Synthetic versus tobacco-derived nicotine

Cheryl K. Olson and Willie McKinney

Every year, the National Youth Tobacco Survey gathers data from U.S. middle school and high school students about all sorts of nicotine products and how they’re used. In 2021, for the first time the most popular brand of e-cigarette among underage users was a synthetic nicotine vape. Puff Bar was named “usual brand” by 26.1 percent of underage vapers, equaling the sum of the next three most popular brands: Vuse (10.8 percent), Smok (9.6 percent) and Juul (5.7 percent). While the summary of these latest findings in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report didn’t mention the word “synthetic,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration certainly took note.

One reason the FDA pricked up its ears is that synthetic nicotine, also known as nontobacco nicotine, lives in a legal gray area. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 expanded the FDA’s authority to regulate products “made or derived from tobacco” and created its Center for Tobacco Products.

This begs the question of whether the FDA has regulatory authority over synthetic nicotine. Predictably, manufacturers who use it in ENDS products claim that the FDA does not have that authority. If that’s true, those manufacturers can bypass the lengthy and expensive premarket tobacco product application process and go directly to market. But there are others, including attorneys who’ve studied this law, who believe that even if synthetic nicotine is technically not covered by the 2009 Tobacco Control Act, it meets the definition of a drug and is therefore subject to FDA regulation.

The substitution of synthetic nicotine for tobacco-derived nicotine has profound implications both for manufacturers and distributors of reduced-harm nicotine products. Is it a smart workaround, a temporary shelter or a costly dead end? Here are some of the key issues as well as ways to limit your risk as a company.

The Options

Over the past few months, many makers of flavored e-cigarette products have received marketing denial orders (MDOs) or fear receiving one. An MDO gives that manufacturer a limited number of choices: reapply for approval, get out of the business or sue the FDA for redress—or search for what it hopes is a legal loophole to the FDA’s regulatory authority. Hence, the move to synthetic nicotine as a too clever by half solution that carries with it underlying scientific, economic, legal and ethical issues.

Let’s start with an economic issue, which may trump all the others. Synthetic nicotine is expensive. In fact, it’s up to 10 times the cost of tobacco-derived nicotine, according to Kevin Burd, CEO of North America Nicotine. One reason is that tobacco-derived nicotine is made from leftover scraps from processing tobacco leaves—often literally the stuff left on the factory floor. Synthetic nicotine, most of which is manufactured in China, is created through a variety of proprietary chemical processes.

“As volumes increase, I can’t see the price of chemicals used in synthetic coming down to the price of waste tobacco, including dust,” said Burd. “It’s highly unlikely ever to be competitive.”

