Climate change, war and a lingering pandemic exacerbate the typical challenges presented by leaf tobacco supply and demand.

By George Gay

I have a question. Given the environmental crisis the world faces, why are the tobacco industry’s operations dominated by flue-cured tobacco varieties rather than sun-cured varieties? I mean, why cut down trees and burn them as part of the flue-curing process when it is possible to rely on the energy freely and directly available from the sun to cure tobacco? It cannot be a quality thing because whereas, for example, sun-cured classical oriental tobaccos are sublimely aromatic, flue-cured Virginia tobaccos are unremarkable at best.

Another argument that cannot be made is that the industry was not aware of the deforestation it was causing by flue-curing tobacco and therefore hasn’t had time to switch from flue-cured to sun-cured tobaccos. The issue of tobacco-driven deforestation was being widely discussed in the early 1980s and probably before that. Of course, not all flue-curing relies on burning wood, but that which doesn’t, as far as I am aware, requires, directly or indirectly, burning fossil fuels.

So what is the answer to the question posed above? I think there are probably very many answers, none of them particularly convincing, so I believe that even now efforts should be made to switch production from flue-cured varieties to sun-cured and, perhaps, air-cured varieties. And maybe this will happen, partly because of the growing alignment of environmental and health activists and arguments.

A recent report by the World Health Organization and Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products (STOP), Talking trash: Behind the tobacco industry’s ‘green’ public relations, accuses the industry, mainly in the guise of the four major multinationals, of “greenwashing.” And though some of the report is lightweight and unconvincing, its uncomplicated messages are likely to register with a nonindustry audience. “Tobacco growing and curing are also both direct causes of deforestation,” the report says in part.

In addition, according to Natalia Pujalte writing in May in The Parliament Magazine, the EU presented in November a proposal for new regulations that would allow “only deforestation-free and legal products” to be sold on the EU market. Tobacco wasn’t mentioned in Pujalte’s piece, but with the regulations still under consideration and the EU’s aversion to all things tobacco, it is unlikely the industry will slip through the net.

Pressing Challenges

I suspect that 99 percent of those working in the tobacco industry will disagree with my suggestion and come up with all sorts of reasons why sun-cured and air-cured tobaccos cannot be used as the main ingredients in cigarettes, at least in part because they have other things on their minds. According to a number of respondents to a Tobacco Reporter questionnaire, the leaf industry is suffering from the effects of everything from climate change to the war in Ukraine and long Covid.

Although Jose Maria Costa of NewCo said leaf tobacco demand from a wide range of customers was holding up well, he positioned a range of industry problems within that affecting just about every business and individual globally. The world had been through 15 difficult years since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, he said. And more recently, the war in Ukraine had been launched before economies around the world had a chance to recover from the impact of the Covid pandemic. The developed world was currently facing levels of inflation not seen in decades, so the entire supply chain was suffering cost increases that were very difficult to offset. Logistical challenges that had been evident for a year were adding to the problems, with prices for a container quadrupling for certain routes. At the same time, there were smaller-than-desirable tobacco crops in key markets such as Brazil, and prices were going through the roof in all markets.

And whereas the tobacco industry had been through a lot of changes and cycles over the years, things were different now, Costa said, implying, I think, that there were now more, worse problems that were proving harder to overcome. The world needed a period of stability, and the tobacco industry did too, throughout its supply chain, he said.

Craving Consistency

Meanwhile, Christian Adi Njoto Njoo, the president of Mangli Djaya Raya, which for more than 60 years has produced, processed and traded tobacco from its base in Indonesia, told Tobacco Reporter that his current main concerns are focused on how to ensure production is sustainable in the face of anomalous weather patterns and how to address market inconsistencies. Addressing the challenges caused by climate change would need an elaborate plan devised and supported by a broad range of stakeholders, including governments, and would be a long-term project, he said. And in the meantime, recent prolonged rainy seasons in Indonesia were predicted by the Indonesian Agency for Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysics to continue through at least this year and next, which could mean shorter crops and prices rising to previously unheard of levels.

