Colin Mendelsohn, board member and founding chairman of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, detailed “the very sad state” of vapor regulation in his country. Australia, he said, is the only Western democracy to effectively ban nicotine liquid.

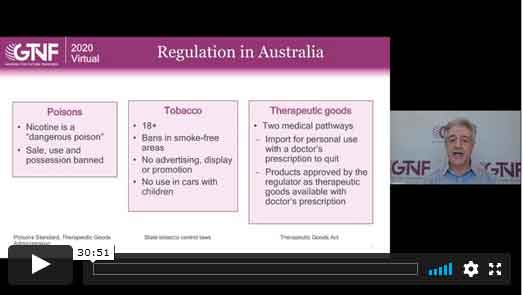

Australia classifies nicotine as a dangerous poison in the same category as arsenic, and consequently, its sale and use are criminal offenses unless accompanied by a doctor’s prescription. Violators of the nicotine ban face penalties of up to AUD45,000 ($32,230) and up to two years imprisonment, depending on the state. The law makes an exception for nicotine-replacement products and cigarettes, ironically allowing users to consume nicotine by combusting tobacco leaves—the riskiest delivery method—but not by vaporizing e-liquid, which is generally believed to be less harmful to health.

Vapor products are also subject to the tobacco law and the therapeutic goods law. Among other things, this means vapor companies are not allowed to advertise or display their products, and consumers cannot vape in their personal vehicles when there are children present. The therapeutic goods law allows vapers to import products for personal use with a doctor’s prescription, but this remains very much a theoretical scenario. “People aren’t doing it,” said Mendelsohn.

The hostile climate to vaping is extracting a serious human cost. Mendelsohn displayed a graph comparing the development of smoking rates in the U.S., the U.K. and Australia. After 2013, when vaping became widespread, the declines accelerated in the U.S. and the U.K. but flatlined in Australia. Whereas the share of smokers decreased by a full percent per year in the U.S. and 0.8 percent per year in the U.K., the annual decline in Australia stagnated at 0.3 percent—one third of the rate in the other countries. In 2019, the smoking rate was 14.7 percent in Australia, 13.9 percent in in England and 13.7 percent in the U.S.

“We can’t say for sure it’s all due to vaping, but vaping is playing a major role because Australia is doing everything else,” said Mendelsohn, referring to the country’s draconian tobacco control policies. “We have very strict tobacco control laws, the highest cigarette prices in the world, plain packaging—and yet smoking is not changing.”

Other unintended consequences of the ban include black market sales, the relocation of Australian businesses to New Zealand (from where they sell their products to Australia) and a thriving do-it-yourself business in which vapers import nicotine to create their own e-liquids (and occasionally get poisoned by their concoctions.)

Despite the unwelcoming environment, Mendelsohn is cautiously optimistic that things may improve for Australian vapers after Health Minister Greg Hunt tried to ram a ban on nicotine imports through Parliament and suffered a major backlash. Opponents “melted the phone lines” to their members of Parliament, according to Mendelsohn. Twenty-eight backbenchers sent a letter to health minister; a petition against the proposed legislation gained 70,000 signatures in three days; and 95 percent of vapers indicated in a survey that the decision would influence their vote.

In the end, the minister backed down. The plan has been delayed by six months; a streamlined version will be introduced on Jan. 1, 2021. According to Mendelsohn, vaping has become a political decision. “We are not going [to] change the bureaucrats, but the politicians are getting it—and they will decide,” he says. “One consideration that will weigh heavily in their considerations is that vapers vote. We now have a lot of vapers who will vote according to this issue. As we know from the U.S., vaping for many voters is a ‘single issue.’ If you know vaping will save your life, you will pick the party that supports you.”

In addition, notes Mendelsohn, lawmakers have become more receptive to the evidence supporting vaping as less risky than smoking. “The decision will be made in Canberra, and we hope the politicians will stand up for this. So far, the evidence is promising.”