Tobacco harm reduction is gaining momentum but continues to face many hurdles.

By Stefanie Rossel

“Tobacco harm reduction: Here for good“ was the theme of this year’s Global Forum on Nicotine (GFN) conference, which took place in Warsaw June 16–18, 2022. Around 50 speakers and panelists discussed the issues that will determine the future of safer nicotine use and tobacco harm reduction (THR). The meeting was preceded by a day of satellite events and once again featured the International Symposium on Nicotine Technology, which highlighted the latest technological advances in the rapidly changing nicotine delivery landscape.

Two hundred years after the first snus brand was launched in Sweden and almost 20 years after the Chinese pharmacist Hon Lik invented the modern electronic cigarette, THR continues to face challenges. While THR is making good progress in high-income countries, low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), where about 80 percent of global tobacco users live, are mostly excluded. In India, for example, where smokers of bidi cigarettes and consumers of hazardous oral tobaccos such as gutka represent 85 percent to 90 percent of tobacco users, bidi packs do not even carry health warnings. While gutka is officially banned, prohibition is not enforced. Instead, health authorities focus on the harms of vaping. Although vape products are banned in the country, they are readily available on the black market.

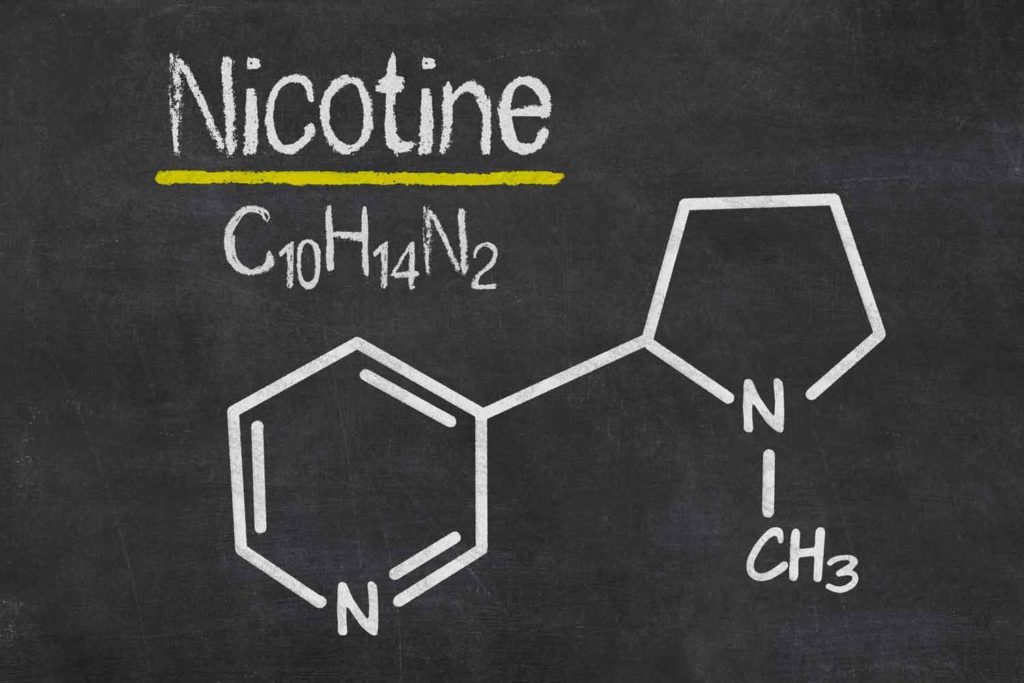

Thailand legalized the cultivation and consumption in food and beverages of cannabis in early June but continues to prohibit vaping under strict penalties. Vapers risk a jail sentence of up to 10 years. An observational study in South African hospitals not only demonstrated that inpatients had a lack of knowledge of nicotine-replacement therapy (NRT) but also that doctors in LMICs are often not trained to explain to patients how to use NRTs. Research comparing THR in Russia, China, Indonesia and India found that once smokers have understood that combustible cigarettes are harmful, the key challenge is changing behavior. In Russia and China, consumers are generally aware of reduced-risk products (RRPs) whereas in India and Indonesia, nicotine is considered the most harmful constituent, and few people know that RRPs exist.

Uncontrolled Influence

Most LMICs have ratified the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which takes a dim view of vaping. This position is backed by one of its largest donors, billionaire and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg. In his keynote presentation, journalist Marc Gunther demonstrated that philanthropy is an excise of power that requires scrutiny.

