from the U.K. Royal College of Physicians and U.S. Surgeon General. It involved an all-out struggle between public health and the tobacco industry over the multiple harms of cigarette smoking, culminating in the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, agreed in 2003.

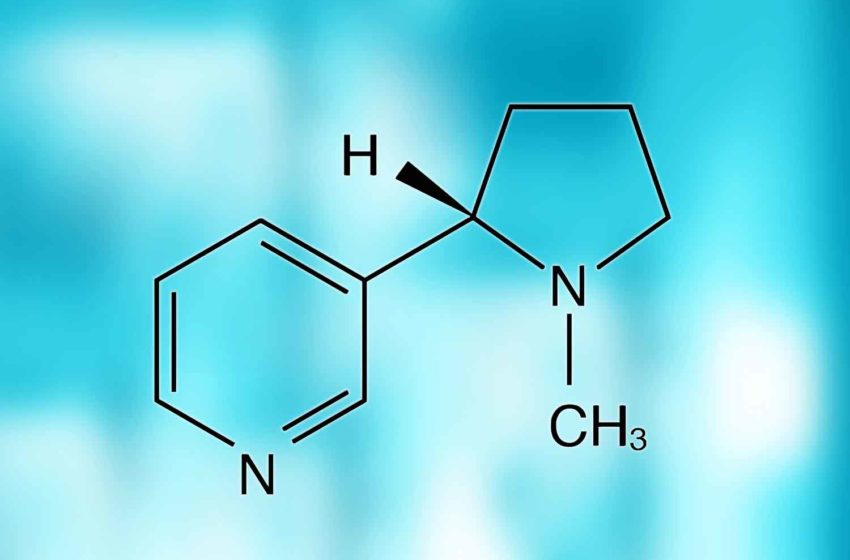

(2) The tobacco harm reduction (THR) epoch started around 2000 with the increasing recognition that smokeless tobacco, especially Swedish snus, was much safer than cigarettes and could displace smoking. That epoch took hold in 2010 with the rise of vaping, then heated tobacco, and now nicotine pouches. The THR controversy is focused on reducing the harms associated with smoking and exploiting (or resisting) a massive public health opportunity (or risk). However, this is an interim phase.

