Andrew Hopkins, BAT’s head of manufacturing, talks about the challenge of building a globally integrated supply chain and the importance of flexibility in an increasingly competitive market.

By George Gay

Facing fiercer competition and stricter regulations, cigarette makers are increasingly demanding of their equipment suppliers. Tobacco machinery must be fast, efficient and versatile—and of course reasonably priced. During the TABEXPO Prague Congress, Andrew Hopkins, British American Tobacco’s head of manufacturing, will discuss the criteria that matter to him and his colleagues when it comes to tobacco manufacturing lines. European Editor George Gay spoke with Hopkins in London, and he offered a preview of the issues likely to be raised during the machinery sessions at the Prague Congress.

Speaking with Andrew Hopkins in December was something of a revelation. I had gone to Globe House, British American Tobacco’s (BAT) London head office on the afternoon of Dec. 23 having spent the morning reading the Internet’s latest batch of anti-tobacco news, ingesting on the train a dire lunch washed down with the even worse economic predictions of my newspaper, and then enduring a brisk walk along the Thames Embankment in typical English weather. I guess I was prepared for something of a gloomy interview, but Hopkins was keen to talk to me about innovation and opportunities.

He reminded me of how BAT had announced to the City some time ago that it would make savings of £800 million ($1.28 billion) during the following five years, and he explained that these savings were being made largely by constructing an increasingly consumer-driven, globally integrated supply chain. “By doing this, we think we will be better configured to deliver innovation quickly to market; so building a truly integrated global supply chain is more about growth than productivity,” he said. “And we are very excited about that. We think that is a big opportunity for the group.”

One of Hopkins’ remits in his capacity as head of manufacturing for the group, which takes in people, processes and technology, is to integrate, at a global level, manufacturing with the other supply chain functions, and with the commercial side of the business. Although a lot of work has been done already in optimizing local and regional operations, it is clearly a daunting task integrating manufacturing operations that produce, as well as other tobacco products, about 650 billion cigarettes a year in 45 cigarette factories around the world.

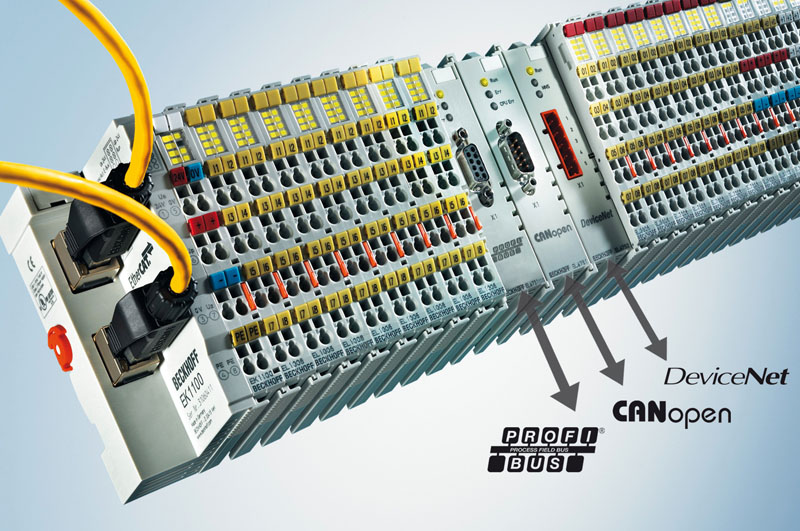

In part, Hopkins gets to grips with these problems of scale by imagining the factories as a single, “virtual” factory operating on many sites, and by dint of BAT’s centralized system of acquisition of equipment and services, which, he says, has “enormous” advantages. Group procurement of machinery via the central manufacturing team allows the leveraging of scale, the driving of standardization, the mobilizing of best practices and the development of strategies with OEM suppliers.

At the moment, BAT is looking at a number of projects linked to the global provision of service and spares support, and Hopkins told me he was interested in examining the possibility of developing a business model under which OEMs would do the maintenance on specific, mainly newer-generation equipment owned by BAT. But he added the proviso that such arrangements would be contingent on their delivering to BAT some value, which wouldn’t necessarily be directly financial.

At this point, I couldn’t help asking whether such a development could lead to BAT becoming a brand owner for which its current OEMs made cigarettes. But Hopkins gave this idea short shrift, pointing out that BAT’s manufacturing capability provided the potential for its gaining a competitive advantage. “We think that the OEMs are very good at making equipment and that we’re very good at manufacturing cigarettes; it’s as simple as that,” he said.

But in one way, simple it’s not, because BAT has a big portfolio of brands and products. Their growth strategy is based on four global drive brands (Kent, Dunhill, Lucky Strike and Pall Mall), which will drive more focus long term; however, since the company believes in “driving growth through innovation” additional complexity is expected to be created. Indeed, it is intent on driving innovation faster and further in the future.

BAT, Hopkins said, had more brands and more SKUs than did its competitors, and this meant more manufacturing complexity, an average batch size that was estimated to be smaller than those of its competitors, and, therefore, the need for more machine changeovers.

