Without offering locally relevant cessation tools, prohibition is doomed to fail.

By Sudhanshu Patwardhan

Bhutan, a country that measures its riches in terms of “gross national happiness,” may have become an unsuspecting victim of a new form of imperialism: health imperialism. A blind copy-paste of Western tobacco control policies, worsened by local gold-plating, may have landed Bhutan in a mess. A visit to the landlocked nation gave the author a unique insight into how prohibition of tobacco without offering locally relevant and innovative tobacco cessation tools threaten this Shangri-la.

The Forbidden Kingdom

A series of district-wide tobacco control measures in Bhutan from the 1980s culminated in the declaration of a nationwide ban on the sale of tobacco products in 2004 through a resolution of the National Assembly. Overnight, Bhutan became a poster child of global tobacco control, an emerging David against the Goliath of transnational tobacco companies. Nanny statists got a lifeline, and the “p” word—prohibition—was resurrected after successive failures of over 150 years in alcohol and drug prohibition movements. The Tobacco Control Act of 2010 further enshrined into law restricted access, availability and appeal of tobacco products and gave sweeping powers for arresting those selling or even possessing tax-unpaid tobacco for personal consumption. Bhutan was all set to become a tobacco-free society. A happy nation was also going to become healthier. In theory.

Market Forces Take Over

The roller-coaster ride between 2010 and 2019 is captured in the World Health Organization’s regional office’s 2019 publication The Big Ban: Bhutan’s journey toward a tobacco-free society. A big achievement in this period was visible reduction in public place smoking. Otherwise, the optimistic title belies the details of the failed ban confessed in the publication. It is a classic tale of good intentions scuppered by poor execution. A highlight of the data reported there is the difficulty in enforcing the ban, evidenced by availability of tobacco products below the counter in most shops in Bhutan. Tobacco use among 13-year-olds to 15-year-olds went up from 24 percent in 2006 to 30 percent in 2013 based on the Global Youth Tobacco Survey findings. The severe penalties required by the initial law resulted in more than 80 people being imprisoned between 2010 and 2013. There was growing discontent about the disproportionality of the penalties among the people of a nation gradually moving from a benevolent absolute monarchy to a democratic constitutional monarchy. Public furor and rethinking among the lawmakers resulted in amendments and milder punishments, and the law’s “claws (were) trimmed,” states the WHO report. Between 2010 and 2014, permissible quantity for personal possession was steadily increased for both smoked and smokeless tobacco products. The ban and its enforcement were proving ineffective and untenable. And then Covid-19 happened.

Reversal of a Failed Ban

The government was obviously losing revenue due to the flourishing black market of smoked and smokeless tobacco products smuggled from India and elsewhere. The fear of tobacco smugglers bringing in the Covid-19 virus was enough excuse to act decisively. In July 2021, the government amended the 2010 Act, thus lifting a decade long ban on local tobacco sales.

The pragmatism of the politicians who reversed the ban presents a sharp contrast to the previous prohibitionist policy. Today, sales and consumption continue, and based on the most recent (2019) WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) data, 24 percent of those between ages 15 and 60 currently use tobacco products. Sadly, the ban did not make Bhutan a tobacco-free society. Anecdotally, e-cigarettes are also available now in some grocery stores in the capital, Thimphu, and attracting use among smokers and never-smokers. These are not regulated nor used as smoking cessation tools, presenting another area of concern for public health. A ban may not be the answer for these products either. Regulation that balances current smokers’ needs for safer alternatives versus prevention of uptake by the youth and nonsmokers will be key.

Peering Through an ‘Addiction’ Lens

I first read about the ban’s overall failure in the 2019 WHO report and then heard about the reversal of the ban during the global Covid-19 pandemic. How did Bhutan land in this situation? There is, of course, economics at play: demand, supply and something to do with a genie being out of the bottle. When I put my doctor’s hat on, a key explanation stares at me: lack of quitting support for the existing 120,000 tobacco users. Reams of self-congratulatory publications and numerous WHO awards to Bhutan since the 1990s have focused on success in awareness-building and restricting access and use. The famous case of the Buddhist monk who was jailed for three years in 2011 for the possession of $2.54 worth of tax-unpaid tobacco misses the point that he was very likely addicted to tobacco and may have needed more than punishment to quit. In the absence of availability of tobacco products, it should have been a human right for him to have access to safer nicotine to manage nicotine withdrawals and achieve craving relief. This assessment should not be used to vilify tobacco users. Instead, it should be a reminder to those in tobacco control that preaching to nicotine-dependent users without offering alternatives is not enough and also unethical. A key demand-side reduction measure, to use Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) vocabulary, is that of providing tobacco dependence treatment and services. This is covered under FCTC Article 14 but rarely implemented in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), Bhutan included. I saw firsthand recently the country’s struggles with rising tobacco use coupled with a lack of cessation products and services.

