What is bad science, and why is there so much of it?

By Clive Bates

Every Friday afternoon, I receive the worst email of the week. It is an automated search on the PubMed database, an index of the biomedical literature covering over 30 million published papers. The search tries to pick up new studies relevant to tobacco harm reduction and typically finds 30–70 new papers each week. Once the email comes in, I look through the abstracts and write down hot takes on the ones that seem relevant to policy or practice. Then I share with public health and consumer advocates. To be honest, it is often a dispiriting experience. Despite the scattering of excellent “must-read” papers, many are truly awful. I have been doing this since 2016, and the volume of papers has roughly doubled.

So, what have I learned by going through this painful weekly ritual? There are distinct patterns repeated in the literature, including poor methodology, poor interpretation of results and, almost always, poor extrapolation from findings to policy. There are obvious biases and sometimes near-comical desperation to find fault in reduced-risk products. Let me provide a list of some of the most common flaws.

- Poor toxicology. The 16th century Swiss physician Paracelsus coined a maxim now expressed as “the dose makes the poison.” The detectable presence of a hazardous chemical does not mean it is toxic. There must be sufficient exposure to the human body to cause harm. As an example, many studies find metal residues in vape liquids and aerosols, but usually at levels that create no basis for concern.

- Lack of meaningful comparisons. Many studies will present data on the effects of smoke-free products without context, such as a comparison with cigarette smoke, or some objective risk benchmark, such as the standards used for occupational health exposures. Without such context, it is impossible to assess whether the findings are a basis for concern or for reassurance. So, the question is always, “how much exposure, and is that a little or a lot?”

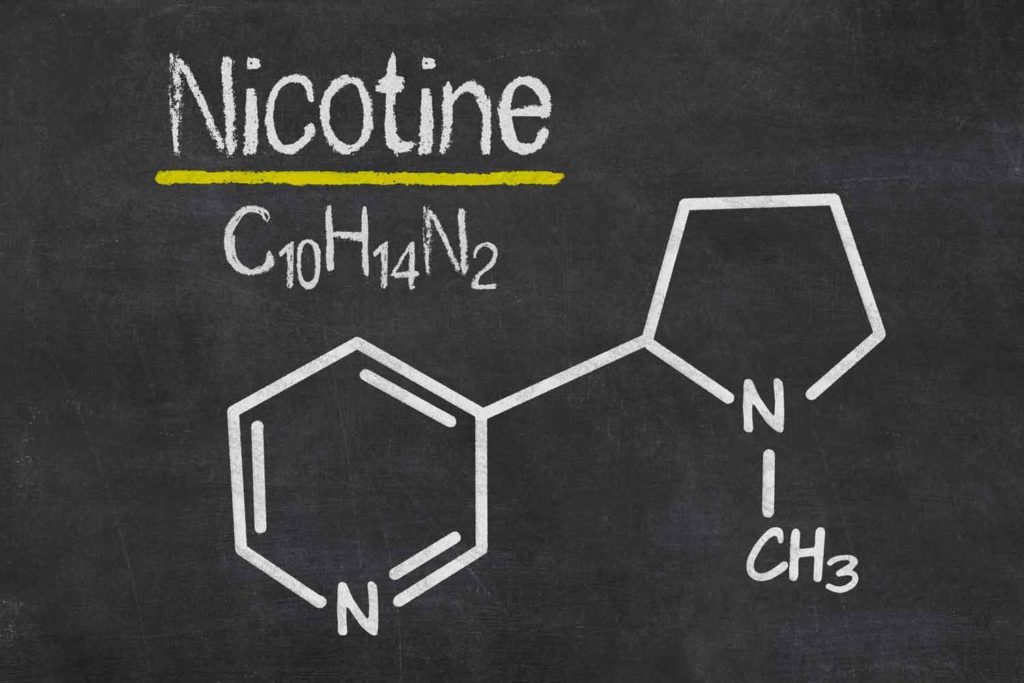

- Observations versus risks. Nicotine is a stimulant and has many effects on the body, but epidemiological studies do not generally show nicotine exposure to be harmful to health. For example, there are regular headlines reporting that nicotine can cause an acute stiffening of the aorta, the largest artery in the body. But is that bad news? It seems less disturbing when we find that coffee, exercise or even exposure to music can have the same effects.

- Unrealistic operating conditions. A range of studies makes machine measurements of emissions from heated aerosol products in unrealistic conditions that no human user could tolerate because of the terrible taste. Using this unrealistic method, researchers often find high levels of toxic chemicals. But this is about as sophisticated as testing the residues from the surface of burnt and blackened toast—and concluding that eating toast for breakfast increases cancer risk.