On the other hand, market inconsistencies could be improved in the short term, Njoto said. They were caused by a lack of central planning that allowed a vicious season-by-season cycle of production boom and bust to develop as growers, who were not fully informed, reacted to the prices paid in the previous season, not necessarily to the needs of the current season. Some market inconsistencies, he added, could be improved through government regulation and by better and consistent planning by medium to large corporations when deciding on their purchasing, production and price indications for future seasons.

One indirect result of the boom-and-bust cycle was volatility in the stocks and prices of fertilizers and crop protection agents, followed inevitably by higher production costs and pressure for tobacco price rises. The scarcity of fertilizers in recent times had seen their prices increase hugely to the point where the government was currently trying to control the sale of fertilizer on the domestic market and to limit and even ban its export.

On the Bright Side

The Tobacco Reporter questionnaire asked, basically, what is currently positive about the leaf tobacco industry, what is negative and what can be done to improve things.

Njoto identified unhelpful regulations as being a problem for the industry, though he recognized that regulations were necessary in respect of protecting certain industry stakeholders, especially farmers and workers, and also the environment. In fact, he accepted that, in Indonesia, regulations were less strict and made more sense business-wise than those in some other countries and regions. It was also helpful that government-owned tobacco research facilities, laboratories and other institutions had been steadily improved in recent years through increased budget allocations drawn from various tobacco industry-related tax revenues. At the same time, government and private extension services, including the gradual implementation of sustainable tobacco programs required by the major multinationals, were aiding tobacco farmers, workers and other industry stakeholders.

However, he said, it was concerning that “international regulations” were starting to be introduced, and introduced without enough consultation, which meant some were poorly received and adapted and therefore hindered the industry’s stability and development. This situation needed to be improved by ensuring a balance was struck between the health and economic interests of all stakeholders.

Interestingly, ITC, India’s dominant tobacco manufacturer that has been closely linked to the success of the country’s flue-cured tobacco industry, mentioned no problems in its response to the questionnaire, preferring to concentrate on what it sees as the “world’s best public/private partnership model in agriculture,” namely, the Indian tobacco auction system, which was introduced in 1984.

ITC made the point that while flue-cured tobacco occupied less than 0.10 percent of the country’s total arable land area, it was an important, sustainable commercial crop, generating enormous socioeconomic benefits in terms of agricultural employment, farm incomes, revenue generation and foreign exchange earnings. In part, this was down to the Tobacco Board’s e-auction system for this type, which provided for fair assessments of growers’ bales in respect of both weight and grading, healthy competition, fair prices and, importantly, prompt digital payments.

Also accentuating the positive was Frederick de Cramer, a tobacco industry doyen now involved with the production of Latakia tobacco. In Turkey, opportunities were being created by a tobacco law instigated last year requiring cigarette manufacturers to include 10 percent locally grown Virginia in their blends, he said, a figure that was due to rise to 30 percent in four years. Local cut rag operations that bought domestically grown sun-cured Virginia (SCV) and flue-cured Virginia (FCV) were looking into the possibility of providing access to their leaf sources to cigarette manufacturers. But de Cramer pointed out, too, that, currently, there was a need to apply better agricultural practices to increase the quality of the SCV and FCV produced in Turkey for both the domestic and export markets. And there was a need, too, for a good big-leaf processing line.

Turning to the issue of locally grown classical oriental tobacco, de Cramer said a reduction in demand for these varieties was causing concern for the long term. Multinational tobacco manufacturers had reduced their demand for these varieties for a number of reasons but mainly because of price/cost considerations. In recent months, though, the Turkish lira had devalued substantially against the dollar, and it was possible that demand for Turkish oriental tobacco could increase. But there is danger nevertheless, said de Cramer. While classical oriental tobacco had been and still was a vital component of high-quality American-blend cigarettes, multinational manufacturers were no longer supporting this traditional leaf as they had in the past. Demand had been reduced due to several factors, including the switch to nontraditional cigarettes such as e-cigarettes, lower oriental inclusion rates in traditional blends, even the removal of such tobaccos completely from some blends, and import duties in some countries imposing de facto import restrictions.

