Malawi seeks to reduce its heavy dependence on tobacco.

By Taco Tuinstra

The impacts of Malawi’s balance-of-trade crisis were visible in late March even to an infrequent Western visitor who could afford to stay at an upscale hotel. Certain items on the room service menu were consistently out of stock, for example, while getting around Lilongwe required queuing for gasoline and hoping the petrol station would not run dry before the driver reached the pump.

Because Malawi imports more goods and services than it exports, it suffers a chronic shortage of hard currency. In 2020, the latest year for which figures are available, the country’s import bill was $2.8 billion, versus exports of only $800 million, according to the National Statistics Office. With not enough U.S. dollars to pay for imports, many foreign-made goods were simply unavailable.

For Malawi’s well-heeled international guests, the shortages represent mere inconveniences. Upon return to their home countries, they will be able to generously make up for the missed food items and travel without worrying about fuel. For the average Malawian, however, the trade deficit represents a real problem. Among other things, the dearth of foreign currency prevented the nation from importing enough fertilizer for its Maize and other crops this year, spelling trouble for food security and social cohesion. While Malawi was peaceful during Tobacco Reporter’s visit in late March, some feared civil unrest. “It’s coming,” warned an industry veteran.

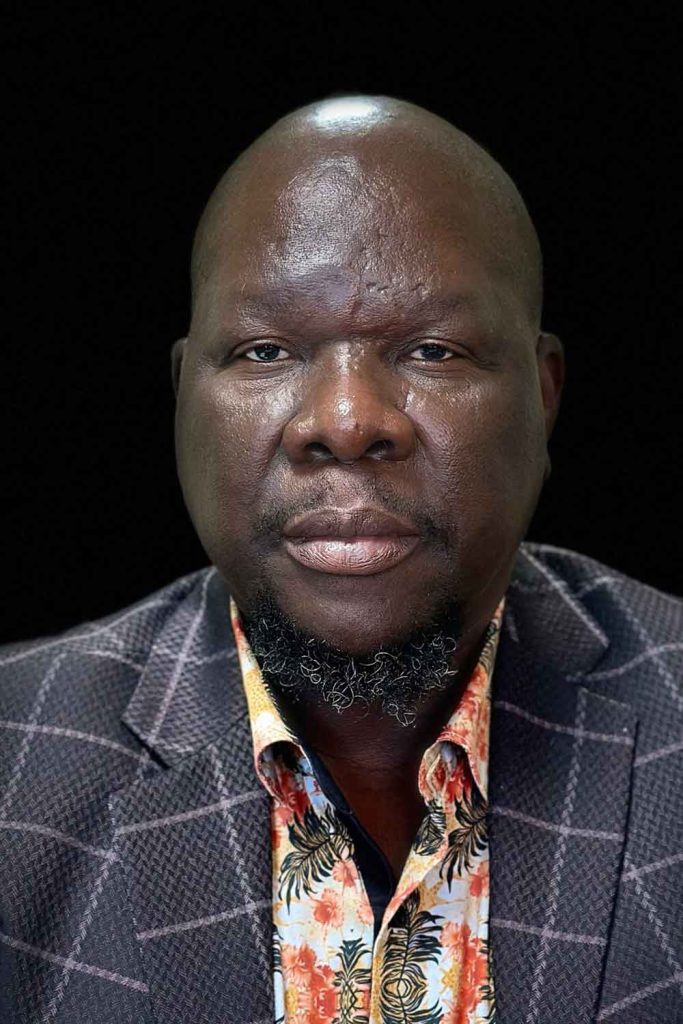

Visit the countryside in April/May, and you will see how people’s lives change when the tobacco markets open. If the markets fail, however, there will be poverty in the villages.

