The FDA's decision to authorize Njoy menthol products is a significant step forward.Read More

Tags :flavors

Examining the impact of flavored e-cigarettes on adult smokers: insights from a three-month experimental study Read More

The presentation will provide an overview of the evidence that led to the proposed rules.Read More

The idea that e-cigarette flavors hook kids is simple, compelling and false.Read More

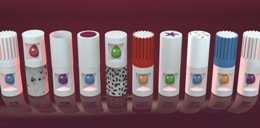

Are choices key to successful switching?Read More

Increasingly popular, crushable filters may very well breach the confines of their niche status.Read More