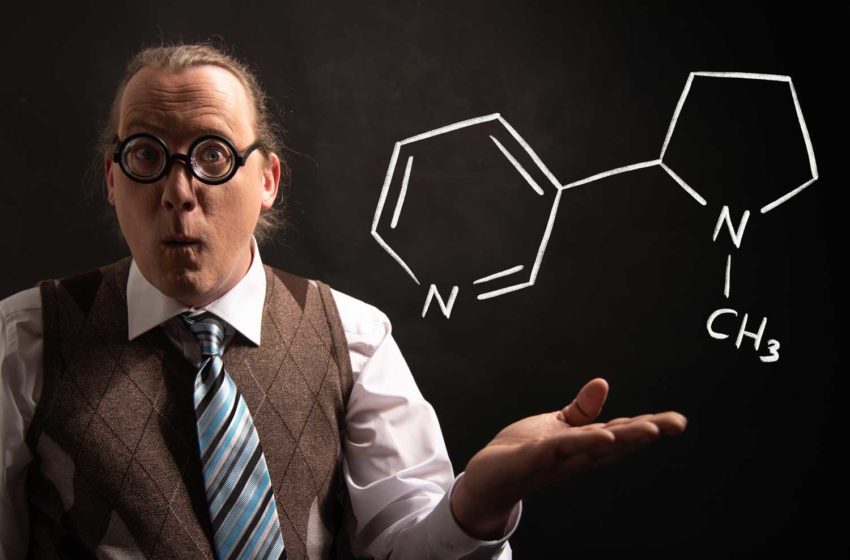

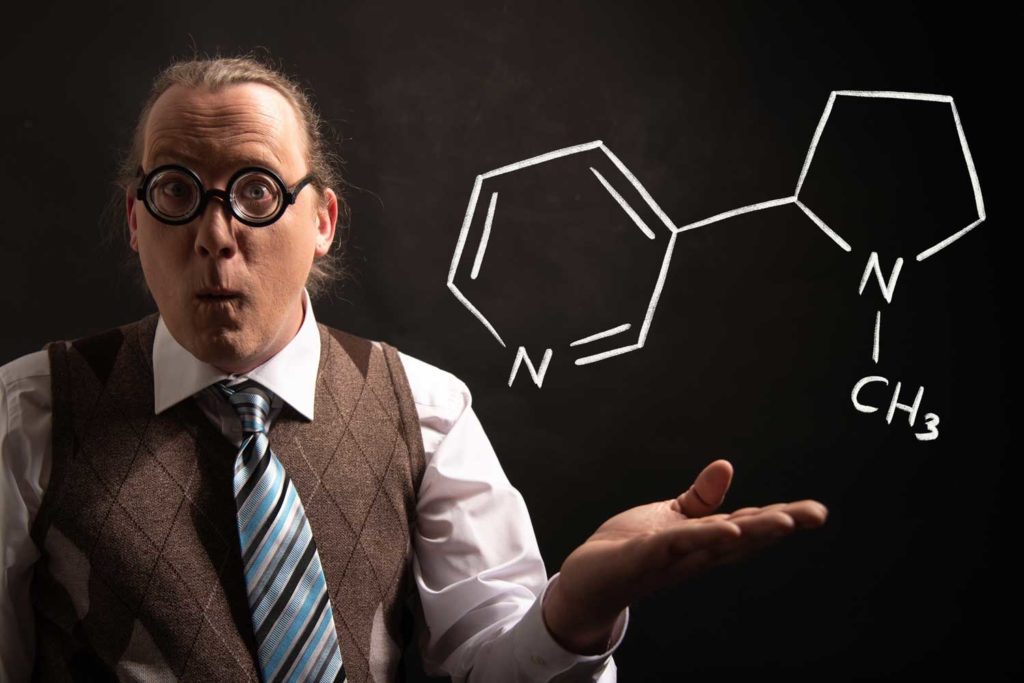

Both synthetic nicotine and tobacco-derived nicotine occur in two structural forms (enantiomers) known as R-nicotine and S-nicotine. More than 99 percent of the nicotine in tobacco is S-nicotine. In synthetic nicotine, that balance can be 50-50.

“Little is known about the pharmacological and metabolic effects of R-nicotine in humans,” says a 2021 article on the rise of synthetic nicotine in Tobacco Control (Jordt SE. Synthetic nicotine has arrived. Tobacco Control 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056626). In other words, synthetic product users could be unwitting research subjects. There are inexpensive tests for distinguishing between R- and S- forms of the chemical and ways of separating the R-isomer from the S-isomer. By comparison, telling the difference between synthetic S-nicotine and tobacco-derived S-nicotine can be quite costly.

This leads to an interesting paradox. We don’t know how much of the supposed synthetic nicotine is actually tobacco-derived nicotine. There’s a financial incentive for a manufacturer simply to replace the more expensive version with the cheaper chemical and mislabel it. In fact, on its website, Next Generation Labs warns prospective customers, “There are several companies from China claiming to have synthetic nicotine. NGL has tested several of these products and discovered they are made or derived from tobacco.”

Burd adds, “Quite likely, many [products that claim to be synthetic] are not really synthetic.”

Some companies are weighing the cost of regulatory compliance versus the higher manufacturing cost of using synthetic nicotine. That’s a false choice, for it underestimates the costs of unknown safety risks, product testing and emerging regulations. Simply marketing a new synthetic nicotine product without providing the necessary scientific and behavioral research data to the FDA will, at the very least, generate a warning letter.

Remember that the key reason for generating research data on a new product is to explore whether it will harm people. The FDA uses the term APPH (appropriate for the protection of public health). Not doing so puts your business at risk not only from regulatory actions but from civil litigation if someone gets hurt.

A regulatory update by FDA Center for Tobacco Products Director Mitch Zeller at an Oct. 27 Food and Drug Law Institute conference addressed the challenge posed by synthetic nicotine. Zeller’s slide deck makes clear his belief that e-liquids that do not contain tobacco-derived substances “may still be components or parts of tobacco products and, therefore, subject to FDA’s tobacco control authorities.” It also states that the FDA is “in discussions with Congress about a potential legislative fix.”

The Wild West

Burd expressed concern that synthetic nicotine, and the regulatory uncertainty driving its use, have put the vaping industry “back to the Wild West.” Even the pure S synthetic may contain residues from the unknown solvents that some new manufacturers use. Burd recommends that manufacturers who use synthetic nicotine “test their incoming material (emphasizing impurities and solvents), audit the supplier, do a toxicology review for product safety and be sure to use S-nicotine only.”

That type of analysis is impractical for end users, of course.

Finally, there’s the issue of whether a company is a “bad actor” that focuses on short-term financial profits at the expense of both public health and the lives of their customers. The FDA runs the risk of encouraging such unethical behaviors if it broadly bans products from those companies making sincere efforts to reduce the harm done to smokers of combustible cigarettes while ignoring companies that look for legal loopholes.

A Marketing Throwback?

The issue of synthetic nicotine regulation is likely to be resolved fairly soon. One reason is that the attractiveness of e-cigarettes to youth is rightfully a major concern of the FDA. Marketing materials for synthetic nicotine products have the tone of advertising done by an earlier iteration of Big Tobacco when it claimed that paper filters, toasting and other irrelevant variables reduced cigarettes’ negative health effects.

- American Tobacco Company (1930): “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating. Toasting removes dangerous irritants.”

- Liggett & Myers (1931): “Chesterfield Cigarettes are just as pure as the water you drink.”

- Brown and Williamson (1949): “Viceroys filter the smoke. As your dentist, I’d recommend Viceroys.”

- Puff Bar (2021): “Our nicotine products are crafted from a patented manufacturing process, not from tobacco. The result? A virtually tasteless, odorless nicotine without the residual impurities of tobacco-derived nicotine.”

- Next Generation Labs (2021): “TFN Nicotine is not derived from tobacco leaf, stem, reconstituted sheet, expanded or postproduction waste dust. The nicotine is made using a patented manufacturing process that begins with a natural starter material and progressively builds around the molecules of that material to create a pure synthetic nicotine.”

These claims (from company websites) about differences between synthetic and tobacco-derived nicotine misleadingly hint at safety without providing real data. They skirt the important scientific issues and focus on emotionally resonant phrases like “begins with a natural starter material,” “without the residual impurities” and “create a pure synthetic nicotine.”

Adolescents in particular may make the false inferential leap that synthetic nicotine somehow carries less risk or is less addictive than tobacco-derived nicotine, according to new research from Rutgers University and the National Institutes of Health. This, in turn, may lead nonsmoking, nonvaping teens to use the products often enough to become addicted. The risk of any new product to children is a tried-and-true political plank, so it’s likely to gain the attention of members of Congress, who could pass a law declaring all forms of nicotine to be under the purview of the FDA. —WMK and CKO