Tobacco Cessation: The Poor, High-Maintenance Cousin

In Bhutan, like in most LMICs, overall tobacco control is run by public health experts, and tobacco cessation specifically (and separately) falls under the remit of psychiatrists. Neither groups are excited by tobacco cessation for a variety of reasons. Public health professionals often have little or no experience in treating individual patients and have increasingly been sold a unidimensional narrative that the tobacco epidemic is singularly driven by the commercial vested interests of tobacco companies (the “vector”). For them, the tobacco user is a victim of the tobacco industry, should be labeled an addict and then preached at to quit. Psychiatrists, on the other hand, are generally geared toward treating established mental health conditions and severe mental illnesses and even within the “de-addiction” field prioritize substance abuse treatment and alcohol de-addiction over tobacco cessation. Tobacco cessation with nicotine-replacement therapy and other pharmacological interventions are costly and need a level of training and qualification to prescribe—and are therefore cost-prohibitive to be offered at scale. They are also not without their failures, give around 20 percent quit rates at one year in controlled clinical studies and much less success in real-world settings. The success of quitting cold turkey is overrated and often drives policymakers’ wrong beliefs and attitudes about the ease of quitting. Public health tobacco control awareness campaigns and advocacy, on the other hand, are highly visible, scalable, inherently worthy endeavors, and most do not require impact assessment as proof of success. The FCTC’s Article 14 thus remains a neglected tool for reducing harms from tobacco globally and receives little or no funding from international donors and national governments nor any interest from pharmaceutical companies or tobacco companies to innovate in.