By pumping millions of dollars into nonprofits and anti-vaping groups worldwide while funding university researchers, a media initiative and a nonprofit health consultancy through the Bloomberg Philanthropies foundation has created an effective global anti-vaping campaign that is not driven by science, according to Gunther. For example, The Union a Bloomberg-backed nongovernmental organization headquartered in Paris, recently published a paper calling for a ban on all e-cigarettes in LMICs. Most damaging, Gunther said, was the relationship between Bloomberg and the WHO, which the billionaire has generously funded with many millions of dollars for a variety of projects, including $5 million for its tobacco work in 2019.

While few countries ban RRPs outright, the products often face prohibition by stealth. This month, Germany started applying a tax to e-cigarettes, which came on top of the previously applied value tax. With e-liquids now being taxed by volume, their price has almost doubled, which prevents smokers from switching as it conveys the impression that a product taxed so high must be equally as harmful as combustible cigarettes.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration picks the winners and losers through its tobacco product authorization process with little regard for consumers. The agency’s requirement for comprehensive scientific documentation of a product’s contribution to the protection of public health represents a hurdle that only the largest and most amply funded nicotine companies can manage.

Prohibiting elements that make vapor products appeal to smokers, such as nontobacco flavors, are also a kind of stealth prohibition that has no effect on overall smoking or vaping prevalence. U.S. states that ban flavors miss out on tax revenues and Master Settlement Agreement money while the number of smokers stays the same and vapers buy their products in neighboring states. Prohibition by stealth, panelists agreed, stifles innovation and, given the discrimination against vape products compared to combustibles, may be potentially illegal in trade law terms.

Academic Freedom Under Threat

Misinformation about RRPs and the question of who can be trusted remains one of the biggest issues in tobacco harm reduction. While the trust in science has generally increased through Covid-19, countless flawed studies on less hazardous nicotine products continue to circulate, contributing to misperceptions among consumers. Google Scholar ranks studies according to popularity rather than quality, so even two years after e-cigarette or vaping use associated lung injury (EVALI), studies attributing the outbreak to nicotine vapes rather than illicit THC products still feature prominently in search results. But even research professionals are often interested only in the title, abstract and conclusion of a study and thus fail to detect flawed methodologies.

A recent example of misinformation is the claim by several emission studies that the aerosol of vape products is polluted with heavy metals. By providing a concise explanation of the ingredients of e-liquids and the complex chemical processes that take place in a device during vaping, Miroslaw Dworniczak, a Polish chemist and author, refuted this assumption, concluding that despite the presence of some potentially dangerous compounds, e-cigarettes were far less risky than regular cigarettes. Mexican physicist Roberto Sussman, who examined 12 studies on metals in e-cigarette emissions, found that all of them were methodologically flawed.

Having become ideological rather than evidence-based, the health debate about vaping is full of contradictions. Mark Tyndall, an infectious disease specialist from Canada, compared his experience working with HIV with the experience in vaping. It took 40 years for HIV to lose its association with fear, blame and stigma—issues that smokers and vapers are facing too. Medical treatment of AIDS was the greatest breakthrough—vaping, he claimed, could be a similarly efficient weapon to treat smoking.

Stigma is also present in the academic world, and it goes far beyond suspicion of tobacco-funded studies. Scientists detected “the ghost of Senator Joseph R. McCarthy,” the paranoid U.S. communist hunter of the 1950s, as they often confronted hostility from fellow academics and institutions. Experiences of suppressed academic freedom ranged from a lack of institutional support for THR research to “mobbing” and exclusion from faculties.

Here for Good, but …

So, is tobacco industry transformation a myth or a reality? Sharing her view from the corporate side, Flora Okereke, head of global regulatory insights and foresights at BAT, said that her company’s efforts to help smokers switch to less risky products—and therefore doing something for society—had given employees a sense of pride. Peter Stanbury, a political economist, evaluator and management consultant, pointed out that companies such as British Petroleum are also in the process of transformation, driven internally by people who realize that change is required and externally by regulation.

In advancing tobacco harm reduction, regional networks in THR consumer advocacy play a vital role. Nancy Loucas, founder and executive coordinator for the Coalition of Asia Pacific Tobacco Harm Reduction Advocates, related how her organization, faced with challenges such as government interests in tobacco growing and manufacturing, notably in China and Indonesia, and foreign philanthropist influence in the development of policy, achieved a paradigm shift in several countries by working with an expert advisory group.

Tobacco harm reduction, panelists agreed, is here to stay; consumers have a right to it. But accessibility of THR will remain a problem, and more restrictions are on the horizon.