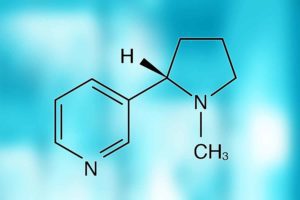

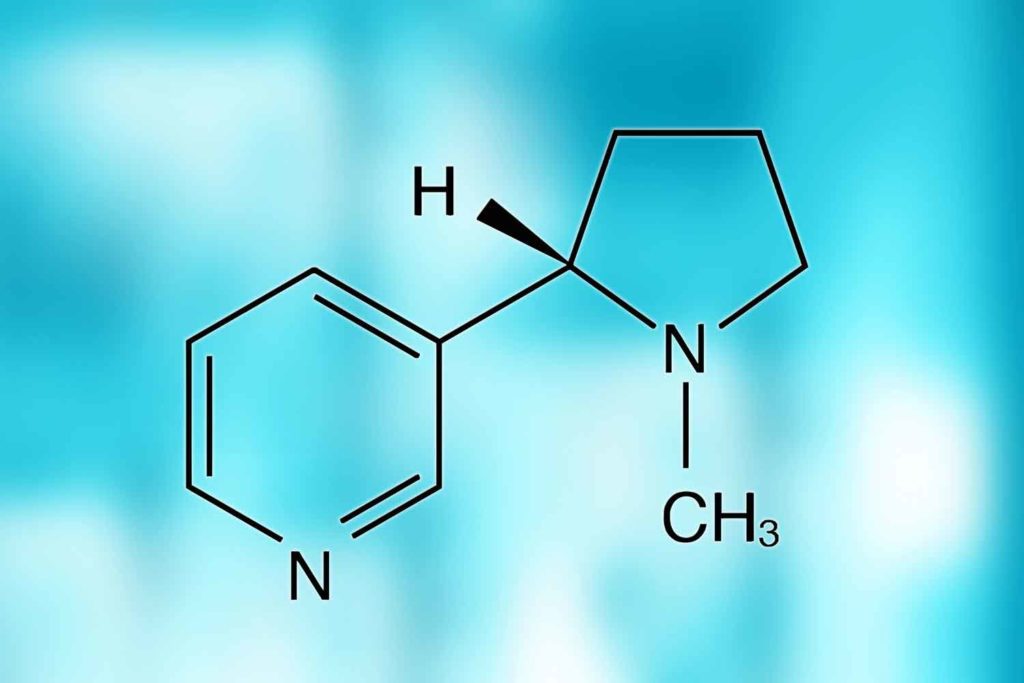

(3) The rethinking nicotine epoch is already underway and beginning to shape thinking about the future. We will need to confront the fundamental question: What is the place of nicotine in society? What does nicotine use mean if few people are smoking and there is not that much harm to reduce? This is already a live question; around half of American vapers aged 18–24 have not previously smoked, though some might have smoked had there been no vapes. We will undo the deep conflation between the relatively benign stimulant nicotine and the harms of smoke inhalation and place it alongside caffeine, alcohol and, increasingly, cannabinoids as legal recreational substances.

Second, the persistence of the demand for nicotine. Many tobacco control activists have hoped that the relative decline in cigarette smoking would also eventually lead to a nicotine-free society. However, they misjudged the underlying behavioral drivers. The decline in smoking was driven by the harm to health and welfare, reinforced by policy-induced pain, such as taxes, smoking restrictions or “denormalization” designed to create a deterrent to uptake and motivation to quit. However, without the underlying harms, the deterrents are greatly weakened, and there is no justification for a punitive, coercive and stigmatizing policy. We are left to answer the question: Why is there a demand for nicotine? The demand derives from a simple proposition: For some people, nicotine use makes them feel or function better. Looking out to 2040, we should see the demand for nicotine as robust and resilient. The demand for any particular way of taking it is much more fluid or, as economists say, “elastic.” In fact, without the harms of smoking and related deterrents, demand might increase. That may seem unnerving, but should we care if the harms are low or negligible? As a 1991 Lancet editorial put it: “There is no compelling objection to the recreational and even addictive use of nicotine provided it is not shown to be physically, psychologically or socially harmful to the user or to others.”

Third, technology and innovation. Can smoke-free nicotine products entirely replace smoking to meet all nicotine demand? Many smokers have tried the alternatives and chosen not to switch. There is more to smoking than nicotine self-administration, including the speed and peak of nicotine delivery, other psychoactive agents, sensory experiences such as “throat hit,” flavors and aromas, behavioral and ritual aspects, and perhaps deep brand loyalties that reach right into the individual’s identity. However, the pace of change in alternative technologies has been extremely rapid since the emergence of cigalike vapes at a noticeable scale about 15 years ago. Imagine the product landscape 15 years from now. That will include better versions of the product categories we have today: vapes, oral nicotine, heated tobacco and smokeless tobacco, but perhaps also sprays, inhalers and nasal products. Who knows? Competitive innovation meets consumer demand in novel and sometimes surprising ways. Many public health commentators, and perhaps tobacco industry die-hards, believe that these products will remain a niche alternative for only some smokers. Don’t count on it. Over time, that niche will expand through innovation until it dominates the market. That trend is inevitable and unstoppable.

