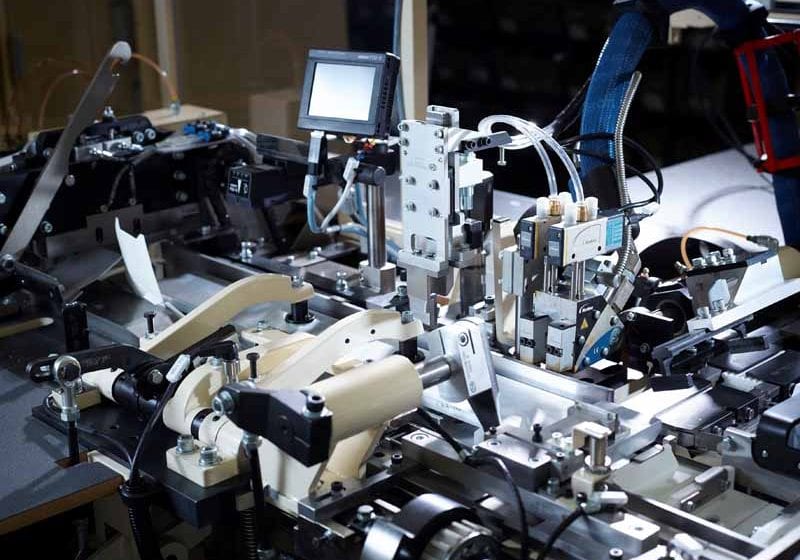

Suppliers of equipment rebuilding services have found different strategies to cope with the challenges of a changing tobacco industry.

By Stefanie Rossel

As the tobacco industry finds itself in a period of transition amid globally shrinking cigarette sales volumes and increasing product regulation, the market for reconditioned tobacco making and packing equipment is also altering.

Breathing new life into older machinery has always been considered to be a win-win situation for customers as well as for equipment providers: Tobacco companies benefited from having their reliable workhorses revamped at manageable costs instead of acquiring significantly more expensive new equipment, while rebuilding and overhauling services were a viable business for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and non-OEMs alike. But to what extent is this still the case? The suppliers of refurbished tobacco equipment Tobacco Reporter spoke with provided largely differing views.

Christian Wiethuechter, managing director of Hauni Richmond, the U.S. subsidiary of German tobacco equipment manufacturer Hauni, says his company recently had to expand its portfolio in the rebuilding sector. “Based on the close cooperation with our global customers, we have experienced that it is not the OEM’s [need] but the client’s need that determines the products and services we offer,” he says. “Customer demands have driven us to expand our offerings for our large installed machine base. Today we can provide tailor-made maintenance programs on site, different levels of machine modernization and partial overhaul, as well as full rebuild ‘as new’—we let our customers decide what exactly fits best their specific demands.”

Wiethuechter says the business remains generally stable and is driven by the existing machines portfolio with a trend toward electrical solutions. “As we jointly develop customized solutions with our customers to optimize the installed machine base, we can see an opportunity for a positive development in this sector of our business in the years to come, independently of the cigarette volume trend.”

Other players are less upbeat. “It depends how you define ‘rebuilding,’” says Rik Kamps, sales manager of make pack services at ITM in the Netherlands. “If we talk about a complete rebuild ‘as new,’ then, yes, this is less attractive. Nowadays all kind of manufacturers are interested in machine lifetime extension, meaning partial rebuilds. Our customers are more and more looking for cost-effective solutions. Fully rebuilt machinery does not always meet that requirement. We believe that many machines are so well-built that a full mechanical rebuild isn’t always the financially right solution.”

He continues: “ITM has a long track record in rebuilding machinery, and therefore we know exactly which areas needs to be improved—and to what extent—to get the best value for money. Our goal is to refurbish or rebuild machines in a way that they are easily serviceable, with the highest possible overall equipment effectiveness and the best possible return on investment. We believe this is also what our customers are looking for.”

Adriano Fanzellu, regional sales manager at Molins Tobacco Machinery, observes that, in the era of computer-integrated manufacturing and the internet, the strongest argument for rebuilds is about to lose its persuasive power: “As new inverter-driven systems on new machinery replace expensive complex mechanical gearboxes, the cost difference between rebuilding and new equipment becomes greatly reduced, and customers are now more than ever looking at new equipment rather than full rebuilds, with buyback of old equipment adding an additional option.”

Following contracting global cigarette sales, however, he says that customers are looking for more cost-effective methods of extending their machinery lifespan. “We see an increase in on-site machine overhauls.”

Molins still offers a full rebuild service, which is greatly dependent on the machinery requirement and customer location. “The majority of rebuilding is done at our Brazilian location, but we have and can also offer this service at our location in Pilsen dependent on the actual requirement and equipment type.” At its Brazilian subsidiary, the company focuses on rebuilding tobacco processing equipment, which it sells to the Latin American and Asian markets, where Molins has identified the greatest demand for such services.

Quick solutions

The business of machinery rebuilding has declined measurably in recent years, according to Norbert Schulz-Nemak, sales manager at German tobacco machinery supplier TMQS, which focuses mainly on secondary making equipment. “The ‘classic’ rebuild, where machines are fully overhauled at the supplier’s premises or an overhauling center and then sent back to the customer, is not asked for that much anymore as far as we are concerned,” he says. “As far as we can tell, this has two main reasons: The time for which the machine is out of production is too long with current production pressure for most factories, and/or the price does not fit in compared to alternatives.” Schulz-Nemak says that, in his company’s field of business, the untapped potential for rebuilding is somewhat limited. “I cannot foresee what it might become like in the midterm, but given the way that machines are heavily used for production at the moment, chances are that something—i.e., some rebuilding—needs to happen to some of them once time and production schedules allow,” he says.

