Alliance One’s seed breeders in Brazil are boosting crop quality and yields while improving disease resistance and tolerance for extreme weather conditions.

By Taco Tuinstra

Small may be beautiful, but in some cases, bigger is better. Take tobacco seeds, which range between 0.5 mm and 1 mm in diameter. A single gram of the material can contain a whopping 10,000 seeds.

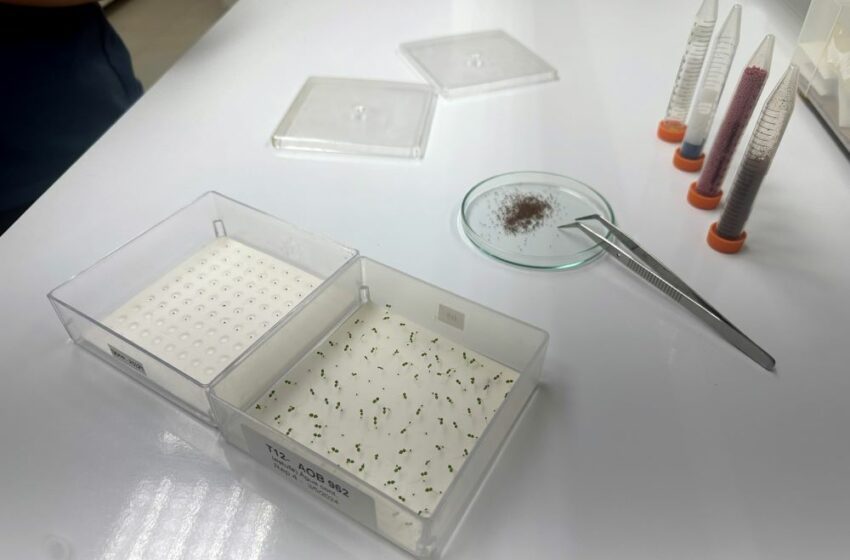

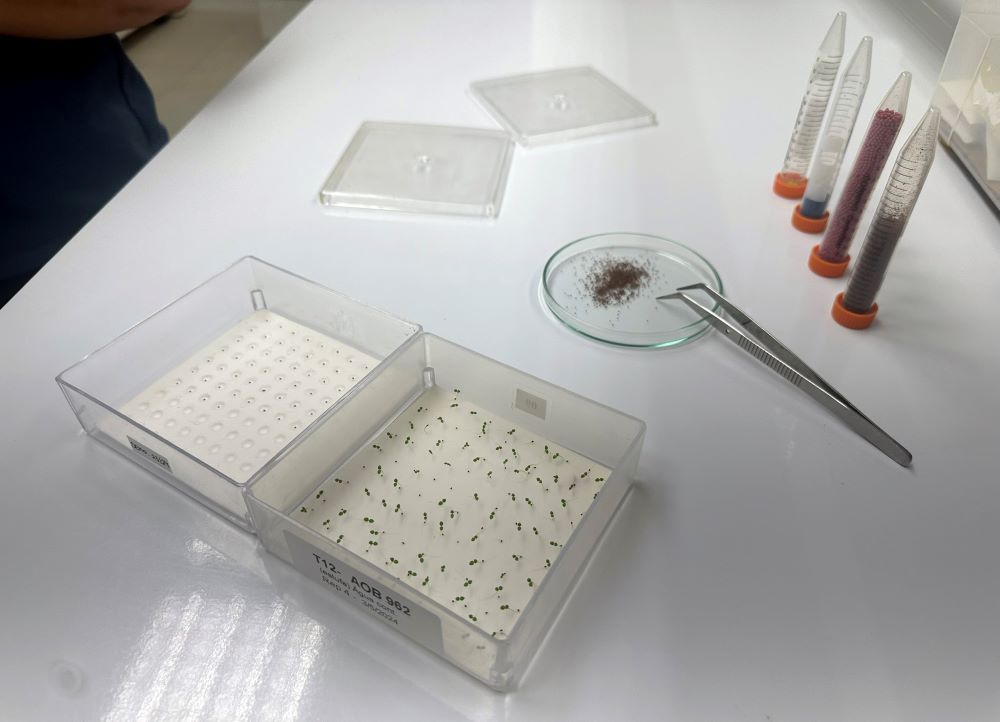

While that may seem efficient, seeds of that size are also difficult to handle. That’s why Alliance One International (AOI) has installed a pelleting machine at its Global Research, Development and Deployment Center in Passo do Sobrado, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil. In a process similar to that used by pharmaceutical companies in pill production, the device coats tobacco seeds with a mix of inert materials, including clay (drug companies use gelatin), to beef them up to more manageable dimensions. The seeds that exit the machine are up to 50 times bigger than the ones that go in, allowing the grower to plant them accurately.

