The level of government control over the tobacco market varies across Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, it is relatively strict while in some other countries, such as Kyrgyzstan, it leaves a lot to be desired.

In 2021, the Kazakh government estimated that the share of illegal trade on the domestic market was close to 1.6 percent. Market players have doubts about whether this figure is correct, however. JTI Kazakhstan, for instance, put this rate at 3 percent to 5 percent, which is in line with the estimation of the Association of Trade Enterprises. Moreover, the steady rise in excise tariffs will likely drive this figure up by 1 percent to 2 percent per year, according to Alyona Stepanishina, external communication manager of JTI Kazakhstan.

Over the past two years, the share of illegal tobacco products in Uzbekistan jumped from 4 percent to 15 percent, Komil Abdurakhmonov, a spokesperson for the Agency for Regulation of Alcohol and Tobacco Market, estimated.

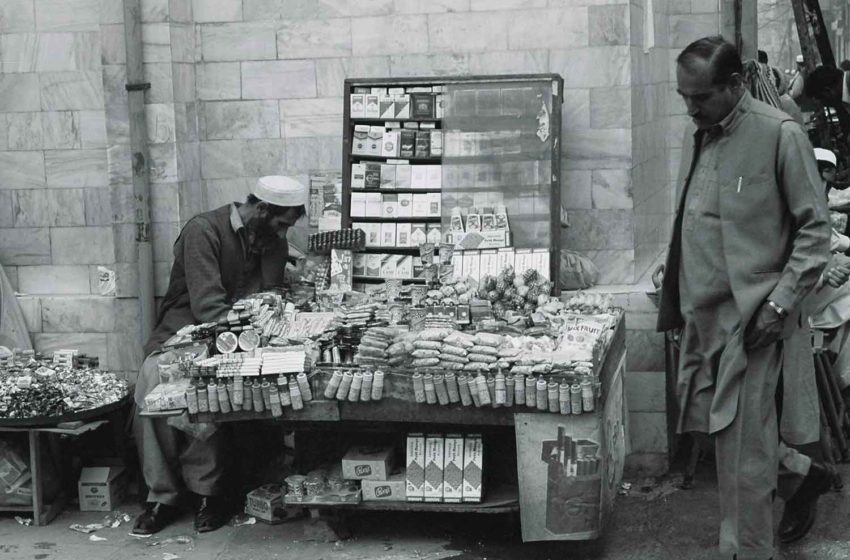

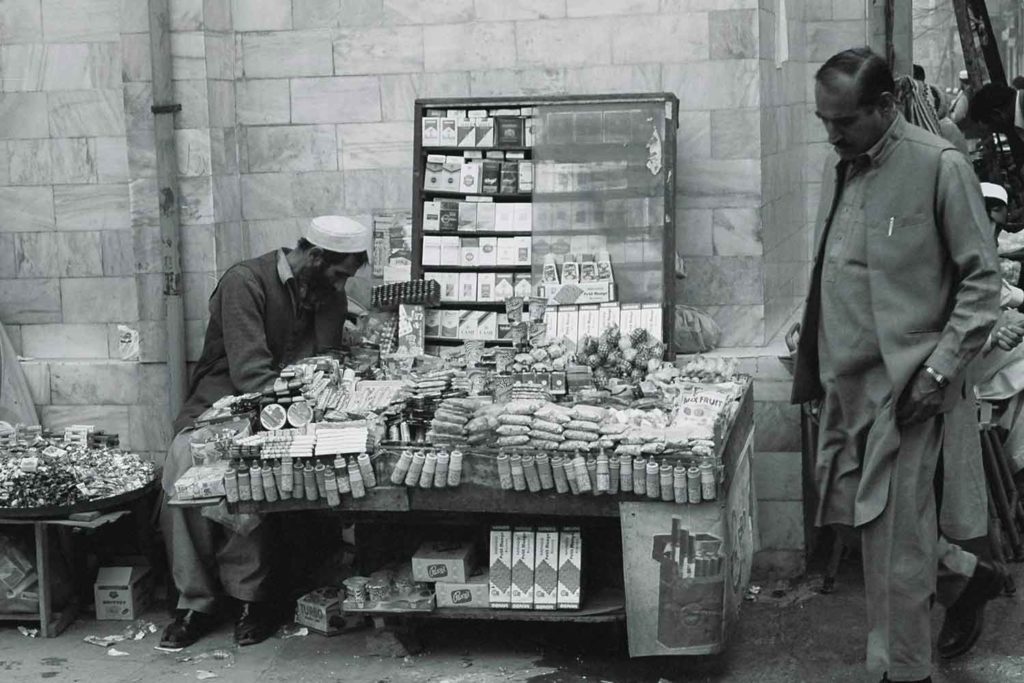

The lion’s share of illegal tobacco in the market comes from smuggling and flows into the country through the southern regions, Abdurakhmonov claimed. Commonly smuggled brands include Milano from the United Arab Emirates and KT&G’s Esse, he said. The cigarettes are first delivered to Kirgizstan and Tajikistan to be further smuggled to Uzbekistan.

“A series of recent studies showed that in all stores and the markets, we have Milano cigarettes, coming from Dubai. Their price is much lower than that of the local brands, and many consumers smoke them because of the price,” Abdurakhmonov said, adding that there are also substantial concerns over the quality of these products. “Simply checking information on the label, we can see that the level of nicotine content in these cigarettes by several times exceeds the allowed levels,” he added.

Ulugbek Kasimov, a spokesperson for the Uzbekistan State Customs Committee, also blamed Kyrgyzstan for illegally exporting tobacco products to his country. He disclosed that a large part of the shipments goes through the porous southern border. In this case, the customs service is nearly powerless to pull the plug on smuggling.

This is not the first time Kyrgyzstan has been blamed for large-scale cigarette smuggling in the region. The country shares a common customs space with Kazakhstan within the Eurasia Economic Union and is believed to be reexporting cheap cigarettes to several neighboring countries. In 2019, consulting firm KPMG reported that nearly a third of cigarettes entering Kyrgyzstan are reexported to other parts of Central Asia and Russia, often through various smuggling channels.

Azamat Arapbaev, a member of the Kirgiz Parliament, said that a large share of illegal cigarettes entering the country come from the Middle East, Tajikistan and Serbia while some cigarettes make their way to the market from duty-free stores on the border. He estimated that these supplies have a big impact on the domestic cigarette market, where sales are close to 3.2 billion units per year.

A 2022 study conducted by the think tank IPSOS showed that the share of illegal cigarettes on the domestic market of Kirgizstan is close to 9.5 percent. Kamila Aikultlova, an analyst with IPSOS, estimated that the national budget lost between $6 million and $7 million from illegal trade on the domestic market. Meanwhile, in Tajikistan, illicit cigarettes accounted for a whopping 74.2 percent of retail sales in 2021, according to Nielsen.

The future of the Kazakhstan tobacco market is tightly linked with a proposal, published by the healthcare ministry in early 2023, to ban vapes. Alibek Kuantirov, the economy minister, backed the initiative, claiming that the Kazakhstan society favored this idea. He promised that tobacco-heating devices would not be banned. Still, Olga Krutova, an analyst with local publication MK, assumed that the restrictions in this field would give further impetus to the growth of the illegal tobacco market.