Nixon Lita, CEO, TAMA Farmer’s Trust

One cause of Malawi’s economic problems is the fact that it relies too heavily on a single commodity. Tobacco accounts for between 12 percent and 15 percent of Malawi’s gross domestic product and between 40 percent and 70 percent of export earnings, depending on who you ask and on the season. Cultivation alone employs nearly half a million people, according to the Tobacco Commission, which regulates the trade. Those figures make Malawi the world’s most tobacco-dependent country.

They also leave Malawi vulnerable to factors outside its control, including climate change and global cigarette sales. “Visit the countryside in April/May, and you will see how people’s lives change when the tobacco markets open,” says Nixon Lita, CEO of the TAMA Farmers Trust, describing the influx of cash at the start of each selling season. “If the markets fail, however, there will be poverty in the villages.”

Last year is a case in point. Due to unfavorable climate conditions during the growing season, Malawi produced only 85.09 million kg of tobacco in 2022—the lowest volume in a decade, according to the Tobacco Commission. Despite higher per-kilo prices than in 2021, farmers earned just $182.12 million from their leaf sales last year. The reduced inflow of foreign currency in 2022 has left Malawi struggling even harder than usual to import essential items. The money made from this season’s larger crop (see “Back to Normal”) is unlikely to make up for the shortfall.

Malawi’s overreliance on tobacco will become an even greater problem as global cigarette consumption stagnates. Already, the country’s leaf sales are down considerably from only a few years ago. Between 2016 and 2021, tobacco exports in real terms dropped by 42 percent, according to the World Bank. While local merchants are confident that Malawian burley—the country’s predominant tobacco variety—will continue to find buyers in the near future (see “Enduring Demand“), they are acutely aware that the industry should start preparing for a future with less tobacco, especially as the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control measures to discourage cigarette consumption start to bite.

Malawi tobacco growers benefit from structured markets, which give them access to customers worldwide. Such infrastructure does not exist for many of the country’s other commodities. The video shows leaf being auctioned at the Lilongwe sales floors.

Spreading the Risk

To broaden Malawi’s economic base, stakeholders have stepped up efforts to develop other sectors. The TAMA Farmers Trust, for example, expanded its mandate in 2019. Originally established to represent only tobacco farmers, the organization is now helping its members produce other crops as well. Tobacco merchants such as Limbe Leaf Tobacco Co. (LLTC) and Alliance One Tobacco Malawi (AOTM), too, are encouraging diversification. Leveraging their existing farmer-support structures, they are now also disseminating inputs and agronomic advice for nontobacco crops to their contracted growers.

Another big push comes from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (FSFW), which is an independent U.S. nonprofit organization that is funded by annual gifts from PMI Global Services. Established to “end smoking in this generation,” the FSFW focuses its grantmaking and charitable activities in three categories: health and science research aimed at helping smokers quit or switch to less harmful products, industry transformation and agricultural diversification.

We should not make the same mistake as with tobacco by developing just one value chain.

Candida Nakhumwa, vice president and Malawi country director, Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

The foundation’s agricultural diversification objectives include ensuring that smallholder farmers in Malawi impacted by the declining demand for tobacco are supported to find sustainable alternative livelihoods. To advance these objectives, the FSFW has made grants to set up two institutions—the Centre for Agricultural Transformation (CAT), a science, business and technology incubation hub, and the MwAPATA Institute, an independent agricultural policy think tank that conducts research to inform and improve agricultural-related policies.

Candida Nakhumwa, FSFW vice president and country director in Malawi, stresses the importance of developing multiple value chains simultaneously. “We should not make the same mistake as with tobacco by developing just one,” she says. In selecting alternative commodities, Nakhumwa urges Malawi to prioritize both exports and import substitution. “We are spending precious foreign exchange on importing things that we should be producing domestically,” she says. “For example, we can make cooking oil from soya beans or sunflower and use that as an import substitute.” Soya beans and sunflower, along with traditional Malawi crops such as groundnuts, also enjoy growing demand internationally, representing export potential.

