It is time to confront the fundamental confusion about the public health aims for tobacco and nicotine policy.

By Clive Bates

In 2013, the journal Tobacco Control published a supplement, “The Tobacco Endgame,” setting out various ways in which various experts thought a tobacco-free society could be attained. Ideas included annually increasing age limits, a cap and trade system, outright prohibition, taking control of the industry and making it put itself out of business, and removing most of the nicotine from cigarettes. In the intervening seven years, most of these ideas have not progressed at all. And rightly so, as I argued in a detailed critique, these policies are mostly impractical or excessively coercive and would fail if tried. The only one that attracted any real interest was the idea of lowering nicotine concentrations in cigarettes to make the product subaddictive (i.e., to eliminate the main reason people smoke). But even this de facto prohibition has not fared well. After backing the idea in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) dropped the reduced nicotine rule from its regulatory plan in 2019. The most senior researchers engaged in the idea recently acknowledged that its viability would depend on the availability of credible safer alternatives to smoking.

So, all this begs the question, where is the endgame now? Or maybe the more interesting prior question is: endgame for what? What will end and what, if anything, will continue? Does the endgame mean the end of tobacco and nicotine use? Or is the endgame, as I believe, the final stages of a transition—a shift from an unsustainable to a sustainable nicotine market?

At the heart of this question is a fundamental confusion about the public health aims for tobacco and nicotine policy. This dispute is rarely surfaced and never resolved but confronting it has now become unavoidable. At least five objectives can be identified in tobacco control: (1) reducing disease and premature death; (2) eliminating smoking and smoke exposure; (3) eliminating tobacco; (4) destroying the tobacco industry; and (5) achieving the nicotine-free society or “ending nicotine addiction.” When the consumer nicotine market was supplied almost exclusively by cigarettes, it was possible for activists to say, “all of the above.” Activists could get away without having to declare or even recognize their underlying aims or to face the trade-offs and tensions between them.

No longer.

Even in the 1990s, splits in tobacco control were already emerging over snus, an obscure Scandinavian oral tobacco product. The faction interested in reducing disease was intrigued by Sweden’s abnormally low smoking rate. Toxicology and epidemiology suggested that substantially lower rates of disease in Swedish men were due to use of snus as an alternative to smoking. For that group, the harm reduction potential of snus had great potential. However, the faction interested in the end of tobacco saw the European Union’s ban on snus (other than in Sweden) as a win and incremental progress toward their goal of the tobacco-free society. Thirty years later, snus remains banned in the European Union despite undeniable evidence that snus reduces smoking and by doing so, reduces individual and population harm. This willingness to forego major public health benefits should tell us something fundamental: The dominant tobacco control faction is engaged in a war-on-drugs mission and not, as often assumed, a public health crusade. It is trying to forge a path toward a nicotine-free society with little concern for the collateral damage inflicted to health on the way to meeting its goal.

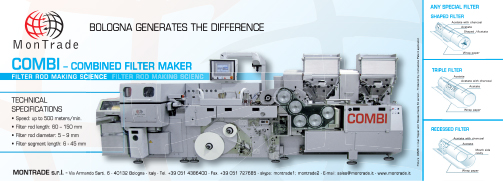

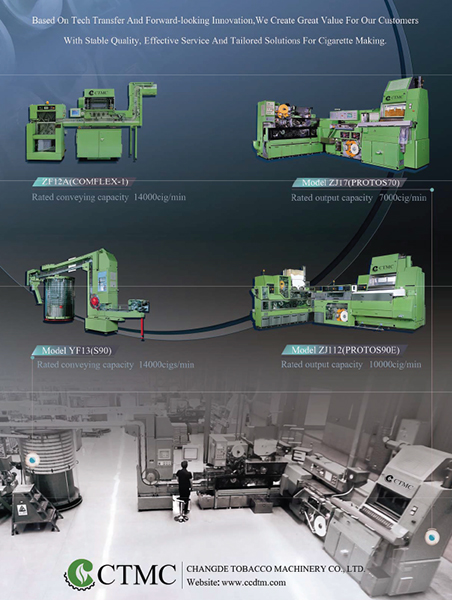

However, the rise of vapor and heated-tobacco products in the last 10 years means this is no longer a localized conflict. The harm reduction “proof of concept” of snus can now be generalized to an experience much closer to smoking in every respect other than harm to health. Add in the recent developments in oral nicotine pouches, which will make snus-like products more acceptable to a much larger population, and the diverse portfolio of smoke-free alternatives to smoking is starting to look quite formidable. The products available to nicotine users have changed beyond recognition in the last 10 years. If we project forward through another 10 years or 20 years of innovation in these new categories, imagine how the market could look in 2030 or 2040.