His company, too, offers different grades of makeovers. Apart from a full mechanical and electrical rebuild, the TMQS portfolio comprises efficiency kits. These are tailor-made packages of parts, subassemblies and services that guarantee 85 percent production efficiency, according to Schulz-Nemak. In addition, the company provides e-kits to replace obsolete electronics. In contrast to a full rebuild, the packages can be installed on site after a thorough inspection, thus saving time.

As far as profitability for equipment manufacturers to breathe new life into older machinery is concerned, machinery supplier Aiger, which has its headquarters in Switzerland, finds itself at the other, not so optimistic end of the scale.

Aiger Group has mostly withdrawn from the tobacco machinery refurbishing business. Today, only 5 percent of Aiger’s turnover comes from this activity. Instead, the company concentrates on the development of new machinery. “The tobacco industry and machinery builders should focus on innovation and new product development to battle the ever-increasing pressure from governments and regulators,” says Yanko Yanchev, Aiger’s business development director. “We need to change the game on advertising, harm and health risks, etc., and this will happen only through radical innovation in the whole industry. Therefore, I see no future for the rebuilding of current technologies.”

Finding the right niche

Other suppliers, by contrast, have found niches where their rebuilding services are in high demand. For Ascent Techno Management Services (ATMS) of India, which traditionally deals with smaller independent cigarette manufacturers, it is partly a geographic niche. ATMS founder and owner Harsh Rai sees potential in Africa, Southeast Asia, parts of Latin America and the Middle East.

Nevertheless, says Rai, the sector is no longer as it used to be. One factor is Asian equipment manufacturers offering brand-new, fully compliant and up-to-date low- and mid-speed cigarette making machinery at a price that is only slightly higher than the cost of a rebuild. “The competition from Asian equipment manufacturers has eaten into [the sales of] the old rebuilding companies,” Rai says. At the same time, the slowing growth of cigarette sales had reduced demand for machinery. “It’s a double pincer,” says Rai.

His observations are in line with those of Fanzellu, who has seen rebuilders of Molins machines disappearing, leaving customers with rebuilt machines with “special part numbers” and no spares support. Such customers are now approaching Molins to bring their machines back to OEM standard, complete with documentation.

While the market for reconditioned machinery has become difficult with regard to standard formats and products, Reto Iten, of HSI Tobacco Service & Spare Parts, has found the rebuilding of “as new” machinery, with state-of-the-art technology and electronics, for special or lower-quantity products to be a promising niche.

HSI concentrates on refurbishing maker groups for cigarillos and special formats. It also offers tailor-made machines for special packaging projects. Rebuilds account for 80 percent of HSI’s business. Iten’s customers are small- to medium-sized factories all over the world. “Lower-volume manufacturers, special products [companies] and contract manufacturers are often going to have the machines rebuilt rather than [buying them] new,” says Iten. “For their product range, a high-speed machine does simply not make sense and is too expensive.”

Declining markets also mean that cigarette factories are looking for cost savings. “So they invest in efficiency, keep their present machines and may even upgrade them—and some go for fancy new packs,” says Iten.

HSI has also benefited from new regulations, such as the European Union’s revised Tobacco Products Directive, which entered into force May 20 and has required some packaging format revisions. And of course, all tobacco companies are interested in better-running equipment.

Opportunities through relocation

One of the main trends in machinery rebuilding, suppliers agree, is obsolescence controls. “Electrical upgrades are the No. 1 requirement,” confirms Fanzellu. “We have an extensive range of upgrade kits, which customers select mainly to achieve high production efficiencies.”

Kamps observes that the still-operational but obsolescent systems are gradually becoming more difficult and expensive to service, while the risk for downtime increases. “Obsolete controls will sooner or later be a showstopper,” he predicts.

Meanwhile, the long-standing quest for cost reductions and efficiency increases continues. In recent years, the leading cigarette manufactures have undertaken actions to optimize their manufacturing footprints. To remain competitive in a declining market, they have been closing factories and consolidating production.

As a consequence of these moves, a considerable amount of relatively new equipment has been set free. Many such machines have been reinstalled at other manufacturing sites. While this strategy more or less stifles investment in new machinery, it also means demand for services to dismantle, move and reassemble equipment. For tobacco equipment suppliers, these processes have opened up new business opportunities.

“Relocations have definitely increased, and here again we have the capacity, know-how and experience to offer services—from pure relocation plus customer-specific solutions for maintenance, partial overhaul, obsolescence kits and format changes, to tailor-made solutions fitting to customer needs,” explains Andreas Panz, executive vice president of rebuild at Hauni.

Benefiting from its broad knowledge about makers, packers and buffer systems, ITM has done several relocation projects, according to Kamps. “This allows the customer to work with a single service supplier for complete make-pack lines.”

Yanchev says that while the relocation projects Aiger has worked on have not significantly increased the firm’s business, they presented an opportunity to reconnect with old customers. “It has also opened some new doors for us,” he says. “Moving to Eastern Europe has made our support easier as we are strategically located in the region, and I believe it has allowed us to provide even better service and ease of operation for our customers.”