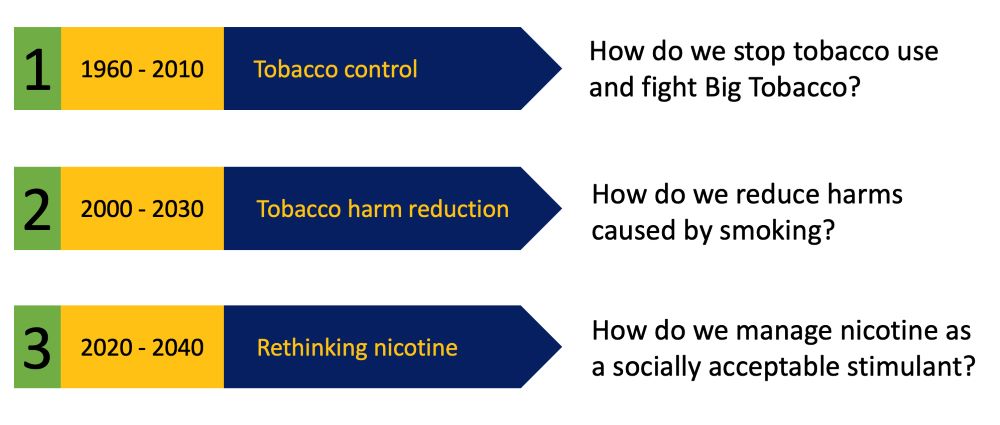

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has submitted a proposal to limit the amount of nicotine in tobacco products, reports CNN.

The FDA has been discussing limiting nicotine levels since 2018, and this week, the FDA submitted the proposal to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). This move comes as the Biden administration enters into its last weeks and President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take office in January 2025.

“A proposed product standard to establish a maximum nicotine level to reduce the addictiveness of cigarettes and certain combusted tobacco products, when finalized, would be among the most impactful population-level actions in the history of U.S. tobacco product regulation,” the FDA said in a statement.

“Once finalized, this rule could be a game-changer in our nation’s efforts to eliminate tobacco use,” said Harold Wimmer, president and CEO of the American Lung Association. “Making tobacco products nonaddictive would dramatically reduce the number of young people who become hooked when they are experimenting. To fully address the toll of tobacco on our nation’s health and across all communities, it is critical to reduce nicotine levels to nonaddictive levels in all commercial tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.”

“Certainly, there would be individuals who would benefit from substantially lower nicotine levels and find it easier to quit,” said Rose Marie Robertson, a cardiologist and chief science officer at the American Heart Association. “It’s really hard to quit. I’ve seen patients over many years who have gotten the wake-up call with a heart attack or a stroke and really want to improve their health and reduce their risk, but it’s just very, very hard to do.”

The submitted proposal does not mean that there will be any immediate changes. The OMB’s approval process can take months, and there must be a public comment period. It is likely that the tobacco industry will sue the government as well, as has been seen with other proposed regulations.

It is unclear what will happen with the proposal following the change in presidency. In Trump’s first term, the Trump administration signaled that it wanted to limit nicotine, but during this year’s election season, the tobacco industry donated heavily to Republicans, and Trump’s pick for chief of staff was previously a tobacco lobbyist.