Building Markets

For crops like soya bean, sunflower and groundnuts to succeed, however, Malawi will need to replicate some of the factors that have allowed tobacco to thrive, notably infrastructure and a deliberate focus on productivity. Over the years, the Malawi government gave lots of support to tobacco at the expense of other crops that also had potential, according to Nakhumwa. As a result, the markets for those other value chains remain underdeveloped.

“The fact that tobacco has a structured market in Malawi, with auction floors and contracting companies, means that leaf growers have access to buyers worldwide—something that is not necessarily the case for producers of other crops,” says Nakhumwa. Without a structured market, producers of nontobacco crops will simply be trading in Malawi kwacha instead of earning hard currency on the global market.

A structured market also gives confidence to financiers. “Tobacco farmers are not paid in cash; they receive their payments through the bank—so the lenders know they will recover whatever they loaned to the farmer,” says Nakhumwa. Access to finance in turn means access to agricultural inputs, including inorganic fertilizers, which are imported.

In addition, tobacco has benefited from research and agronomic advice, both through the leaf merchants and the government’s Agricultural Research and Extension Service Trust. Such services have historically been provided at much lower levels to other crops, although this is starting to change as stakeholders adjust to evolving market conditions.

Due to suboptimal agricultural practices, nontobacco farmers in Malawi are producing at only 30 percent to 40 percent of their potential, according to Nakhumwa. The country’s soils suffer from high acidity and low nutrient levels. These can be fixed using both organic and inorganic fertilizers. However, with commercial banks charging interest rates of 20 percent to 30 percent, tools to improve the soil, such as agricultural lime and inorganic fertilizer, remain out of reach for many smallholder farmers.

Low productivity means that even though there is demand for Malawi’s nontobacco crops, the country is in many cases unable to satisfy it sustainably. “When a customer in South Africa signs a forward contract, he will want assurance that the goods are going to be delivered consistently,” says Nakhumwa. “If we can supply for only two months and then run dry, we are no longer an attractive supplier for them. The customers may in that case prefer to deal with a seller in Brazil or elsewhere who can guarantee supply.” This is why the FSFW is focusing on enhancing productivity at the farmer level and creating new markets through the CAT.

Strengthening Skills, Raising Productivity and Creating New Markets

The CAT aims to boost agricultural productivity through science, technology and innovation while helping innovators turn their ideas into sustainable agribusinesses to create new markets for the alternative commodities produced by smallholders. At a demonstration farm on the outskirts of Lilongwe, the organization offers a platform for a wide range of private sector partners to showcase technologies to help farmers optimize their operations.

Alongside technologies such as irrigation and ground sensors, the farm features different varieties of maize, groundnut, soya beans, rice and sunflower, among other crops. It also works with agronomists to transfer knowledge: What happens if you plant 10 cm apart or practice double-row planting? What happens if you tweak the amount of fertilizer? According to CAT Executive Director Macleod Nkhoma, such demonstration plots are an effective way to disseminate information to smallholder farmers and promote the adoption of technology, especially in a country with low literacy rates like Malawi.

In addition to its work on the farm, the CAT helps agricultural entrepreneurs with skills that enable them to access finance and grow their agribusinesses while providing markets to smallholder farmers. “Banks tend to be wary of unstructured markets,” says Macleod. “They view those value chains as very risky.” By supporting the development of these agribusinesses, the CAT helps them to become bankable.

Already, the center has supported several agricultural ventures, including a project by Hortinet that seeks to reinvigorate Malawi’s dormant banana business through tissue culture (see “From Imports to Orchards”) and an initiative by JAT Investments, which aims to replace the button mushrooms that are currently imported into Malawi with domestically cultivated varieties (see “Fungi Fever“).

