Machinery makers navigate supply chain challenges and customers’ changing product portfolios.

By George Gay

I was rummaging around in my office the other day, looking for something that I didn’t find, but as is often the case when rummaging, I did find many things for which I wasn’t looking. One of those things was a 20-year-old CD with the name of a tobacco machinery company on it and the title “Past, Present and Future,” and given that I was due to write a machinery story, I decided to take a look. The CD contained a PowerPoint presentation with 44 slides, 20 of them dedicated to the past, 23 to the present and one to the future. The future slide was unique not only in respect of it being the only one to address the future but also because it was blank except for the words “The Future.”

I don’t blame the presenter for being cautious. Predicting the future of the tobacco industry and its various sectors has always been fraught. The industry has been written off, prematurely, more times than I care to remember. But there is no doubt that, nowadays, the storm clouds appear to be more threatening, partly because they are coming from both within the tobacco industry and without. The range of regulations that govern the industry is becoming wider and more radical at a time when, partly in response to those regulations, the industry has chosen to transform itself.

So where is the industry, and, in particular, the tobacco machinery sector headed? It hardly seems worth stating that the future of the tobacco machinery business is linked to the future of the tobacco business, and, since the tobacco business is in decline, the tobacco machinery business must be in decline. End of story. But, of course, the situation is far more complex than that.

One obvious caveat that has to be added to this story concerns the offshoot the tobacco industry has grown, comprising lower risk tobacco and nicotine products. The problem here, however, is that it is not easy to predict whether this offshoot will flourish or atrophy. And, even if it does flourish, it is not easy to predict what the conversion rate of smokers to the consumption of these new types of products will be. It has to be remembered that if the traditional tobacco business is in decline, the opportunity for converting smokers diminishes, though this could be offset if nonsmokers were drawn to these products.

While some countries are encouraging, or at least not discouraging, such new products, others with huge populations are banning (India) or discouraging (China) them. In some countries, and for some time, entry to the new products markets will probably remain prohibitively expensive for many consumers, and there is the looming problem associated with environmental issues.

Optimization

Nevertheless, asked what the situation would look like in three years’ to five years’ time, Norbert Schulz-Nemak of TMQS had no hesitation in saying new-generation products (NGPs) will have taken a higher share of the overall market simply because such a conversion is a strategic goal of multinational companies. But combustible cigarettes would still be around because they were relatively cheap to buy and relatively easy to consume.

Was it the case, though, that the tobacco industry might split into a number of tobacco industries operating quite differently in various regions or countries in response to local regulatory environments and, therefore, the different products on sale within those regions or countries? It is not difficult to imagine a U.K. market without tobacco but with e-cigarettes completely divorced from an India market without e-cigarettes but with tobacco.

But in response, Schulz-Nemak said TMQS believed the only split would be in respect of technology. Tobacco manufacturers would continue a process started some time ago whereby they had concentrated the manufacture of their various products within specific manufacturing sites, thus optimizing the use of those sites. Focusing within individual sites on the machinery and processes necessary only for specific products provided for clear structures and logistics. Obviously, added Schulz-Nemak, there would be exceptions, but generally speaking, such developments were logical.

Maintaining Existing Equipment

Despite the transitions that the industry is going through, tobacco manufacturers large and small will clearly aim to maintain production levels and efficiencies within their traditional operations while keeping their businesses flexible enough to deal with future market trends. And this, according to TMQS, is leading many companies to be more cautious in their planning than they had been previously.

Catering for an increasing portfolio of NGPs and vaping products involved a costly exercise in bringing in new machinery, said Schulz-Nemak. And this was occurring at a time when combustible cigarettes still accounted for the major output of manufacturers—combustible cigarettes whose production lines also needed investments, both routine and regulation-specific, such as those requiring the manufacture of biodegradable filters.

Schulz-Nemak said that, in the case of secondary machinery, TMQS could help optimize production while keeping expenditure down. This potentially meant eliminating the need to invest in new machinery and then, perhaps, having to invest in new supporting infrastructure, different spares and materials. TMQS could offer machinery improvements, including those extending the life of equipment. It could provide everything from routine maintenance to repairs, conversions, extensions and modernizations. And it could offer support with spare parts and assembly groups.

Filling the Gaps

One change that has happened in the recent past is that tobacco manufacturers have tended to reduce their traditional product portfolios, which, presumably, has pushed more production toward the long-run end of the manufacturing continuum, and which, in turn, would have helped maintain demand for high-end, high-capacity machinery. But there is a flip side to this. When products are removed from the market, the holes created are seen as opportunities by entrepreneurs. This phenomenon is to be observed in many industries, and while it tends to be more subdued in the case of tobacco because taxes often dominate the retail prices of cigarettes, it happens. This raises the question of whether the inevitable gaps left in the market will see the emergence of more niche players requiring more modest machinery, either new or rebuilt, and simpler factory layouts.