This is the opening phase of the technology disruption now roiling the industry. But it is also disrupting the tobacco control community by surfacing the tensions between its objectives. In particular, we are seeing the goal of the “nicotine-free society” coming to the fore, with an increasing stress on nicotine and the inclusion of goals to end nicotine use or “nicotine addiction” where there was previously an aim to pursue the end of smoking or to prevent disease.

Even many public health supporters of “tobacco harm reduction” see the smoke-free products as an expedient and effective way of helping to stop smoking—a sort of pimped-up nicotine-replacement therapy. And that is a good argument, as far as it goes. But it doesn’t really settle the question of our collective attitude to nicotine over the longer term.

To look ahead, let’s consider the situation in Norway where daily smoking among 16-year-old to 24-year-old women has fallen from 15 percent to only 1 percent in just 10 years, according to 2019 data from Statistics Norway. Have they stopped using nicotine? No, they have been using snus from the outset. By 2019, daily snus use was at 14 percent in this group. That group is now using nicotine without ever starting to smoke, and they probably never will. Harm reduction supporters argue that this is “a win” for public health because without the use of snus, many of these young women would otherwise be smoking. But how will that argument look in 10 years or 20 years when cigarette smoking may be well on the way to obsolescence?

Here we need to confront the deeper question about nicotine that goes beyond harm reduction in which the cigarette is the reference point for harm. The concept of harm reduction feels unsatisfactory in this context—what if no one uses a harmful product to start with? If there is going to be a long-term market for nicotine, the question becomes how to regulate a recreational nicotine market based on consumer-appealing products with risks that are within our normal appetites for risk? I believe the product portfolio is now evolving toward how it could look over the longer term—smokeless and electrically heated tobacco and nicotine products. I don’t expect the combustible products to disappear but to become a niche interest—like vinyl records in a world dominated by digital music streaming.

For some in tobacco control, this is a nightmare vision. This is not the nicotine-free society that has been their ultimate endgame. But if the harms are not particularly large and the drug is popular, why should governments stop people using it? Drug use is pervasive in human society and throughout history, perhaps started by our hominid ancestors millions of years ago. Nicotine, a relative newcomer, was domesticated between 6,000 years and 8,000 years ago. To say that a drug should be legal and available in relatively safe form is not to endorse its use or somehow to recommend it but to acknowledge that some people may wish to use it, and there isn’t a good reason to stop them by force of law. That idea has both philosophical and practical underpinnings. The philosophical foundation recognizes adult autonomy and the right to indulge in risky behaviors that do not harm others. The practical experience of prohibitions is that they do not work (a new supply chain is established by criminals) and cause serious harms to the individual and to wider society.

Prohibition does not even protect adolescents. Despite federal prohibition, past-30-day use of cannabis among U.S. 12th graders has been over 20 percent for at least a decade. The recent U.S. lung injury outbreak that hospitalized 2,800 and killed 689 was largely a consequence of reckless criminal behavior in the illicit supply of cannabis (THC) vapor products.

As a drug, nicotine is relatively innocuous—it doesn’t cause serious disease, intoxication, overdose, violence, road accidents, sexual vulnerability, incapacitation or family breakdown. Perversely, this relative safety becomes a serious tactical problem for the war-on-drugs tendency in tobacco control. If the prospects of cancer, lung disease and heart disease are greatly diminished, why should people fear nicotine? It is even possible that more people will take up nicotine if the consequences of using it are much less dreadful—that would be the economist’s assumption. Harm (from smoking) is the most persuasive reason not to use nicotine, and that reason is going up in a puff of vapor. In a weirdly inverted way, the greatest threat to the nicotine-free society is the availability of relatively safe nicotine products. I think that explains why so much strenuous, even desperate, effort is going into finding serious harms in smoke-free products though, beyond reasonable doubt, there are none.

The theme of this year’s online GTNF 2020 is “Sustainable change through innovation and regulation.” It will be a great opportunity to discuss the future of nicotine in greater depth.