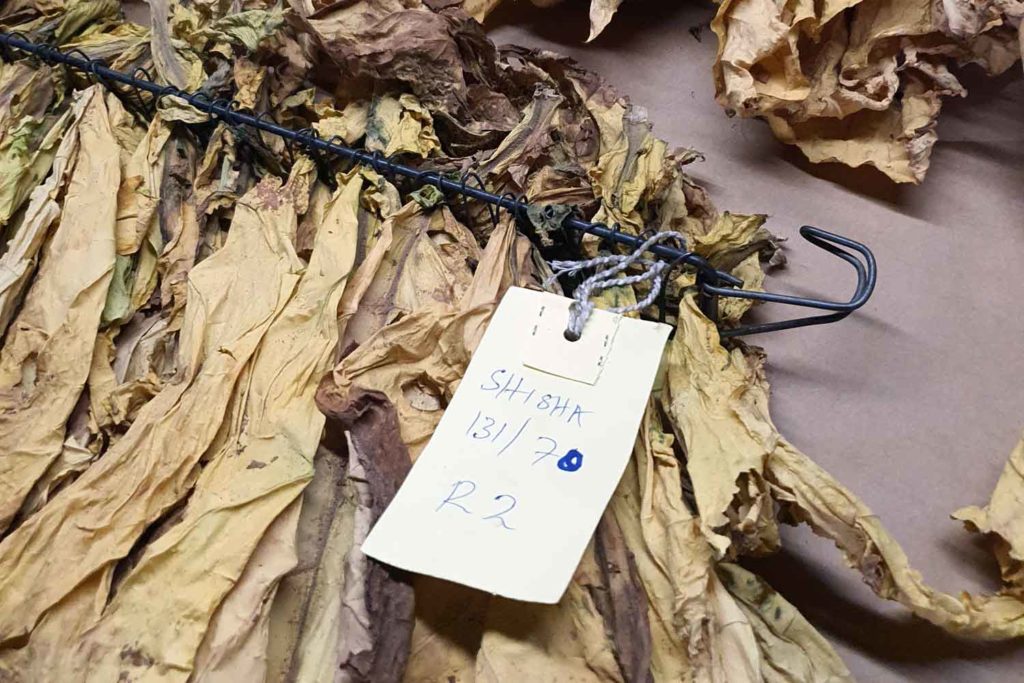

(Photo: Taco Tuinstra)

Zimbabwe’s minister of Agriculture, Anxious Jongwe Masuka, explains how the country will build a $5 billion tobacco industry by 2025.

By Taco Tuinstra

Following the resignation of Zimbabwe’s longtime president, Robert Mugabe, in late 2017, the new government invited private citizens to provide ideas on how to improve agriculture. Drawing on his extensive background in agriculture, policy and strategy, Anxious Jongwe Masuka wrote a letter in which he detailed the steps that he believed would help the nation achieve a prosperous, sustainable and competitive agricultural sector.

One of the issues he mentioned was tobacco, the country’s most important agricultural export by a wide margin. Zimbabwe has the potential to generate and retain much more value from its tobacco industry than it is getting now, Masuka argued in his missive, unaware that he would soon be put in charge of the sector.

“Then, when I was appointed a minister, President Emmerson Mnangagwa handed me back my letter and said, ‘I fully agree with what you have written here, and now please go ahead and implement it,’” recalls Masuka.

Tobacco Reporter caught up with Masuka at the Ministry of Agriculture in Harare to discuss the details of what is now known as the Tobacco Value Chain Transformation Plan.

Tobacco Reporter: Please briefly sketch the economic significance of tobacco to Zimbabwe. How much of the value created is retained domestically, and why does it fall short of its potential?

Anxious Jongwe Masuka: The context of the tobacco industry in Zimbabwe is exciting, since the first tobaccos were grown by missionary priests and presented at a show in 1895. Tobacco is one of [the] great successes for the country. By 1998, 1,500 large-scale white farmers produced a record 239 million kg. At the time, only a handful of small-scale Black farmers, less than 1,000, produced the crop. Following the land reform program from 2000 onward, the demography has dramatically shifted. A new record 260 million kg was produced in the 2019/2020 season, predominantly by smallholder farmers who constitute over 85 percent of the growers.

