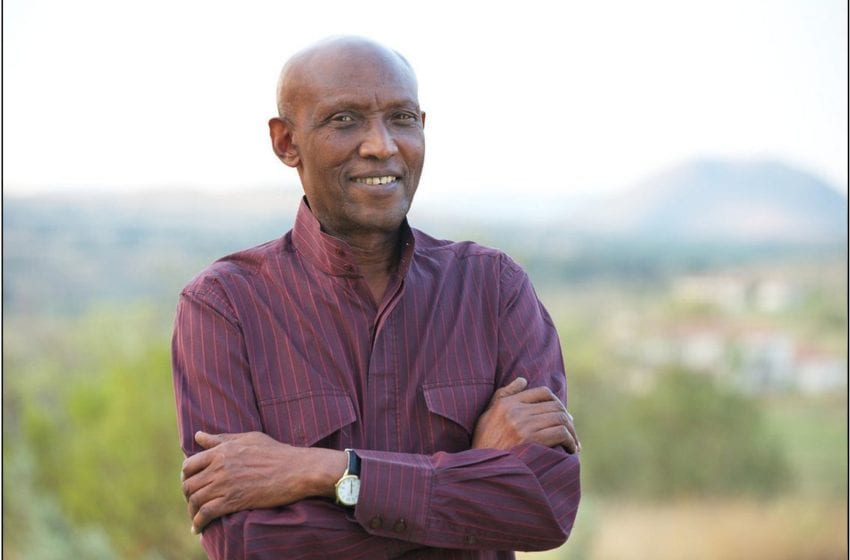

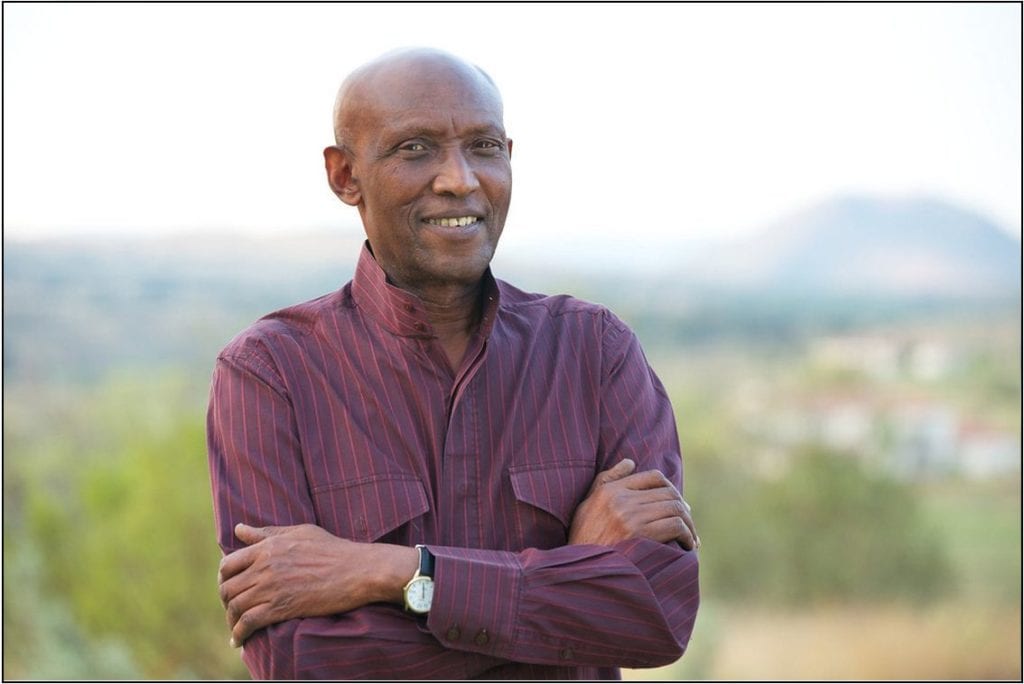

Tribert Rujugiro Ayabatwa, an industrialist with ties to the tobacco industry, has welcomed the removal of his name from a report linking him to extremism and illicit trade in Africa.

The April 2021 report, “An Unholy Alliance: Links Between Extremism and Illicit Trade in East Africa,” contained references to Tribert Rujugiro Ayabatwa and his PTG group of companies.

Through his legal counsel, Ayabatwa made representations to the legal counsel for the report’s author, Sir Ivor Roberts, as to Ayabatwa’s history as a Pan-African industrialist and philanthropist operating across Africa and the United Arab Emirates. All references to Ayabatwa in the Roberts’ report have now been removed.

Ayabatwa welcomes this development and is happy to put this matter behind him.

“Regrettably, due to the complexity in the persisting instability and conflict in eastern and central Africa, it is nearly impossible for foreign researchers and analysts to fully grasp positive and negative actors in the region,” said Senior Advisor David Himbara.

“In Ayabatwa’s case, for example, his Congo Tobacco Company has been the only manufacturing business operating in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo for over four decades. The company is one of the few providers of legitimate employment opportunities in a region devastated by instability and war. It is therefore ironic that Ayabatwa was lumped together with illicit trade and extremism in the Unholy Alliance: Links Between Extremism and Illicit Trade in East Africa report penned by Sir Roberts. “

Tribert Rujugiro Ayabatwa is the founder and controlling shareholder of the Pan African Tobacco Group, Africa’s largest indigenous manufacturer of tobacco products. The company, which in 2018 celebrated its 40th year of operations, manufactures cigarettes in Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and the United Arab Emirates.

Ayabatwa is also one of Africa’s leading philanthropists, according to a press release put out by him. He has invested in education, food security, afforestation and water-access. Through his non-profit foundation, Ayabatwa strives to help young people to gain the practical engineering experience required to enter the job market in Africa. More recently, Ayabatwa assisted governments in the battle against the Covid19 pandemic by contributing medical equipment and foodstuffs during the lockdowns.

Tobacco Reporter profiled the Pan African Tobacco Group in August 2013.