The CAT is helping Hortinet to expand its farmer base from 200 to 700 contracted growers. “Without CAT’s support, we would not have had the capacity to supply that many growers with our banana plantlets,” says Hortinet Executive Director Frank Washoni. JAT Investments benefited from CAT assistance in procuring seeds (spawn) and infrastructure in support of mushroom production. “The CAT helped us procure seed, infrastructure and training, allowing us to grow our growers’ network from two to seven farmers club.” says JAT Investments Operations Director Temwani Gunda. “It we had to work on our own, it would have taken much longer.”

In terms of weight, Alliance One Tobacco Malawi’s contracted farmers already produce four times more food than tobacco.

Simon Peverelle, managing director, AOTM

The Tone at the Top

To live up to their potential, the nontobacco crops will also need better policy frameworks. According to MwAPATA Executive Director William Chadza, export bans and foreign exchange quota currently disincentivize production. “Farmers are often unable to access hard currency to import agricultural inputs in time for the growing season,” he says. In addition, some government market interventions, frequent policy reversals and the unpredictable business environment limit private investments in the agricultural sector. Contradictory policies relating to land and crops present a hurdle as well, according to Chadza.

Encouragingly, Malawi’s leadership increasingly appreciates the need to broaden Malawi’s economic base. Whereas the government in the past may have been reluctant to acknowledge the changing situation on the global tobacco market, it now appears more cognizant of the new realities. At the opening of the 2022 marketing tobacco season, Malawi President Lazarus Chakwera openly called for a diversification strategy. “The tone at the top is important,” says Nakhumwa. “If the leaders cannot acknowledge that there is a problem and we need to pivot, stakeholders will not rally behind you.”

Perhaps surprisingly to some, diversification has also been embraced by the tobacco industry. LLTC is supporting growers with certified food crop seeds grown on company farms in the Kasungu district while researching and developing other food crops for exports. It has collaborated with Feed the Future USAID and will be rolling out low-tech irrigation systems to boost productivity. AOTM has made a big bet on groundnuts (see “A Gamble on Goobers”), helping its contracted farmers increase yields and quality with improved varieties, farming equipment and agronomic advice. In March 2022, the company opened a groundnut processing facility in Lilongwe with the capacity to process 50,000 tons per year.

It took us more than 50 years to develop the tobacco industry to where it is now,” he says. “There is no way other crops will all of a sudden replace tobacco.

Joseph Malunga, CEO, Tobacco Commission

The merchants’ investments in productivity, meanwhile, have enabled tobacco farmers to double their yields, allowing them to produce the same volumes of leaf on fewer hectares and release land for food and other cash crops. Tobacco industry leaders see no contradiction between their support for nontobacco crops and their primary business, arguing that farmer livelihood sustainability is in their interest. “Diversification makes sense,” says Simon Peverelle, managing director of AOTM. In terms of weight, he points out, the company’s contracted farmers already produce four times more food than tobacco.

But even with government and industry behind diversification, it will take time for Malawi to overcome its heavy reliance on tobacco. Tobacco Commission CEO Joseph Malunga believes the golden leaf will remain a major crop in Malawi for years to come. “It took us more than 50 years to develop the tobacco industry to where it is now,” he says. “There is no way other crops will all of a sudden replace tobacco.”

Nonetheless, Malunga acknowledges that Malawi needs to spread its eggs over more than one basket. “It is dangerous for us as a country to rely on one thing because if something goes wrong, you are definitely in trouble,” he says. Rather than looking for commodities to replace tobacco, however, Malunga urges Malawi to promote crops that work alongside it, just like the leaf merchants have been integrating food crops into their tobacco operations.

Malawi has a long way to go, but through the combination of government, industry and nonprofit initiatives currently underway, it should be able to gradually develop a more diverse economy with multiple crops and livestock generating income, so that a bad season in one sector won’t automatically reverberate across the entire country. The stakes are high, witnessed by the economic difficulties in the wake of last year’s short tobacco crop. Success will mean not only greater food security but also more hard currency to import the items that Malawi cannot produce at home. With luck, it may even boost tourism, as the country’s struggling hospitality sector will be able to stock more of the items its foreign customers expect.