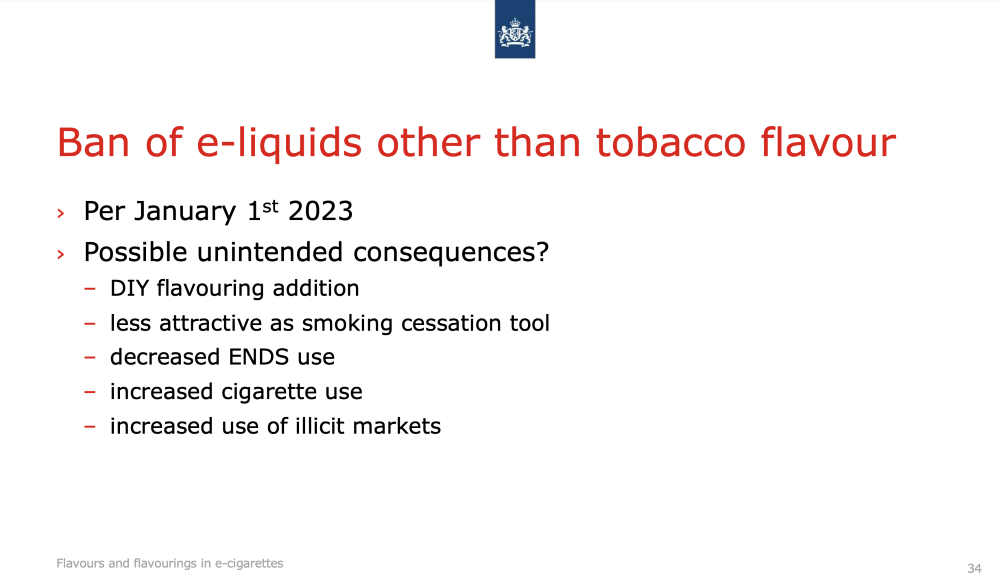

Fourth, regulation and markets. The twin forces of consumer demand and innovation will squeeze the cigarette market into contraction and lower profitability. The greatest danger is that the rise of smoke-free alternatives will be treated as a threat, not an opportunity, and be met with prohibitions or excessive regulation and taxation. Although such regulation will aim to reduce nicotine use by constraining supply, its effect will be to switch from lawful commercial supply to illicit, criminal and informal supply. This effect is already visible in supposedly strong regulatory jurisdictions like Australia and the United States, where authorized products from approved suppliers meet less than 10 percent of the vape market. Jurisdictions such as Brazil and India have imposed prohibitions, but all that means is that the regulator is missing in action along with any consumer protection. Prohibitions trigger the nasty triad of more smoking, more illicit vapes and more risky workarounds. Whatever the regulation, there will be supply. Banned products do not simply disappear. Whether the supply is lawful or illegal will become the nicotine and tobacco policy conflict of the coming decade. The market will remain lawful if (and only if) the policies adopted for smoke-free alternatives are risk-proportionate, focus on consumer protection and meet the adult demand for low-risk nicotine.

“If you had a product that addicted 45 million people and killed none of them, I would take that deal. Then you’d have coffee!”

Fifth, young people and nicotine. By 2040, a more sophisticated discussion of youth nicotine use will emerge. If we accept that adult use of nicotine will persist indefinitely, then we should expect some young people to try it, and for some, it will make them feel or function better. To the extent that youth vaping displaces smoking, it provides net benefits to public health. No reasonable person, including me, wants young people to smoke, vape or use nicotine in any form. However, it is one thing to express an opinion on what is best for young people, but it is quite another to believe this can or should be achieved by various forms of prohibition imposed on adults. Four strategies will emerge to provide reasonable protections to young people. The first will be an imperative to keep the adult nicotine market lawfully supplied and thus inhibit the formation of large criminal supply networks that will also supply youth. The second will be age-secure retailing, drawing on technology and licensing. The third will be controls on marketing, including branding, packaging imagery and flavor descriptors. Finally, we need to be candid and not hysterical in communicating the risks of nicotine use. The global public health problem is not youth vaping but the millions of existing adults who have already been smoking for a decade or more.

Sixth, the tobacco control complex. The abstinence-only tobacco control field will face a bruising contest with reality. As the wide range of negative consequences of prohibitions are increasingly visible and articulated scientifically, major funders will become wary and back away. The research funding agencies will become more skeptical. The “realists” will grow in stature and begin to prevail over the “idealists” (see “Realists and Idealists,” Tobacco Reporter, June 2024). Pragmatism will drive out hubris, and grand regulatory schemes will fall into disrepute. The original goal of tobacco control has been to address the range of serious diseases and other harms caused by smoking. But that game is up. In comments to the New York Times almost 20 years ago, the then president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, Matthew L. Myers, endorsed a world of nicotine use without significant harm: “The challenge to me is not to eliminate smoking but the death and disease from smoking,” Myers said. “That should be the end goal. If you had a product that addicted 45 million people and killed none of them, I would take that deal. Then you’d have coffee! I have to believe that if the marketplace incentives were such that over time, someone could devise a product that would give the same satisfaction as tobacco but didn’t kill them, people would flock to it.”

Then you’d have coffee! Yes, precisely. But there is no gigantic “coffee control” movement. There is no multimillion-dollar Campaign for Caffeine-Free Kids. As Myers’ statement unintentionally suggests, the tobacco control movement is profoundly threatened by nicotine use without significant harm. Without harm, it has no purpose.