In fact, Reto Iten of Iten Metals told me recently that the strength of demand for relatively old, slower cigarette making machinery was currently “amazing.” Demand was being driven by niche manufacturers that might want to produce, for instance, a CBD cigarette or an environmentally friendly cigarette, perhaps one using organic tobacco or one using only locally grown tobacco. With the right machines, such manufacturers, which were active on relatively small but attractive markets, could use high-quality cut rag to make good-tasting cigarettes.

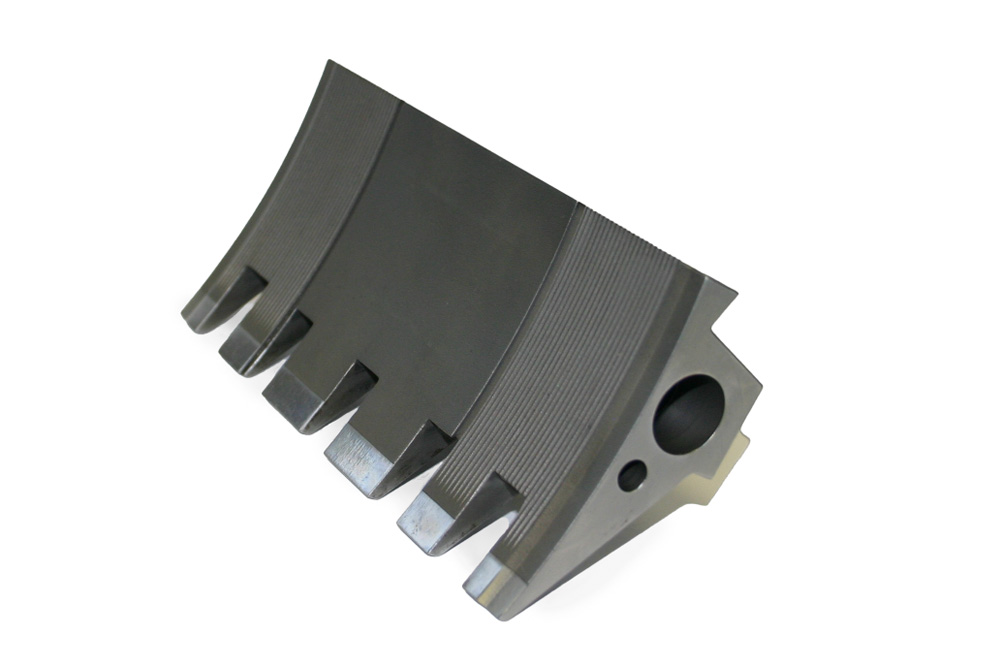

So why aren’t we all getting in on the act? Well, according to Iten, to be successful at such niche manufacturing, you have to be willing to make a certain level of investment. A secondhand maker that had been the subject of only an overhaul would probably produce more hassles than cigarettes. And buying the sorts of equipment sold by his company—rebuilt, as-new machines based on original OEM drawings—was not easy at the moment because of a number of factors, not the least of which was the lack of donor machines. In fact, Iten said he had plenty of inquiries at the moment but nothing to offer, so recently, he had been in discussions about how to overcome the current shortages of donor Molins Mk8 and Mk9 makers, especially their machine bases, since the mechanics and electronics of these machines were well known and could be reproduced fairly easily.

(Photo: gen_A)

Materials and Manpower

For start-ups, Iten recommends a standard industrial cigarette maker, such as the Mk8. For such machines, it was not difficult to find consumables and spare parts, many of which were off the shelf, and for others of which the original drawings were available so that they could be made by a proficient engineering company. Because of the Mk8’s ubiquity, even skilled operators were often available locally, but the machine’s most important advantage was that it produced a quality product.

But there are other problems with delivering rebuilt machinery, one of which comprises recent interruptions to deliveries of suitable raw materials. Not all materials were currently available, said Iten, so there were times when effort had to be expended finding substitutes, which increased costs and lead times. And these disruptions are occurring not only in respect of mechanical parts and materials. Electronic components, including PLC components, that used to be available immediately off the shelf are now subject to delivery times of six months or more. “The planning of a project has become really messy,” said Iten in an emailed reply. “It is simply not possible to keep a delivery time agreement these days.”

In fact, Iten described the delivery interruptions, which had started in 2020 with a lack of container availability and had become worse since May 2020, as “incredible.” Now, before a machine rebuilding project was started, it was necessary to have ordered all of the e-parts for the PLC control. A shortage of manpower was another factor—one that was causing some workshops to be operating under capacity.

Iten said he expected the current problems to last through 2022 and even expand. It was not possible, he added, to gauge what would happen during 2023, but it was likely that things would remain difficult.

Meanwhile, TMQS also helps niche tobacco manufacturers set up their operations. Schulz-Nemak said TMQS could rework machinery and set it up so as to operate easily and flexibly to meet a wide range of production needs. It could provide additional machinery, high-quality parts and assembly groups.

And when it came to setting up small operations, TMQS could combine forces with experts in different fields to create the optimum, cost-effective production lines.

The writer would like to thank Chris Crawley, global business development consultant to the tobacco industry, for his input on this piece.