Given this manufacturing environment, BAT tends to look more to medium-speed makers and packers than to the very highest speed equipment. The group’s business was complex, Hopkins said, and it found that flexibility and responsiveness in the supply chain—because manufacturing was part of the supply chain—were more important than all-out, ultra high speed.

Speed, as far as Hopkins is concerned, is more crucial in respect of speed to market. He is passionate about innovation, though adamant that innovations have to be right; they have to be delivered to the market on time, on specification and at a cost commensurate with the risk involved. And the products of that innovation have to be produced in such a way that they can be reproduced in other locations should that become necessary.

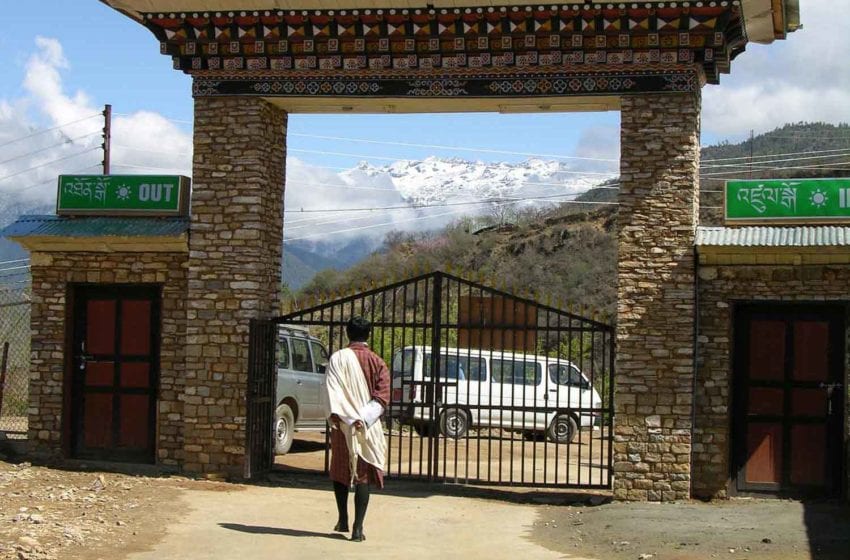

An honors graduate in mechanical engineering, Hopkins started work with BAT’s corporate engineering department in Southampton in 1991, where one of his first projects saw him involved in testing high-speed cigarette makers. Since then, and prior to taking up his current job, his career has seen him appointed to increasingly senior positions in Hungary, Uzbekistan, Belgium, Zimbabwe, the U.K. (again) and Russia.

I was keen to find out what had been the highlight of his career to date, but he was not to be drawn, preferring to speak of all of his appointments as hugely rewarding in respect of their business challenges and life-changing in respect of the cultural journeys they provided. The highlights just keep coming, he told me.

But Russia must come close. When Hopkins arrived in the country, BAT had a 90-billion-cigarette capacity, which, under his leadership, was expanded to 120 billion in three factories. Hopkins and his team created an eastern Europe supply chain and integrated the Uzbek and Ukrainian factories into an eastern Europe cluster.

“We drove the business growth through innovation in Russia harder than anywhere else in BAT,” he said. “ What it [the Russian market] taught me was that if we are going to innovate, we have to be first into the market and we have to be quick; so we need technology platforms that are going to work and that are flexible—that can handle a wide range of applications,” said Hopkins.

Flexibility is a word commonly used by all of the major cigarette producers, but it is particularly true at BAT with its emphasis on limited-edition packs and new formats. So, I asked where we were on the journey toward true equipment flexibility.

Generally, what had improved was the ability to change a pack, said Hopkins. With a king-size pack, it was a lot easier than previously to go from a square edge to a beveled edge or a round corner, to the point where this was regarded as a basic capability.

But Hopkins said he was looking for more flexibility. “That’s a challenge for us and we’re talking to a number of OEMs about it,” he said. “And they’ve got some concepts and thoughts about how we could gain more flexibility without losing massive amounts of productivity. So that’s something we’re interested in.”

With talk of the future, I took the opportunity to ask Hopkins what a state-of-the-art cigarette factory might look like 10 years from now.

“I think in general there’ll be more automation,” he said. “I think there’ll be a lot more on-line, real-time quality checking, and more real-time, on-time information for operators at machine level—with more empowerment. For example, they might have direct connection to the consumer complaints database so that they can see what quality aspects they need to be looking for when they’re producing a batch.

“I think we’ll pay even more attention to product integrity and repeatable quality; and there’ll be more of a move to a zero-defects environment.

“And shop floor systems will have to be far better adapted to providing a lot more variety as more and more restrictions on advertising take place. We’ve got to adapt the business. Consumers like personalization; they like variation; they like new things. You see that in other products; so why not in cigarettes?

“As I’ve said: innovation is what drives growth for BAT.”

Andrew Hopkins will be speaking at TABEXPO about flexibility and other manufacturing-related topics. To sign up for the Congress, please visit www.tabexpo.org.