Safer Nicotine Not Widely Available in Bhutan

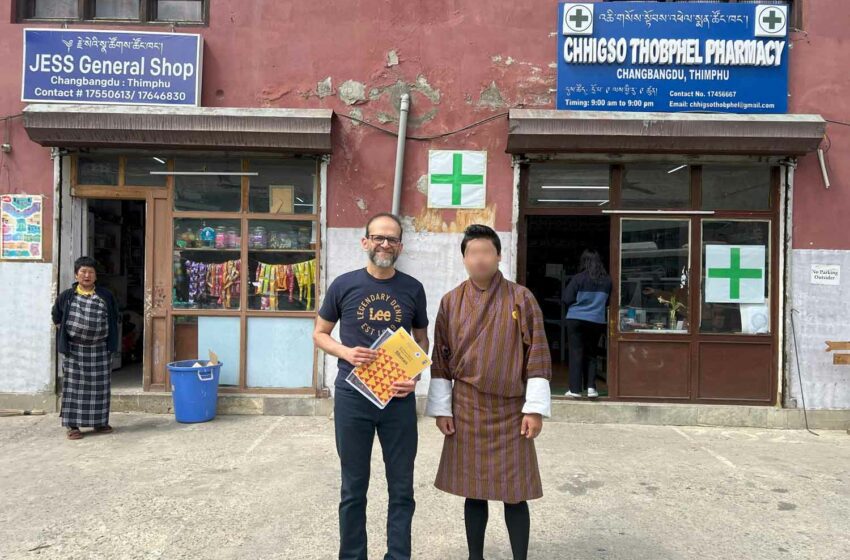

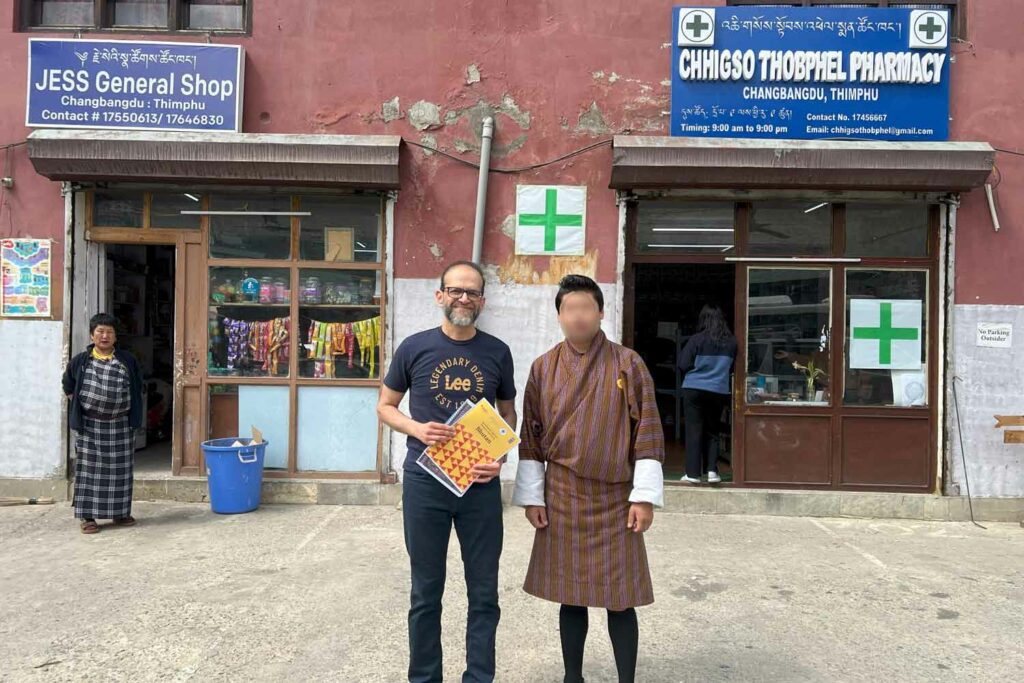

Nicotine illiteracy among healthcare professionals and lack of availability of safer nicotine alternatives can translate into poor quitting among tobacco user patients. From my field visits to pharmacies and discussions with frontline healthcare professionals in Bhutan, I noted that 2 mg and 4 mg nicotine gums have only recently become available in some pharmacies in Thimphu, but patches are not stocked. Patients come and buy these over the counter, but there is little record of how long they take it for, their quit and relapse rates and whether their doctors support them in their quit journeys. Varenicline or bupropion are not available for cessation. When called, the “national quitline,” contrary to the claim of the 2019 and 2024 WHO publications, do not deal with tobacco cessation support. Most of the healthcare professionals in Bhutan receive their undergraduate and graduate training in India, Sri Lanka and other nearby Asian countries. Similar to the rest of the world, doctors in Bhutan are not confident about prescribing nicotine-replacement therapy and may harbor misperceptions about nicotine itself. They have not received any tobacco cessation-related training in the past five years, and nicotine-replacement therapy is not available for free or at subsidized prices anymore, unlike other medications in Bhutan.

Navel-Gazing Time for All?

The backpedaling by Bhutan on the tobacco ban has not been reported or analyzed widely enough. Bhutan’s failure to rein in tobacco sales and increased use, despite a ban, should be a wake-up call for all parties involved. What was touted as a role model for other countries for eliminating harms from tobacco has instead become a cautionary tale for poor policymaking done to pander to international funders and organizations. The undue influence of a select few Western nations in national health policymaking for LMICs is also a matter of concern as the global geopolitical order rapidly morphs. Projects such as FCTC 2030, funded by the U.K., Norway and Australia, continue to churn out reports such as the Investment Case for Tobacco Control in Bhutan (WHO/UNDP, February 2024), ignoring lessons from the ban, mostly unaware of capacity issues on the ground and not addressing the need of current tobacco users for safer nicotine alternatives. Emergent strong economies such as China and India will no longer tolerate meddling by past colonial powers and imperialist nations in their health policies, but neither should other LMICs.

Toward Gross National Health

For a nation of around 750,000 people, tobacco use is claimed to kill between 200 people and 400 people every year—all preventable deaths (side note: the data for the same year varies dramatically between two WHO reports). Global tobacco control has failed Bhutanese tobacco users and their families. For a nation built on principles of sustainability, risky forms of smoked and smokeless tobacco products have no place in society. The mountains, the clean air, the happy smiles and peace-loving people of Bhutan deserve to own tobacco control initiatives, not be made to adopt hand-me-down Western ideologies or policies. That will require the doctors and pharmacists in Bhutan to understand the science of tobacco cessation and harm reduction and make quitting sexy. Availability of nicotine-replacement therapy products, innovation in safer nicotine alternatives and improved cessation services will need to be ensured and incentivized by the government. That has the potential to keep their nation happier and healthier for the coming generations.

Disclaimer: The author’s work here or elsewhere is dedicated to using ethical and scientific evidence-based approaches to eliminate harms from all risky forms of smoked and smokeless tobacco products. The article is based on the author’s personal conversations with experts and lay people in Bhutan and from shop visits and an analysis of two of the most recent WHO reports on this topic. The intent of this article is to shine a light on a vulnerable LMIC’s experience with unchecked health imperialism to create insight and debate on the impact and implications of such practices. The author holds utmost respect for the nation, the policymakers and the people of Bhutan.