The tobacco crop annually supports up to 160,000 households, accounts for more than 50 percent of agricultural exports and contributes 25 percent to agriculture GDP.

Tobacco production is now a catalyst for accelerated rural development. Tobacco is grown predominantly by smallholder farmers, who constitute 85 percent of producers. Tobacco supports, directly and indirectly, 10 percent of Zimbabwe’s population (1.5 million).

Some 98 percent of tobacco is exported in a semi-processed form. However, according to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, only 12.5 percent of total exports is the net benefit after payment of external loan obligations by tobacco merchants.

Zimbabwe produces 6 percent of the world’s tobacco. The global tobacco market is estimated at US$850 billion, and 6 percent of the value translates to $51 billion of the global market value of tobacco. In 2020, Zimbabwe produced and exported over 200 million kg of tobacco worth only $991 million, so clearly there is scope for massive value retention in the country.

This is the basis for the Tobacco Transformation Plan, an idea I floated to the president in 2018 when I was still in the private sector and before being appointed minister in August 2020.

What are the Tobacco Transformation Plan’s main objectives?

From the mentioned statistics, it is clear that the industry must transform for value preservation and for sustainability. The Tobacco Value Chain Transformation Plan seeks to increase tobacco production to 300 million kg by 2025 and transform the value chain into a $5 billion industry through exports of tobacco value-added products. The broad objectives of the plan are to accelerate localization of tobacco funding; increase tobacco productivity and production from 210 million kg to 300 million kg; increase production of alternative crops and increase their contribution to farmers’ incomes; increase the level of tobacco value addition and beneficiation into cut rag and cigarettes; and ensure sustainability and traceability in the production of the crop.

Why is such a large share of cultivation currently funded by contractors? And how does the Tobacco Transformation Plan seek to remedy this situation?

Collateral, title deed-based financing collapsed in 2000, when all agricultural land became state land. By 2004, tobacco production had plummeted to 48 million kg from a high of 239 million kg. A dual marketing system was then introduced by government—a contract system was allowed, operating alongside the established auction system. Over the years, the contract system was refined to provide agronomic and farm infrastructure and equipment support in addition to inputs and working capital. Resultantly, and cumulatively, over 95 percent of production is currently funded through contract farming. This contract production financing model of tobacco requires that tobacco be prefinanced by offshore funding.

Local lending by local financial institutions for farming purposes is limited, particularly for small-scale farmers who do not meet the collateral requirements following the collapse of title-based lending in 2000.

The localization plan will involve government availing $60 million as seed finance to establish a revolving facility. The plan will operate alongside contract production of the crop. This will anchor the growth to 300 million kg.

How do you view the role of tobacco buyers in the future? Will they still be funding tobacco cultivation after the Tobacco Transformation Plan has been carried out?

Zimbabwe envisages growing the tobacco industry to a 300 million kg crop by 2025—an additional 90 million kg from the current average production of 210 million kg—so there is room for both contractors and local financing. The government is not replacing anyone in the current system, especially contractors and buyers. In fact, the exact opposite—we require more contractors and more localization of financing. We envisage that contractors can operate in both systems, whether the source of financing is offshore or is local, a contractor will be required alongside some direct lending to farmers.

According to some economists, one of the reasons smallholder tobacco growers have struggled to access funding in the past was lack of titles to their lands. What is the current situation in terms of property rights? Does the Tobacco Transformation Plan deal with this issue?

Those economists are misguided. Tobacco production has reached an all-time high in the current tenure system, post-land reform. All agricultural land is vested in the state, and for the right reasons, following the land reform program. Farmers got offer letters, and now securitized A1 and A2 permits and thereafter 99-year leases. It is in this context that tobacco production has grown through strong value chain or contract-growing support.

Government is currently seized with the legal reviews to make permits and leases more attractive to financiers, so issues of collateralization, transferability and valorization are being discussed.

It is also important, for emphasis, to highlight that the Tobacco Transformation Plan is an agronomic plan, not a land reform plan.

Are you confident that Zimbabwe can sell a 300 million kg crop even as global cigarette consumption stagnates?