The seed pelleting machine is only one of many investments at the center’s seed industrialization unit, which was inaugurated in January of this year. The facility also houses equipment that performs functions such threshing, grading, upgrading, drying and finishing—capabilities that help improve germination, stimulate healthy, consistent crop development and increase yield. The unit, which sits on an 82 ha farm housing greenhouses, laboratories and other key infrastructure, has an annual tobacco processing capacity of nearly 2 metric tons and the ability to pelletize more than 200,0000 cans of seed for sale each year.

In addition to commissioning new equipment, the unit has been expanding its skills base, hiring agronomists, biologists and agricultural engineers, among other professionals. During the Brazilian crop’s peak period, the center employs approximately 100 people.

The investments are part of AOI’s endeavor to strengthen its global function using existing capabilities. AOI has been a major supplier in Brazil’s tobacco seed market for years, selling not only to its contracted farmers but also to other leaf merchants. Roughly 40 percent of Brazil’s tobacco volume, or more than 100,000 hectares, are produced with AOI seeds, according to the company.

Keen to share the “fruits” of the labor in Passo do Sobrado with its other origins, the seed industrialization unit now also services AOI operations outside Brazil. “Basically, we transformed a local research center into a global research center,” says Helio Moura, AOI’s vice president of global crop science and value chain. Already supplying AOI in Guatemala, Argentina, Turkiye and Thailand, the center is currently in the process of entering additional markets.

According to Moura, the new unit provides the company with greater quality control and makes it possible for all activities to be governed by the company’s internal integrated quality management system. “Improved quality control opens doors to selling our seed in new markets at a faster speed, increases customer and farmer satisfaction, and drives efficiencies within our business,” he says.

Those are important benefits because seed breeding is a finicky, labor-intensive and time-consuming business. For example, plants must be pollinated flower by flower—a delicate process that doesn’t lend itself to mechanization. Getting the necessary approvals and certifications requires time too. When you add up all the steps, creating a new variety can take up to 10 years.

Moura likens the process to a funnel. “You have thousands of breeding lines, then we start selecting and narrowing it down until we are able to launch a better variety than we currently have,” he says, adding that there is always room for improvement. “The latest variety is not perfect, just superior to the previous one,” he observes.

The seed industrialization unit breeds for characteristics such as quality, yields, disease resistance and tolerance for extreme weather conditions, an attribute that has become increasingly important in recent years, as was tragically demonstrated in early May when Santa Cruz do Sul suffered the worst flash floods in living memory.

To ensure the required variation, the seed industrialization center houses a germplasm bank with thousands of “mothers” and “fathers” for burley, flue-cured and dark tobaccos, along with oriental styles. “We have access to more than 3,000 different tobacco varieties to cross and create new, unique strains,” says Moura. The resulting hybrids don’t produce seeds, which means they are impossible to replicate and thus guarantee return business for AOI. At least once every three years, seed samples in the germplasm bank are tested to make sure that they are germinating. That way, the company knows they will be available when it needs them.

With the help of DNA markers, AOI’s scientists identify the desirable qualities. Advancements in biotechnology have made the work quicker, easier and more accurate. “Thirty years ago, there were only a few tools for making selections; nowadays, instead of looking for the phenotypes in the fields, we can look inside the plant and see the genes,” marvels plant breeding supervisor Elaine Batista. What’s more, the cost of equipment has decreased significantly, allowing biologists to make selections quicker, more accurately and with less effort.

To ensure that the results of its research and development are rolled out correctly, AOI works closely with its contracted farmers. A new variety may deliver superior yields under controlled conditions, but if it’s improperly deployed in the field, the grower will not enjoy the full benefit. “So we spend much time training our growers on the correct way to work with the seeds,” says Moura.

Aware of the importance of capturing and retaining knowledge within their organization, the scientists meticulously document their work. “For every project, we create a business case and a project brief. If someone asks about it 10 years from now, we can save time and money,” says Moura, who at previous employers faced many situations in which colleagues inquired about a past project only to be told that the results were no longer available, forcing the company to reinvent the wheel. And while it may be tempting to document only the projects that worked, the seed industrialization unit insists on documenting both its successes and failures. “We don’t have the time or money to spend on things that don’t add value,” says Moura.

Even as demand for cigarettes stagnates and some nicotine users are switching to tobacco-free products, the work carried out at the seed industrialization unit is likely to remain relevant far into the future. As a respected flavorist pointed out during a recent Coresta meeting, consumers are able to tell the difference between nicotine created in a laboratory and nicotine derived from natural tobacco leaf. The depth of expertise and the sheer variety of genetic material housed in Passo do Sobrado will enable the unit to continue developing varieties that not only improve farmers’ operations but also meet and exceed consumers’ expectations for many years to come.