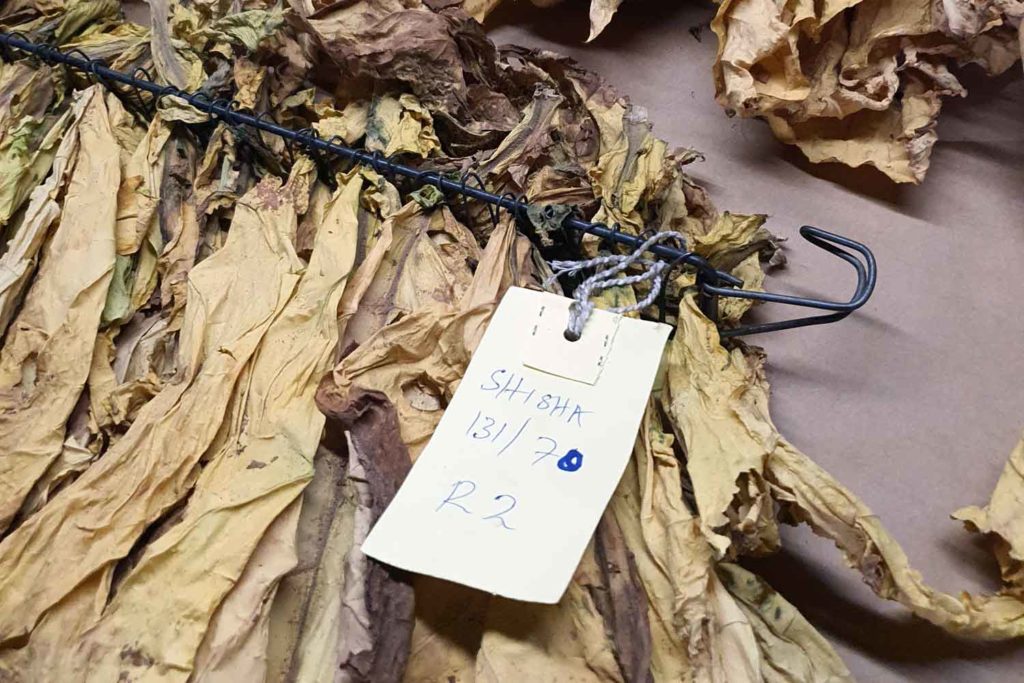

(Photo: Tobacco Reporter archive)

The Greek Outlook

This partly mirrors what has been happening in Greece, where the future of the leaf tobacco industry is apparently under threat. I say “apparently” because industry experts in Greece are reluctant to say anything even though problems have been apparent since at least 2019. Little wonder perhaps. From what I can surmise, it seems possible that within three years to 10 years, Greece may no longer produce classical oriental tobacco—possibly no tobacco at all.

Assuming this is correct, how did things reach such a pass? For many years, the Greek tobacco industry operated in a country that supported production. The industry had easy access to finance, good extension services and a lot of skilled growers who, in general, were paid fairly. It had good processing facilities, a stable customer base and well-established export systems.

It is true that production levels were sometimes out of kilter with the market, but there were multiple reasons for this, not all of which were within the control of the Greek industry. And, in any case, production of classical varieties of oriental tobacco were cut back hugely in 2006 to 20,000 tons a year after the decoupling of EU crop-specific agricultural support, a move that seemed to stabilize the industry and align it more closely with the new market realities.

Clearly, what is at the root of the problem is demand. Again, from what I can surmise, the classical oriental tobacco crop last year fell to 11,900 tons, the smallest crop of classical oriental tobacco ever in Greece, while next year’s production might or might not hit 10,000 tons. Why? One major factor is that Philip Morris International, which had, for a number of years post-decoupling, agreed to buy a significant proportion of Greece’s crop, pulled out of that agreement in 2019, partly, I guess, because of its commitment to switch its production away from traditional cigarettes to IQOS. Subsequently, its orders placed with Greek processors seem to have fallen to a fifth or even a tenth of what they were.

Is there any way back for Greece? Possibly not. Even if demand started to pick up, the industry would have to attract a new generation of growers to tobacco, which, on current evidence, might prove difficult. But never say never. There are many unknowns currently affecting the tobacco industry, not the least of which concerns how successful heated-tobacco products and e-cigarettes will be in a world starting to concentrate on environmental issues. And the issue of filters cannot be ignored. Will they be banned eventually, which would make sense environmentally? And if they are banned, along with flavors, how do you make a decent cigarette? Well, one obvious way would be to use classical oriental tobacco.