Zimbabwe will achieve 300 million kg of production by 2025 through increased yields and reduced post-harvest losses. Zimbabwe produces flavor-style tobacco, currently marketed to 60 countries. This style of tobacco will continue to be in demand for the foreseeable future in these countries and beyond. We are also exploring new markets to replace lost markets. Tobacco smoking is by choice, and we think many will continue to choose to smoke Zimbabwean tobacco.

Tobacco cultivation has environmental impacts, such as deforestation. What measures are in place to protect the environment as the tobacco industry expands?

The targeted increase in volume to 300 million kg is not from area increase but from post-harvest loss reduction and yield increase. There is, therefore, no envisaged additional deforestation from the increased production. However, the government has created a law for tobacco farmers, so there is an afforestation levy administered by the Ministry of Environment, Climate, Tourism and Hospitality to reverse deforestation caused by the tobacco sector. The industry has a sustainable forestry association, which plants tens of thousands of eucalyptus trees annually.

Alongside this, research and development has also led to more efficient curing systems, reducing wood and coal usage from 10 kg [of tobacco] to 1 kg [of] tobacco and 6 kg [of tobacco] to 1 kg [of] tobacco, respectively, to almost 1 to 1 for coal to tobacco in current continuous curing systems. Biofuels are also promising fuel alternatives to curtail deforestation.

All contractors have now signed the sustainability code, and traceability has been heightened to ensure farmers use alternative curing fuel. Growers are also encouraged to plant 1 hectare of trees for every 7 hectares of tobacco, and seedlings are readily available.

This cocktail of measures will reduce the industry’s environmental footprint.

Please comment on the Tobacco Transformation Plan’s goal to promote alternative crops. What crops are you targeting, and how do they compare to tobacco in terms of earnings for the farmers and economic contributions to the country?

Tobacco is already grown in rotation with various crops, for example, maize, and there is also livestock grazing on rotation grass. We need to enhance these and look for alternative crops, for example, industrial hemp and cannabis. The objective is to complement tobacco, not to replace it.

In 2018, Zimbabwe legalized cannabis for medical and industrial use, with some predicting earnings on par with those of gold. How has the cannabis industry developed since 2018? What have been the major lessons of Zimbabwe’s experience with this crop to date, and what are your expectations for its future?

Zimbabwe has just legalized the production of cannabis and has issued licenses to 60 growing units. This industry is at a developmental stage, and we expect rapid growth.

The Tobacco Transformation Plan seeks the beneficiation of tobacco by encouraging value-added production. What progress has been made in this area to date? Please comment on the reports about local cigarette factories planned by Cut Rag Processors and Iranian Tobacco Co.

The environment for investment has seen much improvement, and we expect investors to take advantage of this, including Cut Rag Processors, the Iranians and many others.

What do you consider to be the greatest challenges to achieving the objectives of the Tobacco Transformation Plan? And how are you addressing those challenges?

By far the greatest threat is from the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which seeks to eliminate tobacco smoking. This will have tragic consequences for tobacco-dependent African countries such as Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Then there are issues of adherence to sustainability and traceability and ensuring growers’ viability.

More discerning markets want their tobacco to be produced ethically and sustainably. These are legitimate concerns. We are taking this on board and going to every length to show we are producing this tobacco in a sustainable manner, eliminating child labor, traceability, harmful substances, etc.

Ultimately, growth in this industry will depend on grower viability. Due to the war between Russia and Ukraine—two major sources of raw materials for fertilizer production—and disruptions to the global supply chain, among other factors, the cost of production for tobacco [has] increased by 30 [percent] to 40 percent. Without a corresponding increase in the price, this means that farmers are squeezed and will therefore have to produce the crop more efficiently.

We must highlight also that success of the Tobacco Transformation Plan depends on a whole-of-industry approach. The government has created a tobacco working group involving all stakeholders. Every quarter, representatives of tobacco growers, labor unions, buyers, bankers and regulators meet to discuss progress of the Tobacco Transformation Plan, and we look forward to accelerating its implementation.

Have the various stakeholders generally been receptive to the Tobacco Transformation Plan?

They have been extremely receptive. The Tobacco Transformation Plan was long overdue.