- Over-interpreting animal and cell studies. There are many studies of human cells tested in Petri dishes (“in vitro”), but these are tests on cells without all the defenses and regenerative capacity they have in the body. Test on animals (“in vivo”) must recognize that animals have very different physiology to humans and are sometimes bred to have vulnerabilities. In both cases, creating a realistic equivalent to the exposures a human would experience can be challenging. These studies can’t tell us much conclusively about human risk. At best, they can provide valuable clues. At worst, they can mislead.

- The wrong counterfactual. Many studies beg the question, “what would have happened if vaping did not exist?”—without that, it is hard to determine what effect vaping is having. For example, if there were no vape option, would pregnant women who currently vape be abstinent, or would they smoke? That should affect the advice of health professionals. Many are concerned about youth vaping, but for the youth who would otherwise be smoking, maybe vaping provides a significant benefit. That should affect the approach of policymakers and regulators. These assumptions are known as “counterfactuals,” and they are hidden and hard to determine, which makes them open to bias.

- Correlation ≠ causation. Many studies find a correlation (usually referred to as an association) between vaping and some harmful effect. But too many studies suggest that vaping causes the harmful effect. Take, for example, vaping and Covid-19. A 2020 study suggested Covid was abnormally high in young vapers, concluding that vaping is a “significant underlying risk factor” for coronavirus disease. But critics pointed out that people who vape may be more likely to work in occupations where they are more easily exposed. Are vapers the type of people who are more likely to ignore masking guidelines and stay-at-home mandates? These other risk factors that may be more common in vapers are known as “confounders” and are a pervasive challenge in nicotine and tobacco science.

- Reverse causation. Some studies find that vaping is associated with, say, respiratory illness. But what if some people who smoke switch to vaping precisely because their respiratory health is deteriorating? There would be an observable association, but the respiratory illness would be causing the vaping, not the other way around.

- Confounding by smoking history. There has been a recent spate of studies claiming that vaping causes heart disease or respiratory conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Almost everyone old enough to both vape and to experience these conditions has a smoking history, usually decades long, contributing to the disease. In such studies, it is impossible to isolate the effect of vaping from smoking. In some cases, the vaping has even commenced after the event or diagnosis.

- Misunderstanding gateway effects. Does vaping lead to smoking? If that were the case for significant numbers, vaping could be almost as harmful as smoking. There are studies that show that young people who vape are also more likely to smoke. But that does not mean the vaping causes the smoking. More likely, the characteristics of the individual (e.g., rebelliousness) or their circumstances (e.g., parents, peer group) incline them to both smoking and vaping. This is a rival explanation to the gateway effect and is sometimes known as the “common liability” theory.

- Selection effects. Some studies will focus on people who are unusually dependent on nicotine and therefore find it harder to quit. For example, in some cases, it is more likely that vaping will be tried by people who have not succeeded with any other method. This doesn’t mean vaping is less effective, just that the people using the products find quitting harder. This is a common error in studies of concurrent vaping and smoking, often known as “dual use.” The dual users are more dependent and tend to be more intense smokers with higher toxic exposures.

- Weird study populations. Not all studies conducted on social media are useless, but most are. The people discussing vaping or smoking on Twitter or Facebook are not representative of the vaping and smoking populations. Their views are not gathered systematically in the way surveys work. Trends over time might be helpful, but most snapshots tell us little.

- Baseless policy conclusions. Policy conclusions like “ban e-cigarette flavors to protect kids” are disappointingly common in the literature. To justify a policy requires numerous considerations that will go beyond the findings of any single data paper and stretch into economics and ethical considerations. Such considerations would include, for example, the assessment of unintended consequences (will kids smoke instead?) and trade-offs (between the interests of teenagers and adults).

Such a list does not explain why there is so much bad science, given these errors are simple to understand and mostly avoidable. I believe the answer lies in the incentives of those doing the science. Major U.S. federal research funders are aiming for a “world free of tobacco use,” which also means free of nicotine use. Tobacco regulatory science funded by regulators will be inclined to find justifications for regulation and intervention, not liberalization. There could also be deeper drivers: without the significant harms of smoking, there isn’t much justification for the whole field of tobacco control. Perhaps the emergence of much safer smoke-free nicotine products threatens livelihoods, careers and entire university departments, and bad science is the reaction. Maybe researchers gain prestige from alarming media coverage. These are all subtle conflicts of interest that are never acknowledged or recognized, yet they are pervasive drivers of bias.

It will surprise some, but I have noticed that science from the tobacco industry rarely crosses these lines. That is also down to incentives. The tobacco and nicotine industry must satisfy skeptical regulators about the safety and effectiveness of its next-generation reduced-risk products. It conducts research for product stewardship reasons and, in part, to take precautions against product liability litigation. The industry is incentivized to do good science.

It is time to address these problems by establishing a more constructively challenging environment for tobacco and nicotine science. This is not just an abstract academic curiosity. Public health credibility and the lives of millions are at stake.