Cheryl K. Olson is a California-based public health researcher who specializes in behavioral health issues and consults on tobacco product behaviors via McKinney Regulatory Science Advisors. She spent 15 years on the faculty of Harvard Medical School. In this section we feature a selection of Olson’s contributions to Tobacco Reporter

Slim Chances

Harm reduction, smoking cessation and weight

Warm Reception?

How heated tobacco might change the US

Playing with Numbers

How research methods distort nicotine effects and risks

Quitting Camel Country

Dokha, shisha, vapes: THR in the Middle East region

Real-World Quitting

What we know, and don’t, about how people stop smoking

Taking Stock

Where are we with ESG?

Putting Faith in Cessation

The role of religion in encouraging smoking cessation

A Widening Gap

Tobacco harm reduction for people with mental health needs

Surprising Successes

The uncelebrated triumphs of tobacco harm reduction

Correcting The Record

Targeting tobacco risk communications

Cheryl Olson

Read a selection of work from Tobacco Reporter’s special contributor Cheryl Olson.

Why Don’t They Just Stop?

Utopian visions and unintended consequences

Staking a Claim?

Rethinking the modified-risk tobacco products approval process.

Fighting the Dip Mentality

What will it take for women who smoke to consider smokeless?

Where’s the Parade?

Record-low youth smoking rates get no respect.

A Teaching Moment

Nicotine’s lessons for cannabis regulation

Science-based Regulation?

Politics and data in tobacco harm reduction

Reality Check

To what extent do flavor bans achieve their stated objectives?

Choosing Wisely

Are choices key to successful switching?

‘Forgotten’ Smokers

A GTNF 20222 panel discussion

The Dilemma of Diversification

The industry’s move into pharma may be positive for public health.

Listening to Nicotine Users

A GTNF panel will put “forgotten smokers” in the spotlight.

Not “A Solved Problem”

Acknowledging reality at the E-Cigarette Summit

Not a Bot

Consumer advocates are for real.

White Coats, Fuzzy Facts?

Educating physicians on nicotine and the risk continuum.

Unlikely Bedfellows

How free-flowing data streams can help advance public health goals for nicotine products.

Watch Your Mouth

What the industry can’t (and could) say about harm reduction

Appropriate for the Protection of Health?

The FDA’s focus on nicotine is coming at the expense of true harm reduction.

Who D’Ya Think You Are?

Your business from the regulators’ perspectives

Acting Unnaturally

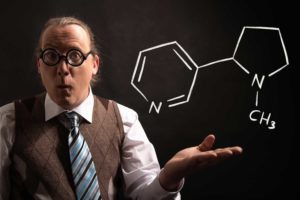

Synthetic versus tobacco-derived nicotine

Crossing the Divide

When scientists work for a tobacco company

Taming the Moral Panic

A recent landmark article offers a rare balanced look at vaping in the U.S.

The Credibility Gap

What industry scientists wish they could say to public health researchers about their work.

Filling the Gaps

The FDA gifted you a PMTA deficiency letter … what’s your strategy?

“Grandfathered” Attitudes

Past tobacco industry behavior affects how U.S. regulators treat you today.

Gold Nuggets

Willie McKinney and Cheryl Olson share their insights into the FDA’s final PMTA rule

Perception and Intention Studies

The most confusing part of an FDA application explained